Lies and Legends of Montana Bill, Part 1 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2018

Lies and Legends of Montana Bill, Part 1

By Tom F. Cunningham

Wild West Echoes in Glasgow

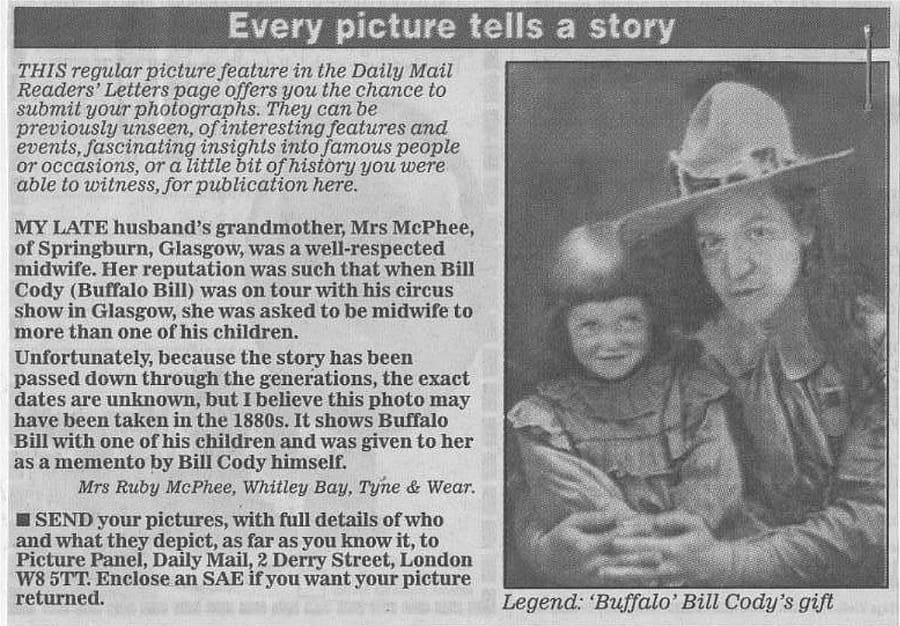

Of all the myriad objects in the collections of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, by no means the most valuable—but certainly amongst the most perplexing—is an undated newspaper cutting. Included in the London Daily Mail‘s “Every Picture Tells a Story” feature, the clipping is believed to be from the early 2000s.

The contributor on this occasion, Mrs. Ruby McPhee, of Whitley Bay, Tyne & Wear in England, provides the commentary:

My late husband’s mother, Mrs. McPhee, of Springburn, Glasgow, was a well-respected midwife. Her reputation was such that when Bill Cody (Buffalo Bill) was on tour with his circus show in Glasgow, she was asked to be midwife to more than one of his children.

Unfortunately, because the story has been passed down through the generations, the exact dates are unknown, but I believe this photo may have been taken in the 1880s. It shows Buffalo Bill with one of his children and was given to her as a memento by Bill Cody himself.

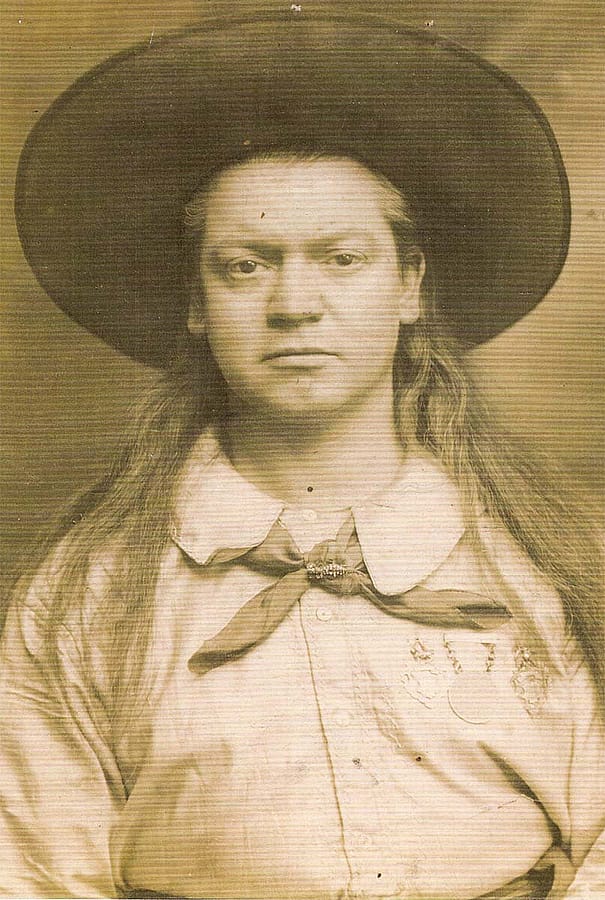

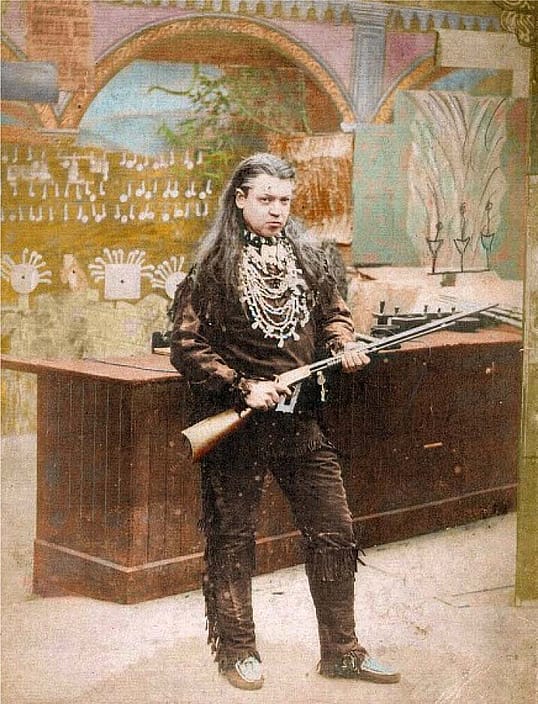

My attempts to trace Mrs. McPhee unfortunately failed; I would have welcomed the opportunity to ask her how many of Buffalo Bill’s children she supposed had been born in Glasgow. Of the two figures in the photograph, one is an unidentified little girl. The other is a very long-haired man in what appears to be one interpretation of frontier garb, who may or may not have been her father. What can be stated as a matter of certainty is that—while he has the definite look of James Cagney about him—anyone with even an approximate notion of what Colonel Cody looked like could immediately tell you: It’s not him.

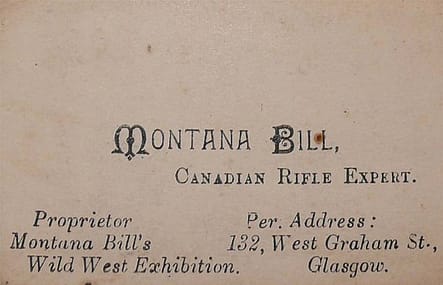

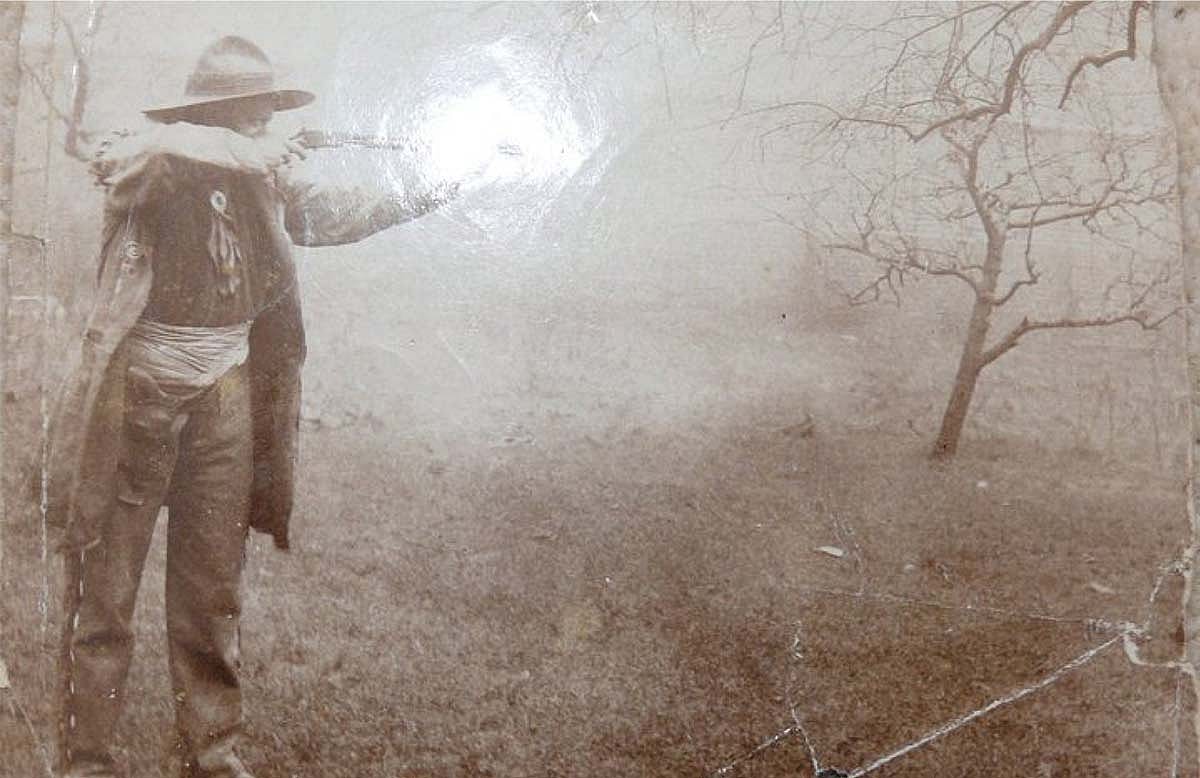

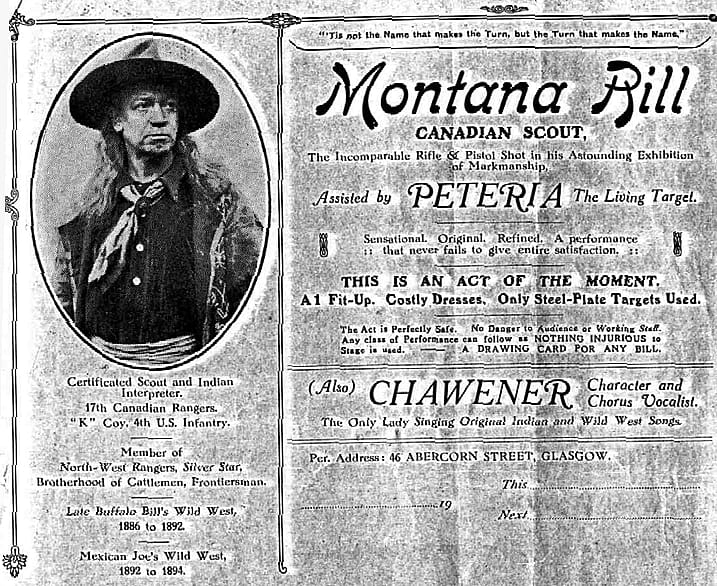

The gentleman in question can positively be identified as Robert Bailey Robeson, otherwise known as “Montana Bill,” a U.S. citizen who lived in Glasgow roughly from the last years of the nineteenth century until his abrupt departure in 1919. During this sojourn, he achieved a modest notoriety with a trick-shooting act. He was also a cowboy actor, and there is evidence that, on occasion, he even managed to mobilize a small-scale Wild West show of his own. According to one family tradition, he used to ride his horse down the Garscube Road, just north of the Glasgow city center.

When, how, and why he first came to Scotland is one of the few remaining loose ends. However, one of the very first documented encounters with “‘Montana Bill,’ the Indian sharpshooter” is recorded in the Dundee Courier & Argus, January 4, 1897, in connection with the New Year Fair at the Greenmarket in Dundee:

“Montana Bill” was quite a picturesque object. He wore a red shirt trimmed with barbaric ornaments, and his long, dark locks hung down his back like a school girl. He had on his war paint, and he showed some good shooting with a Colt rifle. He finished his target practice by firing at a pipe head set on the head of the lady who acted as his marker—the William Tell feat modernized.

I had a quiet talk with Bill…He had an Indian cast of features, and he informed me he was what was called a “half-breed.” His father was a French Canadian, and his mother a squaw of the famous Sioux tribe of American Indians. He was born in the “Wild West,” and learned to shoot when a child to save his life. Six or seven years ago he came over with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Since then he had performed in music halls in England and Scotland, and fulfilled engagements at from £12 [$16.78] to £20 [$28] a week. He seemed an intelligent, good-natured fellow, and I could not help thinking as I shook hands at parting what strange experiences some men have who are thrown on the world to live by their wits.

As any family historian will tell you, ancestors fall into a broad spectrum between those who cling to immortality and those who choose to embrace oblivion. Fortunately for his living descendants, several of whom are actively engaged in decoding the truth about their remarkable patriarch, Montana Bill lies at the top end of the range. His legacy consists of an impressive collection of photographs, press cuttings, letters, and various other documents including a brief but arresting hand-written manuscript. In it, he summarized his life of unbroken adventure and elaborated on the brief potted biography cited above.

Life and Adventures of Montana Bill

Montana Bill’s brief memoir is preceded by a short introduction opening with the formula ‘Ladies & Gentlemen,’ giving the clear impression that it was originally intended as a viva voce [in person] address. It continues, with the characteristically eccentric spelling, grammar, and syntax all his own:

Dealing first with my parentage my father was a French canadian who served both Canadian and United States government in the capacity of Scout and Surveyor & was one of the few survivors of the Fort McKinnon macacre [sic] of 1838. My Mother was a Oklala [sic] Sioux belonging to the pine ridge agency. A special word…may be given in reference to my mother her name was Ne-Oska-Letta, daughter of Chief Rain-in-the-Face fighting warrior of the Sioux nation who was…in the battle of the Bad-Lands in 1890. I was born in an Indian Teppa (Wigwam) on the Red rock river of the North two miles outside of Winnipeg, Manitoba Canada, in January 1855.

It is, of course, entirely typical of the man and of his sort that his maternal grandfather was not some obscure Indian of whom no historical record survives, but the historical chief who was long reputed as the slayer of Custer. It might also be noted in passing that the name which he attributes to his mother is not recognizably Lakota. One might also go so far as to ask what an Oglala band was doing so far north of its accustomed range.

Montana Bill was raised amongst his mother’s people, and his was the classic Indian boyhood. He began to exhibit a prodigious talent with firearms, for which he received the tribal name of Short Rifle, and participated in his first battle at the age of nine. The years which followed were packed with all the familiar incidents of war and hunting:

- The manuscripts are silent, but his press releases make occasional references to a role as an army scout in repelling the Fenian (Irish Republican Brotherhood) incursions into Canada. This is difficult to reconcile with other details which Montana Bill furnishes concerning his early life. Besides, since this particular episode took place in the years immediately following the American Civil War, it seems very doubtful, even if we provisionally accept 1855 as the year of his birth. He would have been only 10 years old.

- Short Rifle, or Montana Bill, as he came to be better known, was eighteen years of age before he ever saw a white woman. His first introduction to civilization came in 1873, when he was engaged as a scout in the United States Army. He supposedly had a particularly heroic role in the Massacre of Glendive, with an epic forty-mile ride for reinforcements, at the end of which, with commendable theatrical timing, his horse dropped dead under him. Further particulars concerning this fight, even in the Internet age, are extremely hard to find.

- In the Battle of the Little Bighorn, otherwise known as Custer’s Last Stand, a bullet passed through Montana Bill’s left leg, killing his horse and incapacitating him for three months. He gives the date of the battle as June 26, 1876, but, unfortunately, neglects to tell us which side he was on.

- In the spring of 1879, Montana Bill was back with the Indians and was again wounded. In the course of an encounter with a band of forty horse thieves, he received a knife thrust to his left wrist while parrying a blow to his heart.

- In the fall of the same year, in the war against the Crows, a spear thrust grazed his right temple, “the scar of which I will carry to the grave.” A superscripted insertion to the text states that “This lasted over 6 hours and was one of the Bloodiest Battles ever recorded in Indian History.” The same incident is referred to in an undated newspaper advert as “The Crow Uprising September 18, 1879.” This is seriously problematic, though, as this event, in the historical reality, was a brief and farcical affair. It culminated in a skirmish on Saturday, November 5, 1887, the very day on which, as we shall see, Montana Bill was supposedly in Birmingham, England, with Buffalo Bill.

- From 1879 until 1883, Montana Bill returned to the service of the United States government, as a scout, guide, and hunter, supplying the military posts with fresh meat in the form of “deer, antelope, bear, & buffalo.” From 1883 until 1885, he assisted the Canadian government in suppressing his fellow mixed-race foes during the Riel Rebellion.

In the course of these epic endeavours, Montana Bill inevitably endured further disfigurement. He survived a rattlesnake bite, and on another occasion, a wild horse that he was attempting to subdue bit off the top of the first finger of his left hand. The manuscript account of this mishap includes the phrase “as no doubt a number of you would notice,” a further indication that it was intended to be presented to an audience actually present before him. Like the spear wounds on the hands and side of the risen Christ, his various scars and injuries could scarcely have been counterfeited; as we shall see, they were real enough.

Joining Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

Having thus firmly established his frontier credentials, the next logical step was to sign up with Buffalo Bill:

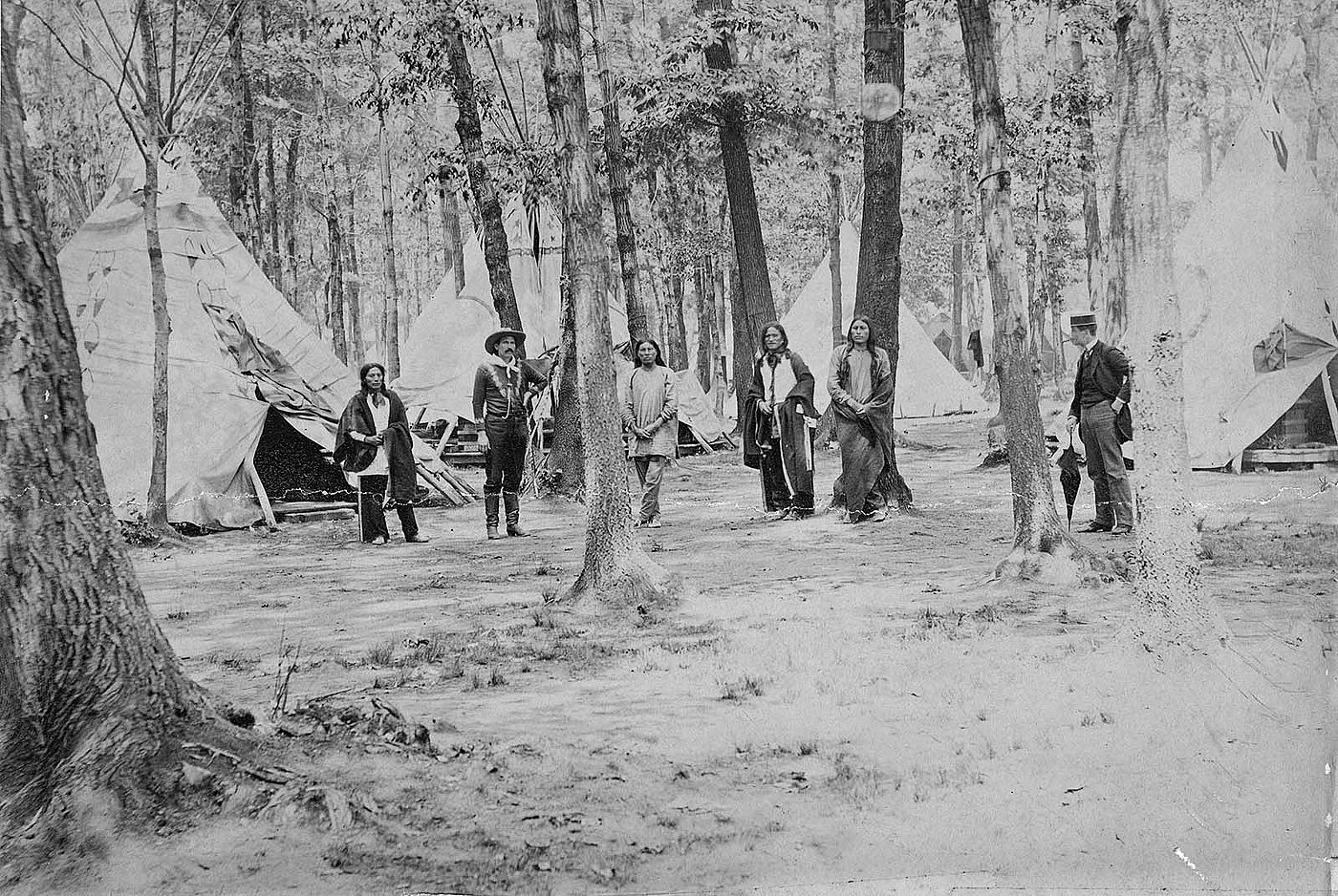

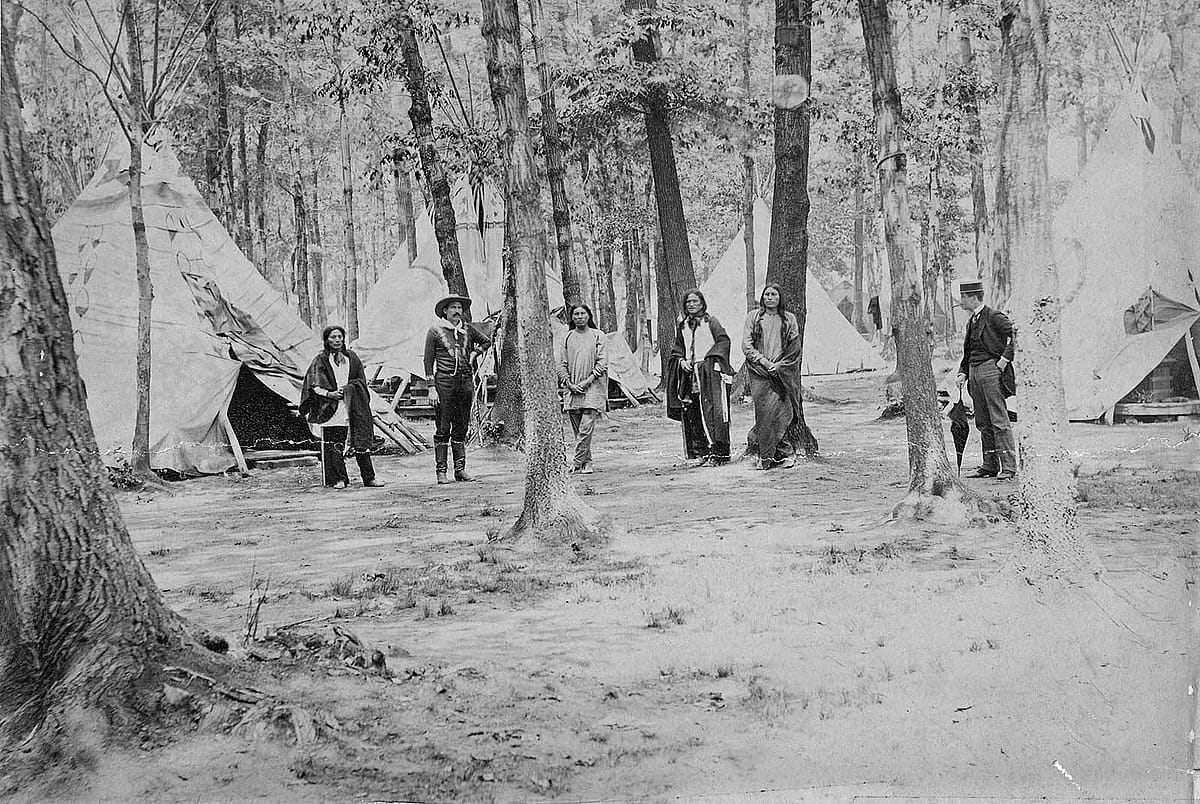

In the spring of 1886 I was approached by the representatives of Buffalo’s [sic] Bill’s exhibition to join him in his Wild West show at Erostina Staten Island. I was specially engaged by my old pard & comrade as interpreter to the different tribes of Indians…

These included “some of the most warlike tribes of them days…Apatches, Commanchies, Crows, Pawnnes, Souixs, & Shayannes.” That such a diverse array of western tribes was ever represented in Buffalo Bill’s show is hard to reconcile with the historical record. Even if they were, how exactly Montana Bill found the time or opportunity to acquire linguistic proficiency in all their languages is an absolute mystery.

During this phase of his career, Lillian Smith and Doc Carver were but two of the legendary sharpshooters whom he claims to have met and (naturally), without exception, defeated.

Montana Bill went to London with Buffalo Bill in the spring of 1887 and, of course, performed his shooting act before Queen Victoria, remaining with the show until October 1892. At that time, he wrote, “Not wishing to return to America I joined the renowned Mexican Joe’s Wild West, again travelling the Brittish Isles remaining with him untill his failure at Barnsley in March 1894.”

In common with such other ostensible luminaries as Chief William Red Fox and Frank T. “Hidalgo” Hopkins, no supporting record of Montana Bill’s participation in the Wild West has yet been found.

However, the statement concerning Mexican Joe’s financial failure at Barnsley during March 1894 is actually correct. This, taken together with a wealth of other details, demand the conclusion that Robert Bailey Robeson—Montana Bill—quite probably was a member of Mexican Joe’s troupe during the period in question. Even the name of Montana Bill’s “Lakota” mother, Neoskeleata, was a Mexican Joe influence. It had previously been the nom de plume of one of the “Apache” women in his show—more prosaically, the Winnebago, Nana Jefferson.

Robert Bailey Robeson, the truth

Amongst Montana Bill’s effects is a birth certificate. It notes that the as-yet-unnamed male child of C.A. Robeson, a miner, originally from Ohio, and Fanny M. Bailey, birthplace New York, was born on January 1, 1870, in New York City. Since Robeson and Bailey are otherwise established as Robert’s parents, and it is known from other evidence that he was their only child, this is unquestionably the birth certificate of Robert Bailey Robeson.

“Montana Bill,” or “Manhattan Bob” as he might have been more appropriately called, was therefore fifteen years younger than he claimed to be—far too young to have participated in the various frontier incidents in which he was supposed to have played a decisive part.

Certainly, such a dramatic conclusion should be reached only on the most compelling of evidence. A so-called smoking gun does exist, however, in the form of an 1884 entry for “Robeson, Robert B.” in the Register of Enlistments of Apprentices in the United States Navy to serve until they shall arrive at the age of twenty-one years.

This confirms his date of birth as January 1, 1870, when, so we have been given to understand, he was already an adolescent Sioux warrior! He had enlisted on January 25, 1884, when, so his legion of admirers was led to believe, he was on a government assignment in the wilds of Canada.

According to the register, he was 5 ft. 2 in. in height; his hair and eyes were brown; and his complexion was fair. We are borne beyond the realms of simple coincidence by the entry under “Permanent Marks or Scars,” where there is noted “Scar above rt eye. Tip of index finger l. hand gone.” How exactly these wounds had been acquired, the Registrar neglected to determine. If ever a Crow spear or a wild horse bore any share of the blame, though, the record remains silent on the matter.

Young Robert probably saw the Wild West in New York as a spectator, though the inessential detail of Canada intrudes into so many contexts that one might suspect that a genuine Canadian sojourn may have been involved.

In Part 2 of “The lies and legends of Montana Bill” (find it here), Tom Cunningham continues his tale of Montana Bill, focusing on Bill’s professional and personal life.

About the author

For the last two decades and more, Tom Cunningham has pursued an intensive study of Native American history with particular emphasis on connections with Scotland. He is the author of The Diamond’s Ace—Scotland and the Native Americans, and Your Fathers the Ghosts—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Scotland, with much of his research conducted at the Center of the West.

Post 292

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.