Alaska Man, Part 1 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2017

Alaska Man, Part 1

By Mary Robinson

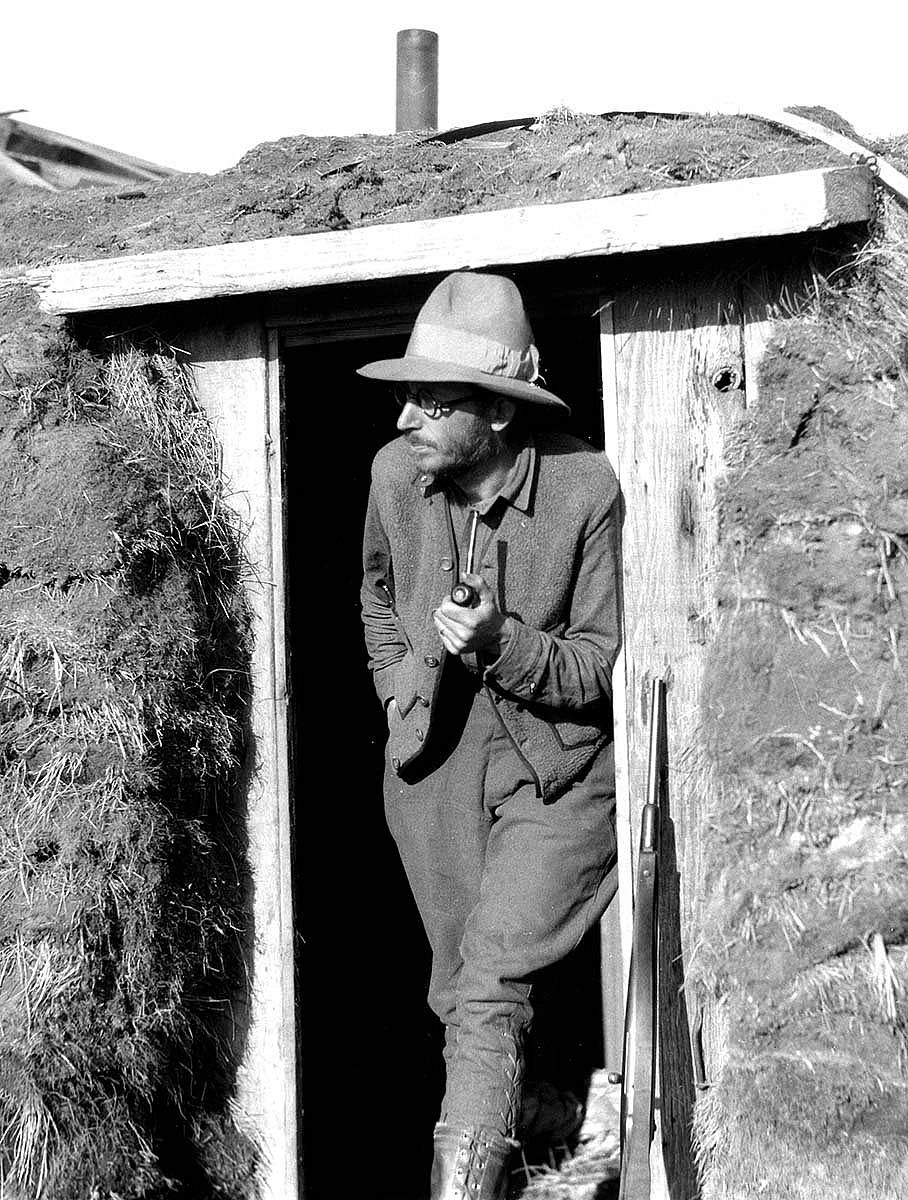

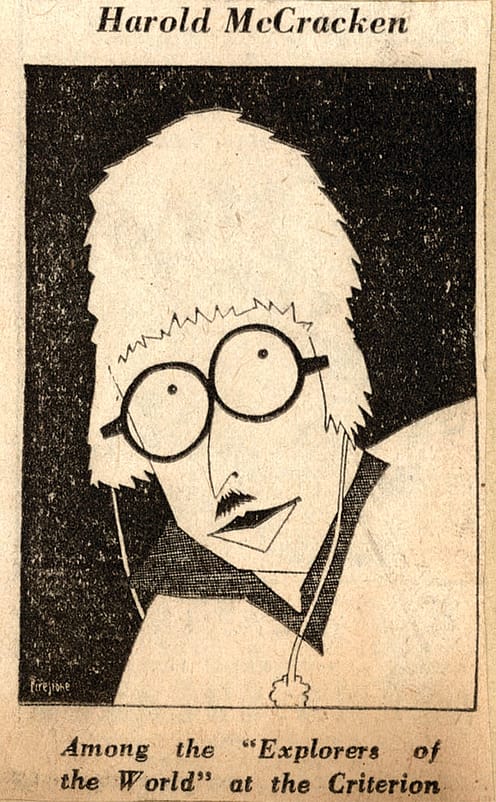

“You’d take him for a schoolmaster, precisely like a schoolmaster, or maybe a scientist. Bald-headed, spectacled, and so skinny you’d think the frost would finish him off the first cold night.”

Such was one journalist’s impression of Harold McCracken (Fig. 1), the young man who would become Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s first director. But frost didn’t “finish him off” in Alaska, and for many years, McCracken carried all that Renaissance Man gusto between Alaska and Manhattan—and numerous points in between, including the American West. As part of its Centennial celebration in 2017, the Center of the West mounted an exhibition to share McCracken’s remarkable story, and how he ultimately found himself in Cody, Wyoming. Mary Robinson, Housel Director of the Center’s McCracken Research Library, wrote this companion article…

Where the North begins

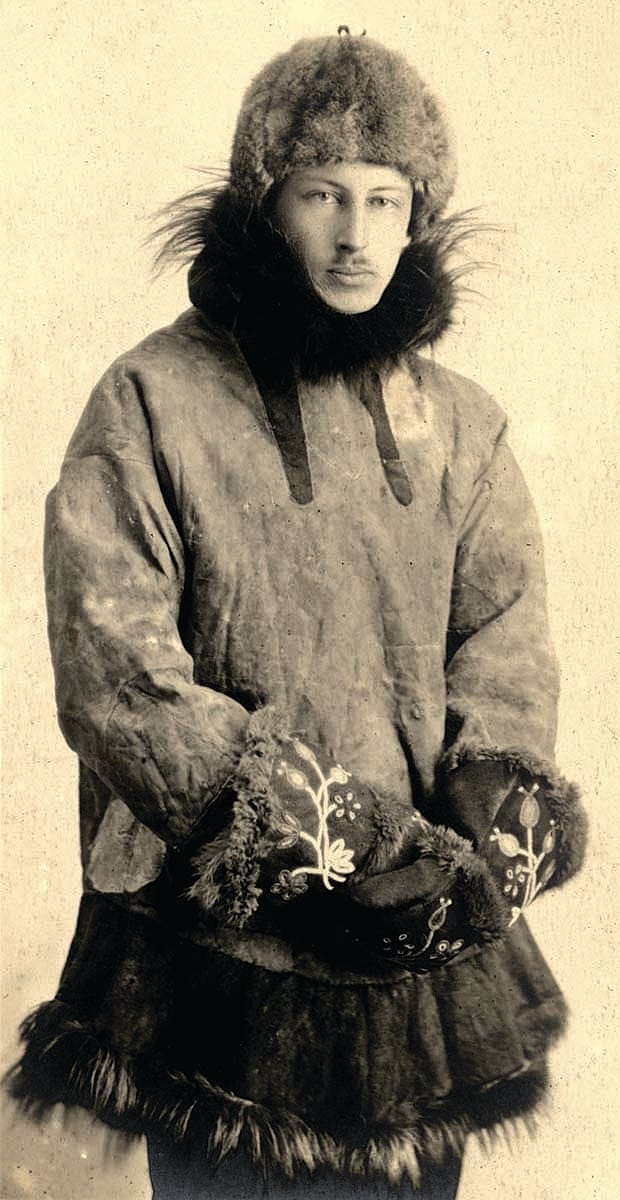

We don’t know who captured this photograph (Fig. 2) of Harold McCracken or exactly where or when it was taken. Dressed for the North Country, McCracken poses for the camera against a blank background that effectively suspends him in time and space. He wears a skin parka, fur hat, and decorated gauntlet mittens. The delicate embroidery on the mittens reflects the sensibility of a native artist. The expressive and rather delicate features of this man suggest something harder to define—an unusual blend, perhaps, of sensitivity and resolve.

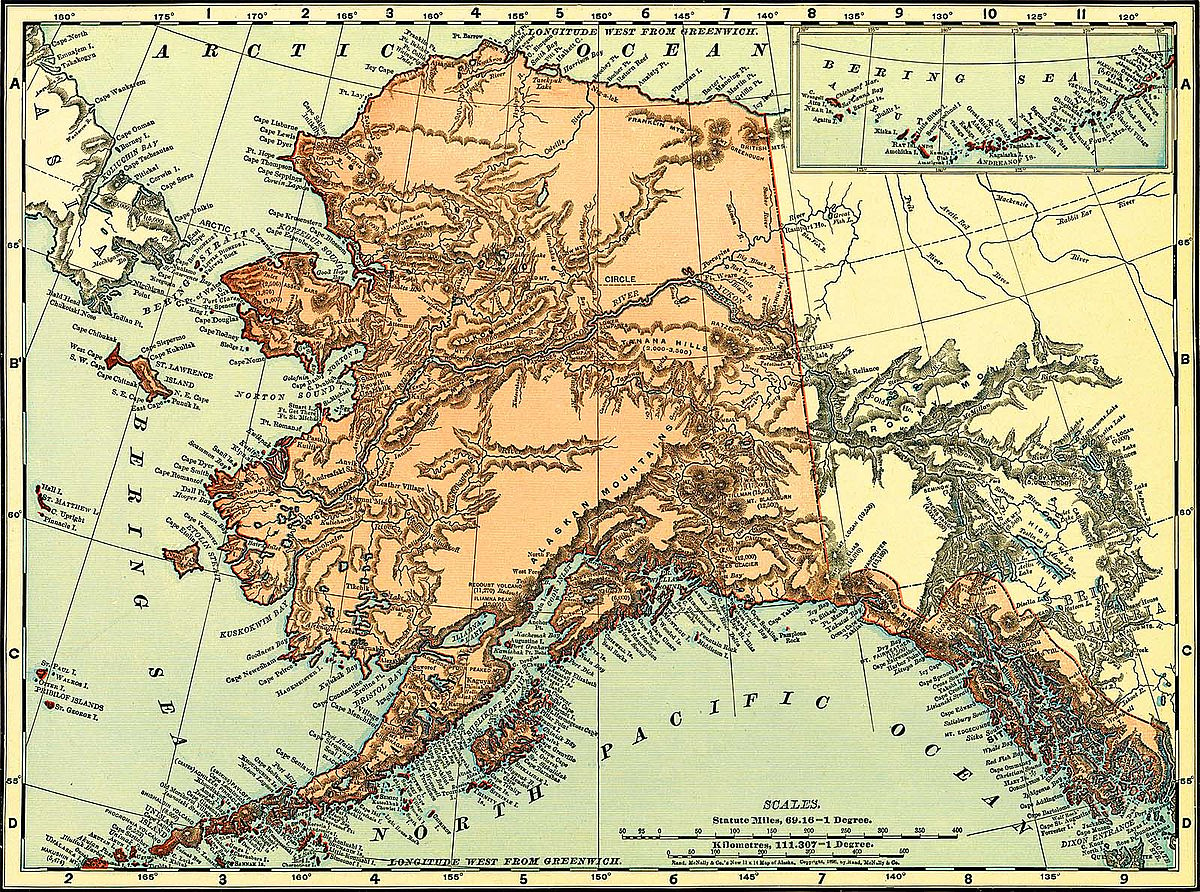

Harold McCracken was born in 1894 in Colorado, the son of a journalist father and an artist mother. As a boy, he fell under the spell of Jack London’s stories. He dreamed of the Klondike, of gold strikes and giant grizzly bears, and the untamed North. While still in his teens, he left school and spent a season in the Canadian Rockies where he met the native Crees and learned how to handle himself in the wilderness. He shot and killed his first bear, and developed a passion for tracking and hunting big game. While his family relocated to the East, eventually settling in Columbus, Ohio, the young McCracken turned his eyes to the North—and to adventure.

McCracken traveled to the Alaska Territory for the first time in 1916 when he was 21 years old. He remained through the winter of 1918 when Fig. 2 was probably taken. Then, like many of his generation, he joined America’s military effort in World War I. He never saw combat, but he got his first taste of New York City while engaged in war-related work at Columbia University. After the war and through 1928, he made several extended trips to Alaska but never lived there permanently.

Men in the hood

The widely published photograph (Fig. 2), would have automatically associated McCracken in the public mind with the most famous of polar explorers, a special breed of men who had achieved unique celebrity. Articles of northern clothing, especially fur-trimmed hoods, were their signature brand. These men were the Gilded Age superheroes of Arctic fame like Robert Peary (Fig. 3) and Roald Amundsen, discoverers of the North Pole and the fabled Northwest Passage, and Captain Bob Bartlett (Fig. 4).

“Men in the hood” knew ice and snow, and the bleak landscapes of the Polar Regions. They had met the native peoples there and just as importantly, their adventures were acted out on a national stage and disseminated through mass media—the newspapers and magazines of the day. They were romantic heroes who offered average Americans an escape from the humdrum and the everyday. Readers followed their trials in the newspapers and lived vicariously through stories of hardship and daring. Many intrepid men in the hood never returned from the North.

With a capital S

By 1916, Americans fully embraced not only the heroism of northern adventurers, but also their contributions in the name of Science. Men in the hood were breaking new ground, observing and recording important information about geography and climate, and flora and fauna. They captured the unique animal species of the North for zoos, or hunted and preserved them for natural history museums. Museum dioramas, which benefited from advances in taxidermy, featured “habitat groups” in the most life-like re-creations. They underscored a new scientific awareness: Humans could not understand wild creatures apart from their environment.

McCracken cast himself in this adventurous mode and explored in the name of Science. The announced goal of his first trip to Alaska in 1916 was to collect specimens of northern big game for a museum at Ohio State University (Fig. 5). He organized the expedition, raised money, and managed to get into the Columbus newspapers. But as Fig. 2 suggests, McCracken went farther than the role of big game hunter: He strikes a self-dramatizing and romantic pose in his parka and beautiful mittens. He dresses like a native of the country and makes clear that, from this time forward, he is a new man. In the most basic ways, McCracken wanted to know the world of Alaska, its landscapes, native peoples, and wild creatures. He hoped to represent it—as in re-create it for others—and to embody it himself.

Alaska Man

He [the bear] was then about 200 yards off—but he looked more like a load of hay than a mere bear.

In this ambition, McCracken was remarkably successful as he became the “Alaska Man” to East Coast radio audiences and magazine readers in the 1920s. Drawing upon real adventures—and in particular on the notoriety of a hunt in 1916 that brought down one of the largest Alaskan grizzlies on record—he lectured and posed for the world in this guise (Fig. 6 & 7). He operated from New York City, which was fast becoming the epicenter of the Roaring Twenties. Soon Broadway furnished one pole of his existence and wild Alaska the other; McCracken possessed the rare, nimble temperament that could navigate both worlds.

McCracken kept himself in the public eye through his association with the northern wilderness, a place of great fascination in the 1920s. He made a remarkable trek that included winter travel by dogsled in 1922 to film Alaska brown bears as they emerged from hibernation in the spring. He talked about Alaska’s native peoples and wildlife on the radio, and he published numerous articles about his hunting exploits in Field and Stream and other outdoor magazines (Fig. 8). By 1924, he was considered a leading authority on the Alaskan grizzly, and in 1925, he was inducted into the Explorer’s Club.

Our Exhibition: Out West where the North begins

This is an American tale—one of adventures, failures, successes, and the forging of a heroic identity based on frontier experiences. The exhibition [which ran from June 3, 2017–February 4, 2018], invited comparison to the story our museum tells of William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody.

Today, Harold McCracken’s Alaska books are mostly out of print, his films largely lost, and his northern accomplishments obscured by the passing decades. The films he made in the 1920s were silent, and his radio talks vanished into the ether. These days, scholars remember McCracken for his contributions to western art, which launched him into a second career as a museum director rather late in life.

But the story the Center exhibition told has as its focus the formative Alaska years. It makes clear how a man of no personal wealth and few connections relied on his native talents to craft a public identity. Harold McCracken became a figure so familiar to East Coast audiences that when he was caricatured in his fur hat, he was often not even named (Fig. 9). Along with his fellow explorers, he was genially mocked for his peculiar costume—but he was also widely admired. So successful was he that on the eve of the stock market crash in October 1929, Harold McCracken had achieved what we would call “name recognition” on a national scale. How did this happen?

Deliverables

Simply put, Roaring Twenties audiences sought novelty—and Harold McCracken delivered. This was the era, after all, of wing-walkers, flappers, and speakeasies—of risky business in an Art Deco city overflowing with money and champagne. This was the decade when the tomb of Tutankhamen, with all its golden riches, was revealed to the world. This was a time of fascination with the strange and exotic, when a young black performer named Josephine Baker from St. Louis danced for all of Paris in La Revue Negre. The public appetite for novelty drove the wild aerial stunts and goofy fads that we associate with the period. That appetite was only whetted by the proliferation of new media: radio (Fig. 10), motion pictures, newsreels, and popular magazines.

In this maelstrom of cultural change, McCracken found his niche. He mastered his craft—that of action filmmaking—to reveal the exotic to his audiences, in this case Alaska wildlife and peoples. If the subject matter seems in odd contrast with sleek, daring fashions; nightclubs; and jazz music, McCracken’s audiences appeared not to notice. In his book The War, the West and the Wilderness, Kevin Brownlow discusses this trend among silent movie-makers to forsake the studio for dangerous and exotic places like Africa and the South Sea Islands. They fanned out across the globe during this period, and no corner of the world was safe from these bold, enterprising people and their cameras.

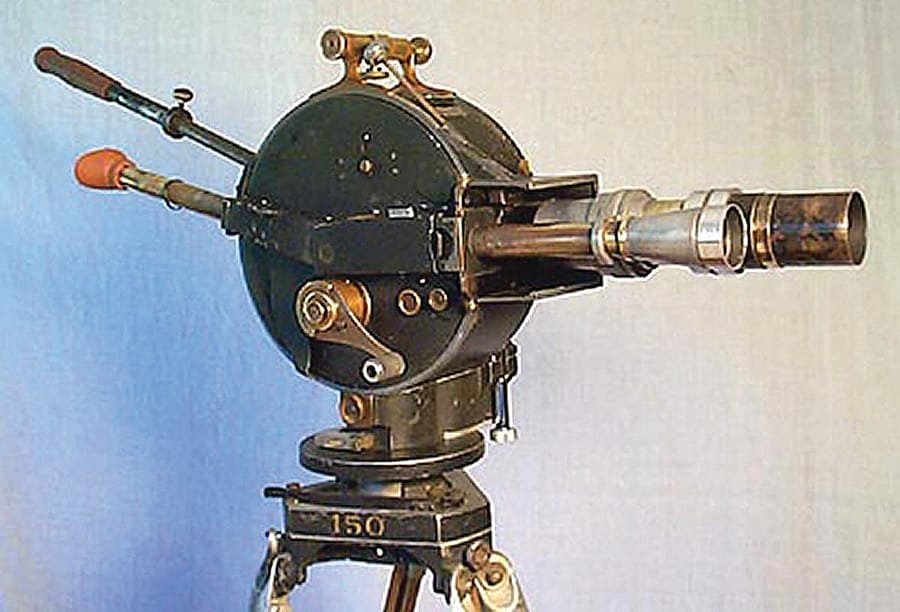

But McCracken was no studio man. Always a maverick, he was essentially a free spirit who had earned his credentials in the Alaskan bush. However, in 1922, when a wealthy patron from Columbus hired him to be a hunting guide and bought him a state-of-the-art film camera, the young adventurer quickly conceived his own plans for filming in Alaska. In time, he became a self-taught, wildlife documentarian. As such, he joins the elite company of Lowell Thomas, Martin and Osa Johnson, and others who lugged their hand-cranked cameras to the unexplored regions of the world.

The “Go-Pro” of the 1920s

McCracken filmed the gigantic bears and moose of Alaska using an Akeley camera, the brilliant invention of taxidermist and filmmaker Carl Akeley. The “pancake,” as it was called (Fig. 11), was specially designed to capture motion, and McCracken exploited his camera’s full potential in the field. He toted the heavy Akeley and tripod through winter snow and across wind-swept, bug-infested tundra to snatch his footage. With one companion, the soon-to-be famous hunting guide Andy Simons, McCracken filmed Kenai moose and even more remarkably, the famous Alaska brown bears in their native habitat.

To accomplish this, the two men ventured into places that today are still wild and inhospitable. Over time, they learned to mimic the animals’ habit of sleeping in the middle of the long Alaska day. Filming only began at dusk when the bears left their daybeds and gathered at the streams to gorge on salmon. They greeted each other, jostled for position, and settled in for a night of good eating, a scene inexpressibly marvelous for two young adventurers.

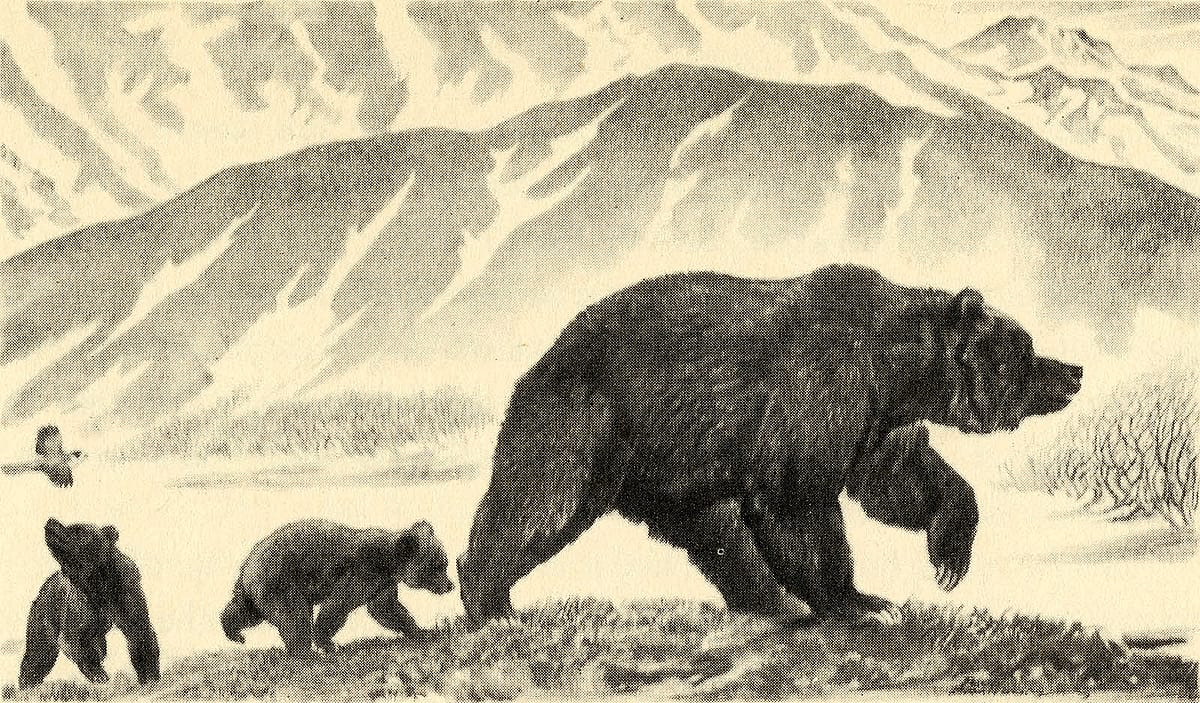

For weeks McCracken and Simons tried to find good angles for shooting film, but the flat coastal lagoon country with its high sea grasses often obscured their hulking subjects, who, after all, were not interested in making good movies. After many trials and failures, the pair discovered a special place they called “Nursery Valley,” which was the haunt of a sow grizzly and her two cubs (Fig. 12). Here the terrain offered McCracken an advantage: He could film from the relative safety of a high bank that overlooked both the hillside opposite and the salmon-choked stream. Day after day, the bear family returned to this movie set, earning names like “Rough-neck” and “Apron-strings,” and becoming film stars in the process.

Rough living

Given the primitive remoteness of Alaska in 1922, it is almost impossible to exaggerate McCracken’s achievement in making these films. Facing down bad weather, tough terrain, and unpredictable—not to say dangerous—subjects, McCracken endured eight months of rough living on the Bering Coast of the Alaska Peninsula to attain his ends (Fig. 13). He and Simons enjoyed only the crude shelter of partially underground native trapping dwellings known as barabaras (Fig. 14) at night and a simple folding canvas canoe for travel by day. Their clothing was soaked in the rains that swept over the Peninsula, and their feet stayed wet for weeks.

The story, recounted in McCracken’s Alaska Bear Trails, describes more than a few hair-raising moments when the cameraman abandoned his expensive equipment, and the two explorers took to their heels. High-powered rifles were part of their outfit, but they never found it necessary to shoot one of these bears except with the Akeley.

The result was something never before seen by most Americans: Alaskan grizzlies going about their daily lives; bear families feasting on the bounty of salmon; and cubs learning the hard lessons of survival. McCracken offered perhaps the first glimpse of a running grizzly bear, and his panning camera caught the power and agility of these animals as they charged through the alders. The men began to recognize marked personality traits in their subjects and named them accordingly. That bears were unique individuals was a fresh notion that Science and the public had not fully appreciated at the time.

The sheer concentration of these bears in coastal Alaska was a revelation. McCracken and Simons observed 190 individuals in a single season, a fact noted by Olaus Murie in his 1959 study of the species. They spotted as many as twenty-eight bears in one day, and twelve on the same salmon stream in full view of one another—a memorable occasion to be sure. McCracken wasn’t able to successfully capture all these scenes on film, but in Alaska Bear Trails, he detailed rarely seen social interactions among Alaskan grizzlies. He recalled that wondrous summer as “the greatest of all my wilderness experiences.”

McCracken deserves much credit for helping to popularize wildlife films when the genre was in its infancy. Today “nature programs” are ubiquitous, and the best filmmakers pursue their craft with a technical sophistication beyond anything imaginable in the 1920s. But one secret of success still applies today, and McCracken, with his excellent instincts, grasped it from the start: Nature films must entertain as well as inform. McCracken’s Alaska films appear to have struck that balance, and when he showed them at New York City’s Capitol Theatre in 1923, he scored a hit with the public. Soon such films became his stock-in-trade.

In lecture halls and on the radio, McCracken also enlightened audiences about Alaska’s native peoples, particularly the Aleuts with whom he lived and traveled, and the Inupiat on Little Diomede Island. He observed their customs, listened to their stories, and photographed and filmed them in ceremonies and dances. Fragments of these films have survived, but McCracken’s lecture notes have not. His interviews with reporters, however, reveal his penchant for yarn-spinning and offering the colorful detail that engages an audience.

A modest chap

In an interview in the Boston Evening Globe (1932), for example, the journalist introduces McCracken as “a very modest chap, whose easy voice and manner give no hint of his career into frozen places.” To this McCracken replies, “Freezing to death is very easy. I know for I’ve been on the verge of it.” In discussing the short growing season in the North, he observes that, “The largest strawberry patches in the world are in Alaska. The berry is small but sweetly toothsome.” McCracken had a way of surprising people with facts about Alaska that contradicted their assumptions. “McCracken jolts us on many matters,” the reporter admits, “wherein our information was apparently all wrong.” The savvy explorer knew how to play on his public’s lack of knowledge to dramatic effect.

Reporters seemed much amused by the contrast between McCracken’s appearance and his outsized accomplishments. By his own description a tall, rangy fellow, McCracken was far from a typical outdoorsman, and he was visibly balding in his twenties. “You’d take him for a schoolmaster,” one baffled writer observed, “precisely like a schoolmaster, or maybe a scientist. Bald-headed, spectacled, and so skinny you’d think the frost would finish him off the first cold night.”

But while he could entertain reporters with light commentary, McCracken could also fascinate more learned and experienced people. His growing reputation as an authority on wildlife drew the attention of the National Geographic Society (Fig. 16), the Campfire Club of America, and other outdoor organizations. His films of grizzly bears on the salmon streams of Alaska were entirely new and absolutely thrilling to sportsmen. This success attests to McCracken’s talents, his versatility, and his ability to adjust his subject matter to an audience. Family scrapbooks reveal a lively schedule of talks to groups up and down the East Coast. Unfortunately, the lecture circuit did not provide a living in the 1920s, and to earn his daily bread, McCracken sought other sources of income. Soon he discovered other novel—not to say sensational—uses for his Akeley camera.

In the next installment of Points West Online, the Alaska story continues as Alaska Man shares more about McCracken’s exploits there, his writings, and his legacy at the Center of the West.

About the author

Mary Robinson has been an active professional in the Wyoming library community since 1993. She holds an MLS degree from Emporia State University in Kansas and a Special Collections Certification from the Graduate School of Library and Information Science at the University of Illinois. She became the Housel Director of the Center’s McCracken Research Library on April 1, 2010.

Post 295

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.