Sacred Seeds: A Journey to the Past to Chart a New Future – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2020

Sacred Seeds: A Journey to the Past to Chart a New Future

By Michaela Jones

When a longtime mentor and friend asked Taylor Keen what he was doing to protect his corn, he could only reply: “Do what?”

For Keen, a member of the Omaha Tribe and Cherokee Nation, that question was the genesis of an idea that soon turned into a passion that took root in his own backyard and has since grown far beyond.

Referring to historic varieties of tribal corn, Keen’s mentor, Deward Walker, a professor emeritus of anthropology at Colorado University, Boulder, warned him about the potential dangers from large agrochemical companies. If any of the remaining pre-colonial species of Native American seeds were to cross-pollinate with corporately owned seeds, Walker explained, major agricultural companies could try to patent the product, claiming the offspring as their own.

That conversation, which took place 15 years ago, ignited Keen’s mission to help bring the rich history and tradition of Indigenous and heirloom seeds back to his native Omaha and Cherokee people, and away from industrial farming practices.

Though Keen had little knowledge of gardening or growing food at the time, he knew it was “terribly important,” and a race against the clock to preserve what was left of these rare seeds.

“We got started, and I had a couple of classes come help me, and they helped define what the work was,” said Keen, an instructor at Creighton University’s Heider College of Business. He is also a member of the Plains Indian Museum Advisory Board. “We began to research and explore further, and really began to uncover this legacy.”

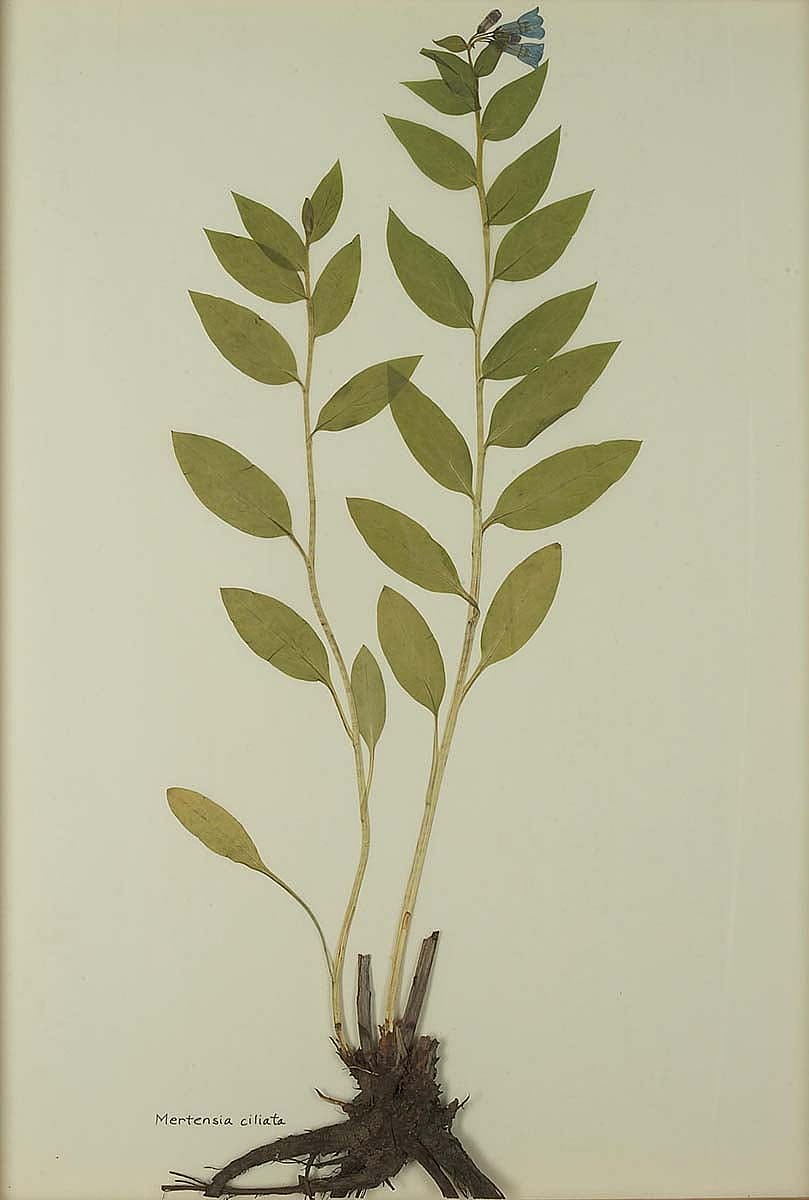

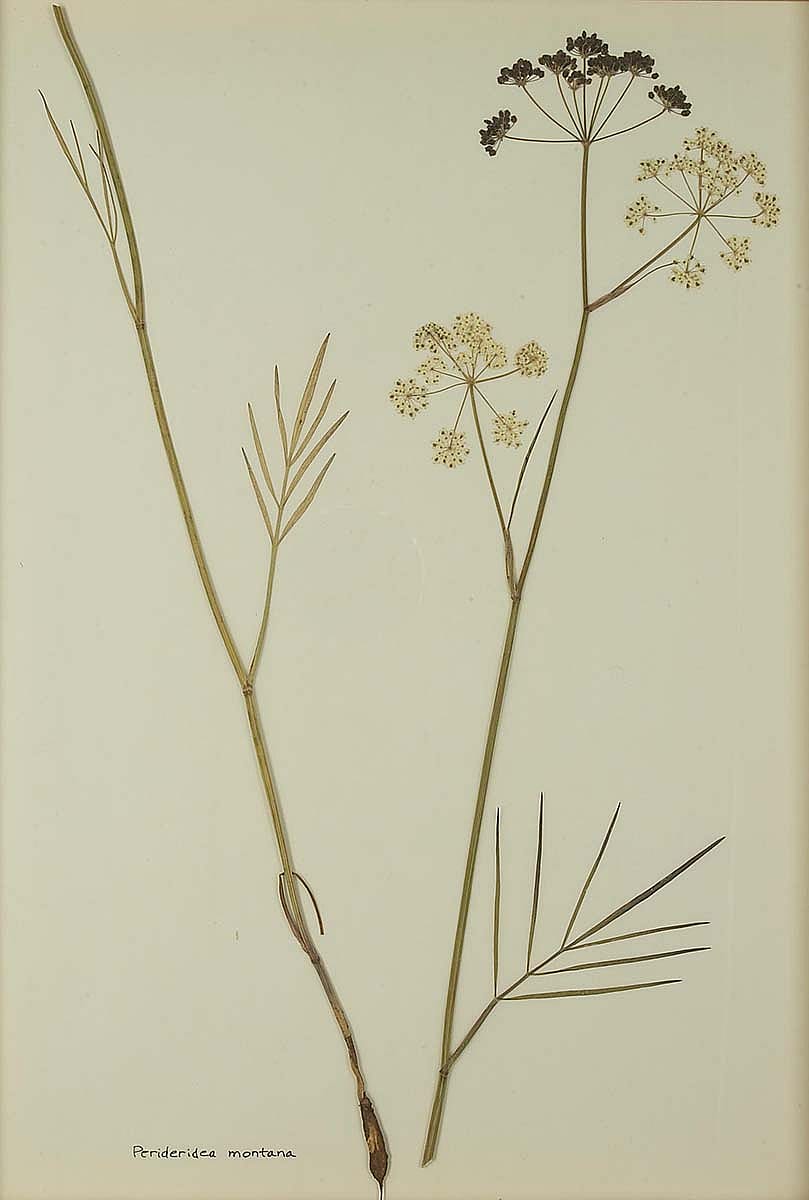

Plains Indians have used a variety of edible plants for food and medicine. Pressed plant specimens from the Plains Indian Museum collection.

In 2014, Keen founded Sacred Seed, a nonprofit that propagates tribal seed sovereignty and promotes sacred geography, with a focus on Indigenous seeds of the upper Missouri River tribes.

That movement with humble backyard beginnings has exploded with plots dotting the Omaha, Nebraska, area, promoting local, traditional, and sustainable agriculture to offer healthy food to those in surrounding communities.

Through a partnership with The Land Institute in Salina, Kansas, growers are working with seeds donated by Keen to grow crops like Cherokee White Flour corn, Scarlet Runner beans, Lakota squash, Arikara sunflowers, and others.

But six years ago, Keen began the project by creating small plots in the backyard of his previous home. He planted the Three Sisters, a traditional trio of corn, beans, and squash cultivated by a range of Indigenous People. He also added a commonly found fourth sister, sunflowers, to the mix.

When planted together, these Four Sisters do much more than provide a fruitful harvest—they thrive together, each serving an important, individualized role, Keen explained. Sunflowers protect against the strong Nebraska winds and divert birds from the corn. Corn acts as a trellis for beans and takes nitrogen out of the ground. Beans return nitrogen to the soil, and squash fends off raccoons and other pests.

Before long, what was once Keen’s backyard soon became home to dense, vibrant vegetation and a thick forest of golden sunflowers that nearly camouflaged the roof of his home.

Though Sacred Seed’s reach has expanded significantly in recent years, Keen has no plans of slowing down.

Between 1858 and 1870, he explained, many tribes were nearly or entirely economically self-reliant, just through the sale of excess corn.

“That just blew my mind,” Keen said. “Because we have, in our past, these models of how we could take care of ourselves.”

His hope is that, one day, Omaha tribal members will be fully economically self-sufficient by growing corn without harsh pesticides or fertilizers on land the tribes lease to farmers.

“Will it ever happen? I don’t know,” he said. “Can I see the dream? Yes.”

While economic sustainability is the ultimate goal, it’s only one of the benefits of preserving Indigenous crops and reviving the traditional farming methods of his ancestors. Long before European settlers plowed the Great Plains, corn was a staple in the diet of several Native American tribes.

“Many Native Americans are lactose intolerant,” said Rebecca West, curator of the Plains Indian Museum. “These food and dietary changes have caused issues and have had lasting negative effects on their health.”

Keen said that “in the bigger picture of things, I understand what Monsanto and Syngenta and some of these other big seed companies are trying to do. They’re trying to feed the world, and that’s a terribly important thing.”

But promoting seed diversity and preserving traditional farming methods are important goals too, he said.

“There are many people doing all these things—tribal peoples who are reconnecting with their seed varieties and their ancient agricultural Indigenous lifeways, and we’re all trying to make the world a better place,” he said.

Time and time again, Keen has found his work paying off in unexpected ways.

A few years ago, he went for a run along the winding Shoshone River in Cody, Wyoming, after being struck by the words of Philip J. Deloria, the only tenured Native American professor at Harvard University. Deloria had wondered when we will start listening to the plants and animals again.

Completing his run, and continuing to mull over those words, Keen stopped by the river, where he offered a prayer and said: “If ever the plants and animals need to tell me something, may I be a sturdy enough vessel for that honorable task.”

“I didn’t realize what a powerful prayer that was,” he said.

Later that day, Keen headed back to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West to meet up with West, a longtime friend and colleague.

West asked Keen if he’d be interested in looking at some unidentified objects downstairs.

Enthusiastic to do so, they eyed the carefully sealed tribal artifacts. Slowly looking through the box, he unveiled an object, revealing a perfectly preserved ear of corn with its crown painted blue and decorated with thin lines leading toward the husk.

“I immediately realized that we had found the Omaha Mother Corn in the collection at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West,” Keen said.

This sacred artifact, believed to have been lost to the tribe for more than 130 years, brought bounty and fertility to the Omahas, and was traditionally used to bless newborn infants.

“We got it moved to the sacred collection, and [West] gave me time so I could pray, and I talked to the collection of the objects. Those bundles—we viewed them as people,” he said.

“It was a really moving experience,” West said. It’s moments like these that show corn is not only representative of food, but also spiritual sustenance.

With the beginning of summer, Keen always looks toward his roots and the ways of his ancestors as he prepares for each new planting season with the Four Sisters.

“We’ll watch them grow and take care of them and protect them from the wind, the rain, and the hail,” he said. “It’s always, always a journey.”

About the author

Cody native Michaela Jones is the communications/social media specialist at Northwest College in Powell, Wyoming. In her free time, she enjoys reading, writing, cooking, and paddle boarding.

Post 291

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.