Lies and Legends of Montana Bill, Part 2 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall/Winter 2018

Lies and Legends of Montana Bill, Part 2

By Tom F. Cunningham

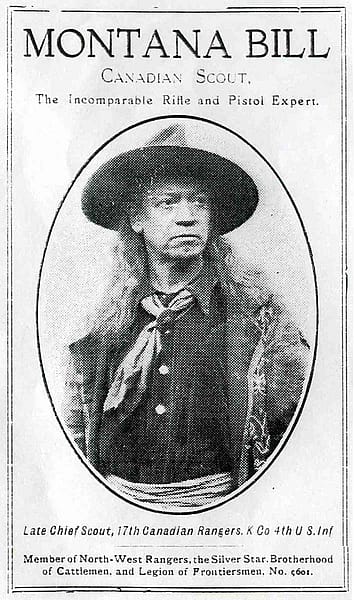

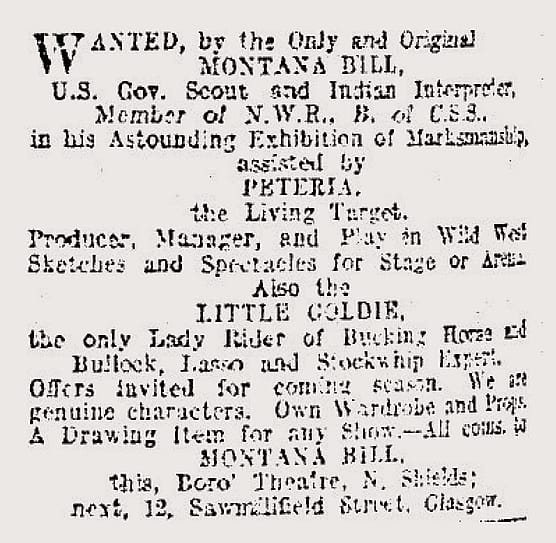

Characters abound in the West, and in the last installment of Points West Online, author and historian Tom F. Cunningham introduced one Montana Bill. A contemporary of William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, he claimed to have been part of Cody’s Wild West extravaganza, even calling himself Buffalo Bill’s “right hand man” in numerous adventures. However, as Cunningham learned, there appears to be no supporting record to indicate that he was ever in the show. (At one time, he even had his own little Wild West show.)

But that’s not the only glib fib in the saga of Montana Bill, as Cunningham discovered when he attempted to sort through the multitude of tall tales and a gnarled family tree. Hang on to your hats!

Mom and Dad

A further element of truth [in the Robeson family drama] not to be neglected emerges from the revelation that Robert Bailey Robeson’s, i.e. Montana Bill’s, father, Charles A. Robeson, was indeed a minor frontier figure. Congressional papers place him in California, in the vicinity of Humboldt Bay, in the wake of the 1849 gold rush. Official correspondence dated September 9, 1851, complete with the (sometimes insensitive) vernacular of the day, states:

Mr. Charles A. Robeson, with his squaw wife, visited camp to-day at the request of the agent. This gentleman has recently settled upon, and is now opening up, a portion of land in this neighborhood, and to preserve friendly relations with the Indians, has married (Indian fashion) the daughter of a chief of one of the tribes. Through his squaw he has obtained a slight knowledge of the languages spoken on this river.

Charles therefore considerably assisted the federal government in the role of interpreter and cultural intermediary. A further aspect of his duties can be described as that of land surveyor. Certain key elements of the legend, including his union with the daughter of an Indian chief, were authentic, though transposed by the younger Robeson from California to Montana. For the patriarch of an obscure Californian rancheria, he substituted Rain-in-the-Face of the Sioux.

In a subsequent and less creditable chapter of Charles’s career, he hit the headlines from coast to coast during the early 1870s for fraudulently selling shares in an Idaho gold mine (recall that on son Robert’s 1870 birth certificate, Charles was a miner) as imaginary as was his son’s subsequent close association with Buffalo Bill.

Montana Bill in Scotland

Montana Bill was twice married in Scotland, and he had his particulars listed as father on the birth certificates of twelve children by three different women. It’s probably safe to say that he therefore made a sizeable impression upon the Registers of Birth, Death, and Marriage.

When Robert Bailey Robeson, traveling showman (bachelor), married Agnes Wilson in Glasgow on October 4, 1897, both parties gave their usual residence as the Show Ground, Bonnybridge. He correctly gave his age as 27 years and identified his parents as Charles Robeson, government surveyor (deceased) and Fanny Robeson Bailey. He gave no intimation of his mother’s alleged Native American origins.

Robert and Agnes then had two children—a daughter, Fanny Bailey Robeson, born 1897, and a son, Robert Edward Robeson, born 1899, who survived for only a matter of hours.

Agnes and little Fanny quickly fade from the picture, although almost certainly Robert and Agnes never divorced. By 1900 at the latest, Robert had taken up with Alice Ann Harrold (1880–1935), born to Irish parents in Glossop, Derbyshire, UK. She was his leading lady for many years, bearing him nine or possibly ten children.

Robert is also known from the 1911 census, in which he gave his age as 56 and his place of birth as Canada. Both particulars match with the manuscript version of his life.

Glory days of Montana

Montana Bill’s glory days came around the middle of the second decade of the 1900s. By this time, the fantasy version of his life was in full swing, and sons Andrew, born 1912, and George, born 1915, were both given the middle name of Montana. The same accolade was bestowed on granddaughter Edna Montana Rennie, born 1935.

During those years, Montana Bill mostly supported his ever-growing brood by doing the rounds of the fairgrounds, theatres, and music halls with his ever-popular trick-shooting act.

The Perthshire Advertiser was entirely typical in its uncritical acceptance of Montana Bill’s claim to have been “the noted Buffalo Bill’s right hand man in many wild adventures.”

On one occasion, Montana Bill shared the bill at the Dalkeith Carnival from December 23 to January 6 (year unknown), as:

Engaged at Enormous Expense for the remainder of the Carnival,

YOUNG CODY

(Son of the renowned Buffallo Bill),

Who will give a Marvellous Display of Lasso-Throwing.

It must certainly have made for an interesting family reunion!

Showdown in Blackpool

During this time, Montana Bill’s star had never shone brighter, but it was about to be extinguished as the truth followed on his trail like a nemesis. On July 3, 1916, he and a confederate were fined six shillings apiece by the magistrates in the Lancashire seaside resort of Blackpool on the northwest coast of England for causing an obstruction on Central Parade [i.e. promenade]. It was hardly a disaster in itself but proved to be the prelude to catastrophe.

The veteran showman had appeared in a Legion of Frontiersman uniform complete with medal ribbons which attracted considerable suspicion. When interviewed, Montana Bill reeled off a tissue of lies, of honours won in military campaigns over four different continents:

Captain Moffat, Assistant Provost Marshall, said prisoner told him he was entitled to wear the seven medal ribbons produced. One of these was for the Canadian rebellion in 1866; one was for another Canadian rebellion; a third was a D.S.O., which should have been first; the fourth the Queen’s South African Medal; the fifth a yeomanry long-service medal; the sixth a French medal for life-saving; and a seventh the Antarctic medal.

The accused told him they were Canadian awards, and that the D.S.O. ribbon was the Canadian D.C.M. The facts had been submitted to the War Office, who declared that prisoner’s statements were untrue.

The prisoner forlornly confessed that “he wore the ribbons more for show than anything else.” On Friday, November 3, 1916, he was committed to three months’ imprisonment and collapsed on hearing the sentence.

Probably the oddest aspect of the whole affair is that he appears to have been charged under the name of Montana Bill and that the papers described him as “an elderly man,” aged 62. He was in fact 46.

Montana Bill was quoted as lamenting that “the prosecution would ruin him if it became known” and this melancholy prognosis proved to be correct. The pages of his engagement book are distinctly bare thereafter.

Till death us do part

Trouble was also brewing on the domestic front. Montana Bill had reverted to previous patterns of misconduct and was again maintaining a parallel relationship, as an extraordinary metamorphosis got underway. Robert Bailey, the third of his sons to bear that Christian name, was born on February 27, 1917, in Glasgow. The child’s parents were entered as Robert Bailey, a variety artist, and Sarah Phillips Bailey, and, somewhat implausibly, indicated they had been married on June 26, 1915, at Windsor, Canada.

The lady in question was in fact Glasgow-born Sarah McKillop (of which “Phillips” is the anglicised form) (1889–1936), otherwise known as Peteria, Montana Bill’s lovely stage assistant. A further son, Edward, was born on February 2, 1919, in Birmingham.

Then, reversing the normal sequence of events, Robert finally and inexplicably married Alice on September 3, 1919, in Glasgow. His age on this occasion was entered as 48 (actually 49), again making him roughly fifteen years the junior of his “Montana Bill” alter ego. His mother’s name was entered as “____ Robeson, Noeskleta, (deceased),” so that, in effect, we have a hybrid version of the story. He was entered as a “music hall artiste (widower),” but this latter detail is inaccurate since upon her death, the following was recorded: Agnes Johnson, formerly Robeson, widow of Robert Bailey Robeson, died in 1963, aged 85.

Bill also attended daughter Marion’s wedding on the 26th of the same month, but shortly thereafter deserted Alice as abruptly as he had abandoned Agnes.

One of his daughters, Maggie Wade Robeson (1907–1977), suffered from a serious but unspecified disability and was left destitute by her father’s disappearance. Elder sister Marion, by now Mrs. Walker, made an application for Poor Relief on Maggie’s behalf, dated May 21, 1921. This gave their father’s age as 64, just two years short of his manuscript age, and their grandmother was identified as Neoskeleata. This tends to indicate that Montana Bill raised his children to accept his extraordinary legend as fact. In all probability, he had come to believe it himself.

![Detail of Montana Bill's handwritten autobiography, beginning with, "Ladies & gentlemen in endeavouring to give you a short outline of my life for your perusal, I have placed the most prominent incidence[s] before you. Hence should any length of details be found please pardon as lack of space will not permit of more. Yours Faithfully, Montana Bill." Courtesy Tom F. Cunningham at snbba.co.uk.](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=1200,height=993,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=60,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/PW293_MontanaBill-autobiographymanuscript.jpg)

The Essex Years

So, in the time-honoured tradition of the western bad man, Robert Bailey Robeson concocted an alias, reinventing himself as William Montana Bailey. He and Sarah settled in Essex, where they resumed their previous activities. In later years, he pursued a career as a theatrical agent. The couple eventually retired to Southend-on-Sea, where Sarah died in 1936.

William Montana Bailey finally bit the dust on August 19, 1942. His death certificate designated him “formerly a Music Hall Artist” and gave his age as 68, representing an absolute departure from the manuscript version of his life and implying a birth year of ca. 1874.

This embarrassing detail was quickly contradicted by the local paper, which carried a fitting obituary:

DEATH OF A VETERAN

“Montana Bill’s” Career

Mr. William Montana Bailey (“Montana Bill”) who lived in a bungalow in Feeches Road, Eastwood, died at Southend General Hospital on Thursday. His age was indefinite, but it is stated to have been about 80. His son, a member of the R.A.M.C. [Royal Army Medical Corps], visited him one day last week and found him in a state of collapse, and he was immediately removed to hospital, where he died a few days later.

Documents in the house reveal that Mr. Bailey was in the 17th Canadian Rangers and describe him as being a Chief Scout and Indian fighter. After his discharge from the Rangers he joined the 4th U.S. Infantry where he met William Cody (“Buffalo Bill”) the famous U.S. Scout. They left the regiment together and when Cody started a “Wild West” show in 1886, Mr. Bailey joined as a sharp shooter. He later married Peteria, his assistant in the act, who died two years ago.

During the last war, Mr. Bailey was a munition worker at Birmingham. He came to this district 10 years ago, starting a poultry farm at Wickford.

The bit about the poultry farm is probably true. The obituary reunited the two sundered halves of the Robeson/Bailey dynasty when a Scottish relation, who was based at the army barracks at nearby Shoeburyness as a dispatch rider, chanced to read it and presented himself at the front door of the family home.

Persistent rumours of Indians who came to Glasgow with Buffalo Bill and stayed there continue to haunt the city’s East End folklore, and no doubt a large part of the explanation for this engaging urban myth lies in the calculated deceptions of the man who called himself “Montana Bill.”

Today, Montana Bill has living descendants in Glasgow, and Burntisland, Fife, in Scotland, as well as Liverpool, England, and Syracuse, New York. Several are actively engaged in attempting to piece together the truth about the life of their extraordinary forbear.

About the author

For the last two decades and more, Tom Cunningham has pursued an intensive study of Native American history with particular emphasis on connections with Scotland. He is the author of The Diamond’s Ace—Scotland and the Native Americans, and Your Fathers the Ghosts—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Scotland, with much of his research conducted at the Center of the West. In true Cunningham fashion, he encountered Montana Bill as he ventured through the West—and simply had to learn more.

Post 293

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.