Alaska Man, Part 2 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2017

Alaska Man, Part 2

By Mary Robinson

In part one of Alaska Man, we learned how Harold McCracken publicizes his northern adventures to establish himself as a public figure. Each of his first two expeditions to Alaska was a “roll of the dice for McCracken,” who risked himself in wild country to achieve important goals, and win an audience for his stories and lectures.

In the third and most ambitious expedition, he leads a museum party to Alaska and the Arctic, and gains an even larger measure of fame. But there was that little problem of income…

High-flying newsreel cameraman

Then as now, Alaska was a remote and expensive destination. Harold McCracken the explorer was a high-profile but very likely low-budget operator during these early years. He could afford his trips to the North when sponsored by a museum or hired as a hunting guide, but by 1924, he wanted to marry his sweetheart from Columbus, Ohio. We might guess that her family found his profession to be colorful but hardly remunerative. At this point, McCracken earned income from his writing for Field and Stream and would eventually be hired as an editor of the popular magazine. He also worked for the publishing magnate George Palmer Putnam. Apparently, it was not enough to keep him in funds.

To make a living in the increasingly fast-paced world of New York City, McCracken became a specialist in filming aerial stunts for film company Pathé News. Using his Akeley camera, he captured the action in the skies—newly populated with “aero planes.” His films were incorporated into newsreels, a popular medium for news or entertainment in public movie houses.

But the entertainment value of the footage rose with the riskiness of the stunts, a risk shared by the pilots, cameramen, and athletes performing them. In fact, these assignments were so dangerous that McCracken was hired strictly by the job. He would climb aboard a bi-plane and sometimes crawl out on the wing to film an acrobat performing a perilous maneuver out of another plane flying close by.

Research has uncovered some of these films. Still photos from the shoots have been matched up with actual footage, so there is no doubt that McCracken was behind the camera. He filmed from airships—the famous blimps of the era. He also filmed races, prize fights, and other newsworthy, dramatic events. The money was good, but in this work, he was largely anonymous. Yet, it was all in the pursuit of opportunities to get to Alaska.

![McCracken with prizefighter and boxing Hall of Famer Harry Wills, October 12, 1926. Caption reads "before Wills-[James] Sharkey fight, Phil." MS 305 Harold McCracken Photograph Collection, McCracken Research Library. MS305.01.004](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=1200,height=938,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=50,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/PW296_McCrackenprizefighter_MS305.01.004.jpg)

Big plans: the Stoll-McCracken Siberian-Arctic Expedition of 1928

To sustain his notoriety and burnish his explorer’s reputation, McCracken had to keep his name before the public. Therefore, he announced his goals to newspaper reporters before embarking on adventures. This is the definitive “going out on a limb,” a different kind of risk obviously, and the bigger the quest, the better it played in the press. By sharing his plans with reporters, McCracken raised expectations and the stakes. In most cases, he returned with his reputation intact and with an authority based in experience. This was the authority he had earned when other types of authority were not available to him.

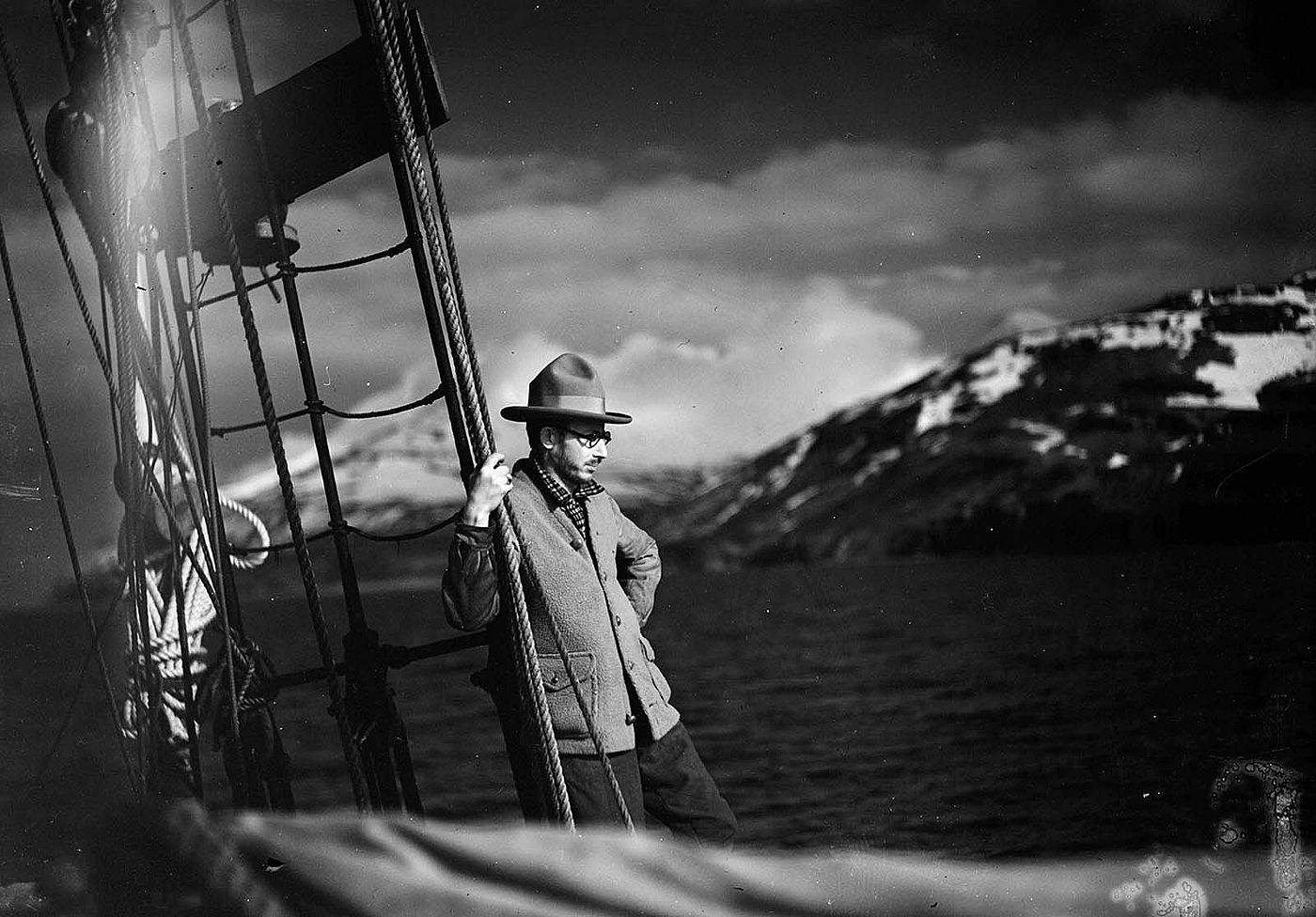

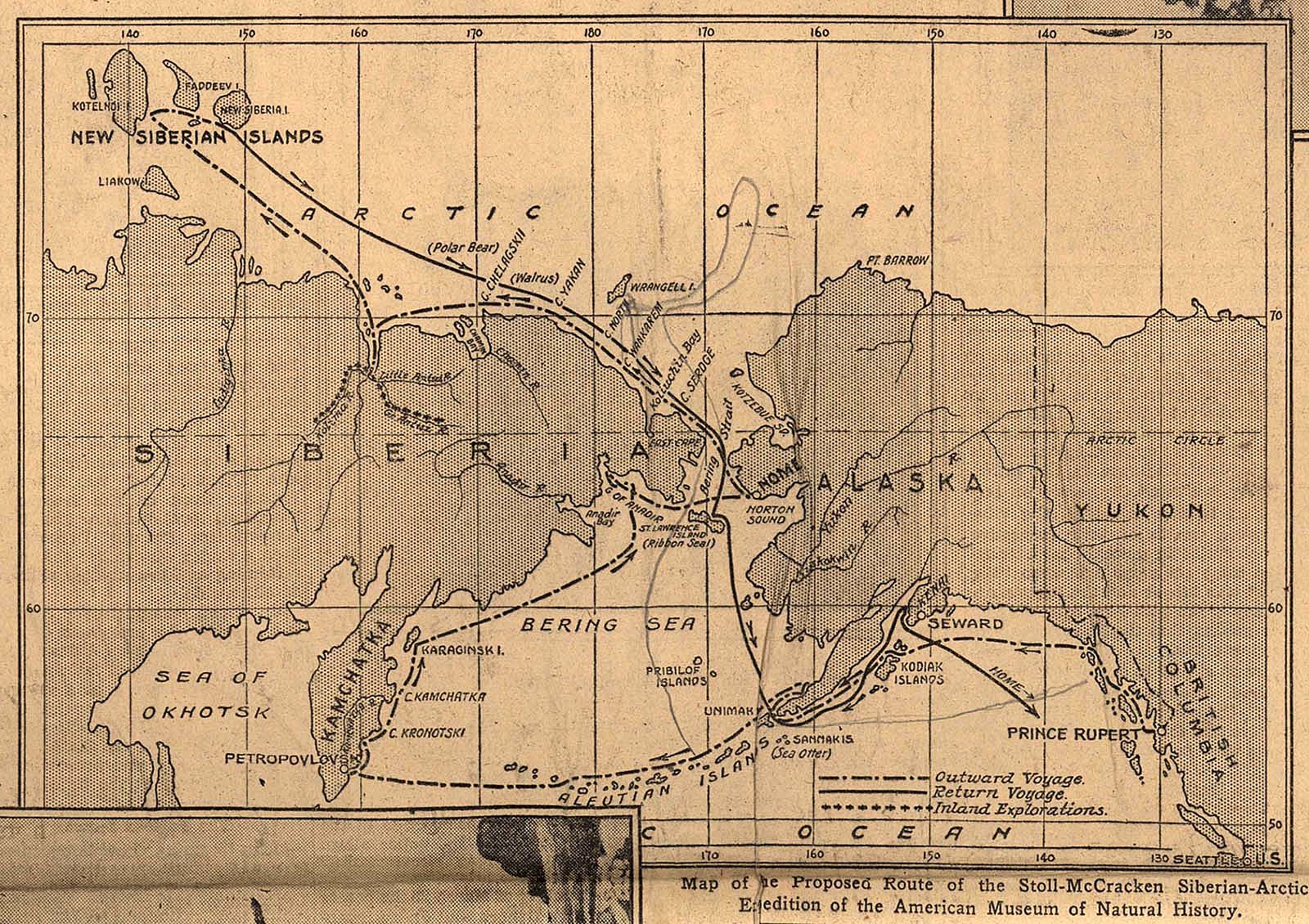

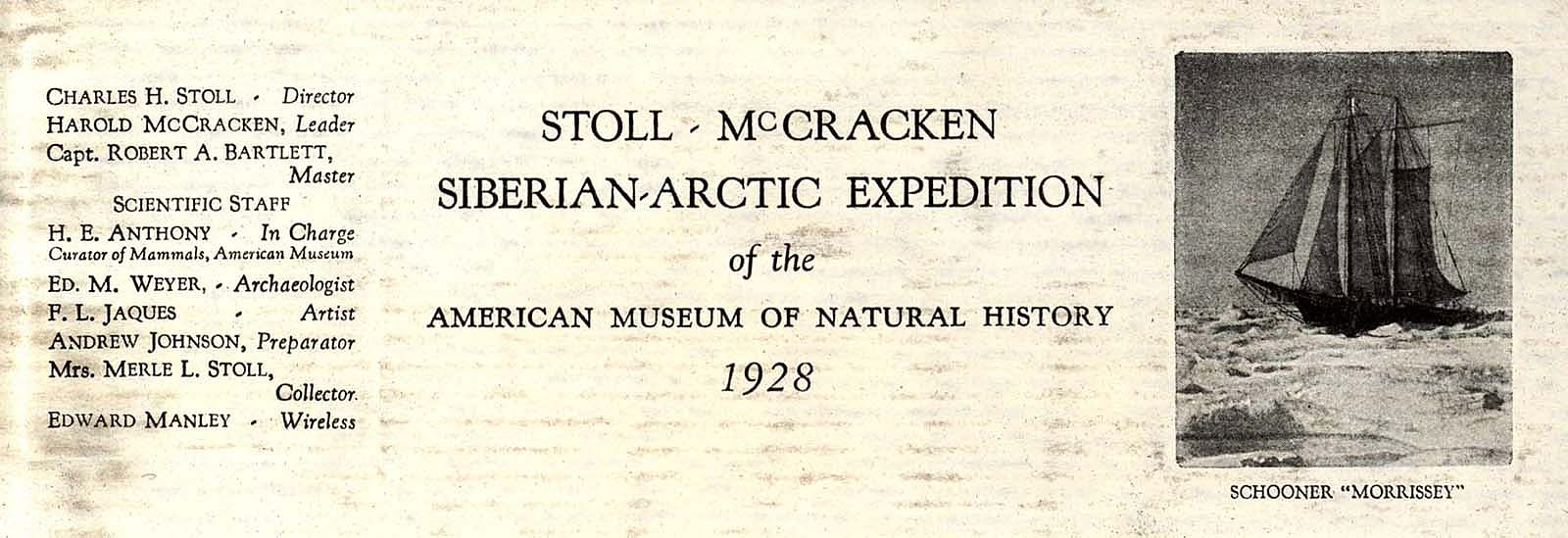

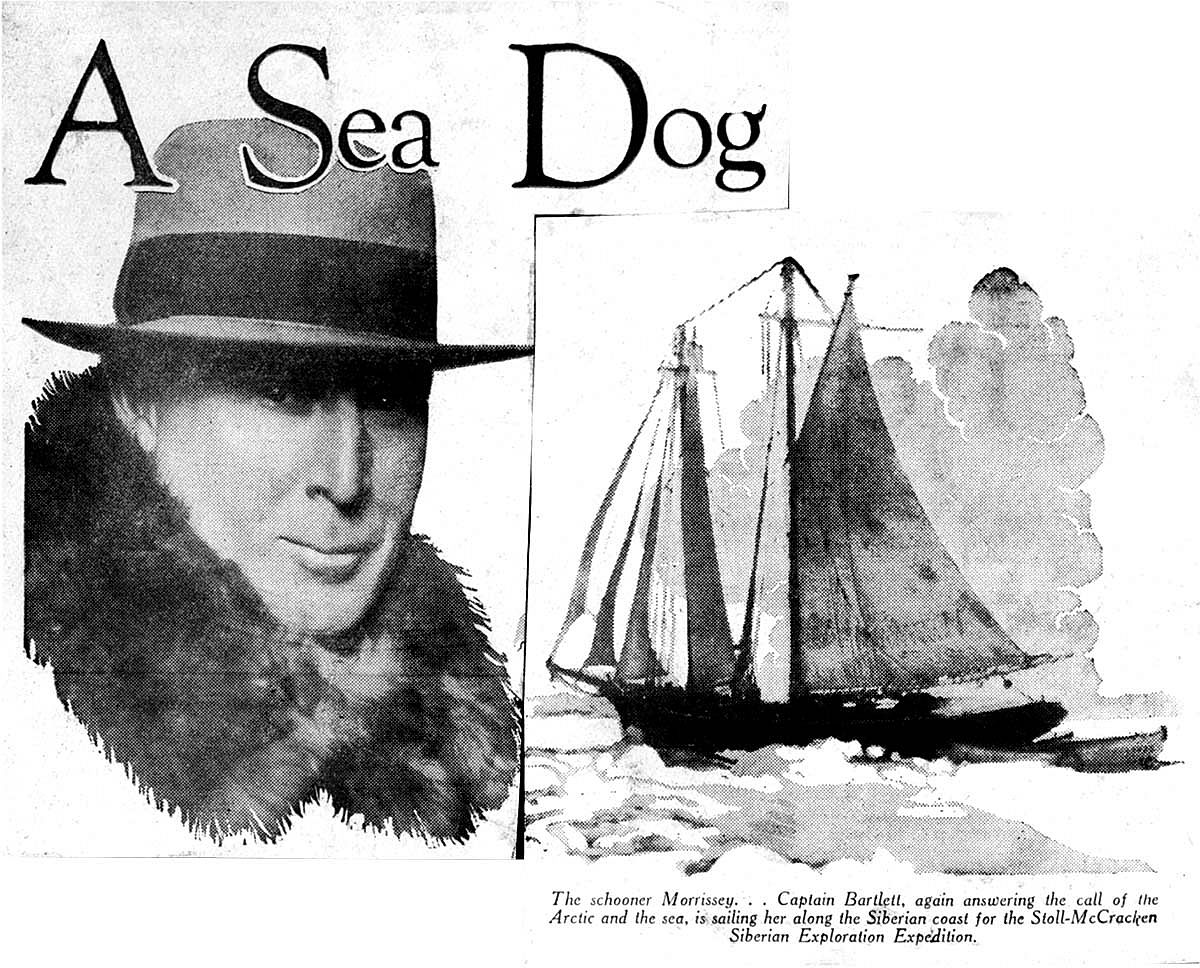

Thus in 1928, when he proposed and organized a collecting expedition for the American Museum of Natural History, McCracken’s objectives were widely covered in the press. The goal was to obtain northern species for the newly planned Hall of Ocean Life and to conduct archaeological excavations. To accomplish this, he and his companions would sail on the famous schooner Morrissey to the Alaska Peninsula, and then on north through the Bering Strait to the remote Chukchi Sea. They would collect bears for a diorama group and hunt Pacific walrus on the edge of the pack ice—a dangerous proposition at the best of times. Their success would depend on luck, fortitude, and the knowledge of Alaska’s coastal waters that only McCracken and the ship’s captain, the famous navigator Robert Bartlett, could provide.

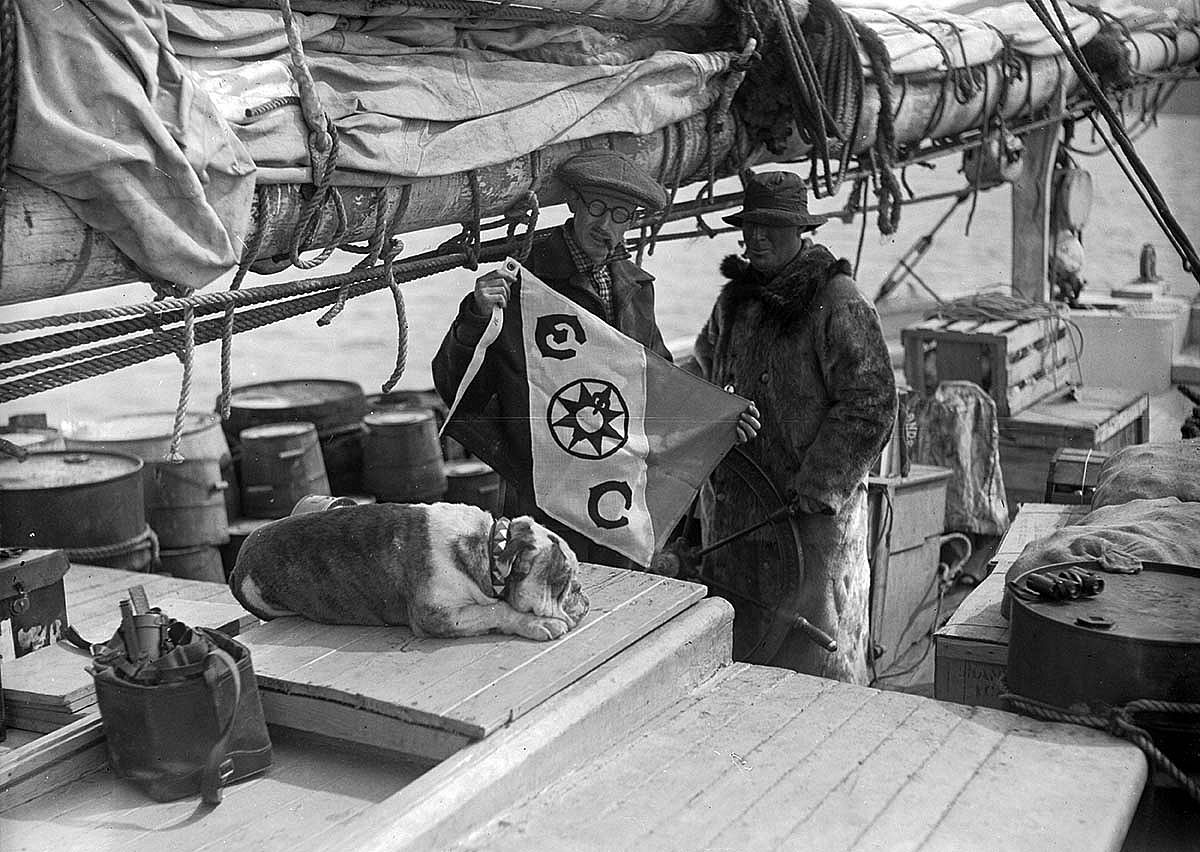

The party included men of established reputation like Bartlett, but also museum scientists destined for distinguished careers, and the diorama artist Francis Lee Jaques. McCracken raised the stakes by announcing to the press that the voyage would be conducted under the flag of the prestigious Explorers Club, headquartered in New York City. The expedition would search for Aleutian mummies, whose existence was believed by some to be important evidence of the “First Americans” to migrate from Asia to the New World. William Healy Dall of the Smithsonian had reported on the practice of mummification in Alaska, but the claim had not been verified. McCracken seized on this goal to capture attention. And ever the showman, he also brought along a bulldog named “Toughy” as ship’s mascot to add color and interest to the story.

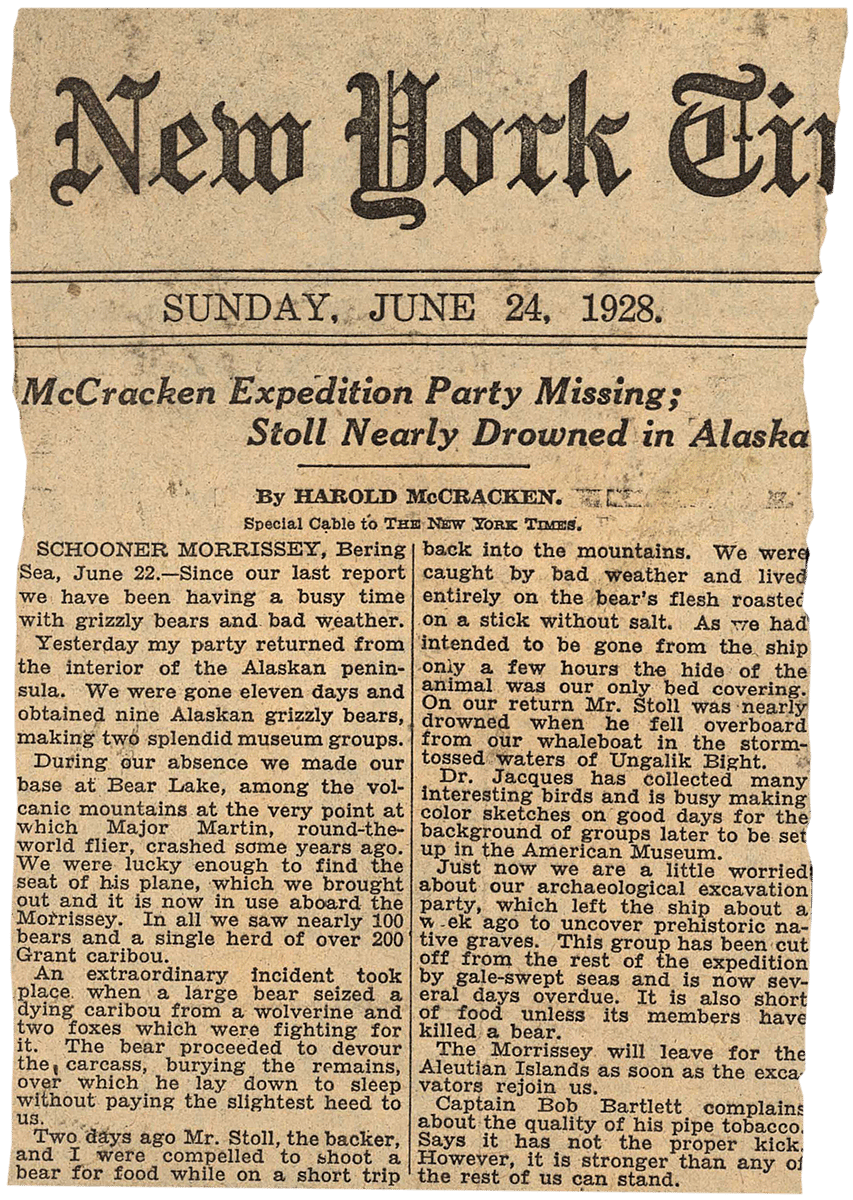

Northern blogger

During the voyage, McCracken was under contract to the New York Times to send wireless dispatches that recounted their adventures in real time. His reports were relayed by amateur wireless operators to the Times. “On Board the Schooner Morrissey” was the eye-catching phrase that signaled another dispatch from the expedition. This was reality journalism—a sort of 1920s blog—and to all appearances, readers followed the expedition with great enthusiasm. Bear hunts on the tundra, strange clues from old Aleuts that led to discoveries, narrow escapes for the Morrissey in the ice floes—all made for sensational copy.

In seeking publicity, McCracken fulfilled his explorer’s duty, which was to push the boundaries of the known and do it in a very public way. Upon his return to New York, he published extensive articles in the New York Times that news agencies picked up and printed in papers across America. When he wrote his books in the 1930s about what it all meant, he offered as much knowledge as most people possessed at the time.

Perils of the North

We must confess that Harold McCracken occasionally exaggerated the risks of the journey. For the sake of a good story, the hero was not above inventing drama. An incident in July, when the party left the Aleutians and headed north toward the Bering Straits, illustrates the point.

The Morrissey had been specially equipped with an engine for extra power and maneuverability, but while they were cruising in the open Bering Sea, the propeller shaft suddenly broke apart. The schooner limped into Grantley Harbor on the Seward Peninsula, and it looked as if the expedition might end there.

The reason for the break was not entirely clear, but McCracken’s wireless dispatch to the Times described high seas and hinted at a collision with pack ice—all this while the ship was crossing relatively calm, ice-free water. McCracken was fully aware that an earlier accident had likely damaged the shaft, but he led his readers to believe otherwise. Jaques later observed, rather dryly, that McCracken’s accounts of the expedition “made for very interesting reading.”

In fact, the expedition continued north after Bartlett located a new shaft at Nome, had it transported to the beached ship, and fitted it on site—a remarkable accomplishment for the crew. They went on to survive near-disasters when the Morrissey might have gone to the bottom in the pack ice of the Chukchi Sea. The hero of these episodes was the skilled and resourceful Bartlett, who wrote his own account of the voyage in Sails Over Ice (Scribner’s, 1934).

At this stage, McCracken was a passenger like everyone else, but he had proved indispensable as a guide when the party spent the month of June on the Alaska Peninsula hunting grizzly bears and conducting an archaeological dig near Port Moller. He and his cohorts also fulfilled their duty as explorers by discovering Aleutian mummies. This was spectacular success by any measure but at times, McCracken the blogger was decidedly a spin master.

Poet of the North

Northern adventures—and his ability to publicize them—brought fame to Harold McCracken in the 1920s. But fads eventually die out, and the financial crash that brought on the Great Depression made big expeditions unaffordable and the explorer’s profession a bit old-fashioned. While he coasted on his celebrity well into the 1930s, the culture was changing again, and McCracken, now the head of a young family, was out of a job unless he could parlay his experiences into other forms of income. To use a contemporary phrase, he had to pivot. As usual, McCracken made a success of his new enterprise, becoming a sort of poet of the North.

In 1930, he published his first book about Alaska, Iglaome, a novel about a Native boy. Several books recounting McCracken’s adventures followed: God’s Frozen Children, Alaska Bear Trails, and a second novel, Beyond the Frozen Frontier. He also toured with a group of adventurers, showing films, sporting a tuxedo, and showing off his famous bear hide on Broadway. Explorers of the World, as the program was called, gave him top billing among such luminaries as James L. Clark and Harold Noice. Now his bald head and cigar, rather than a fur hat and pipe, became his signature brand.

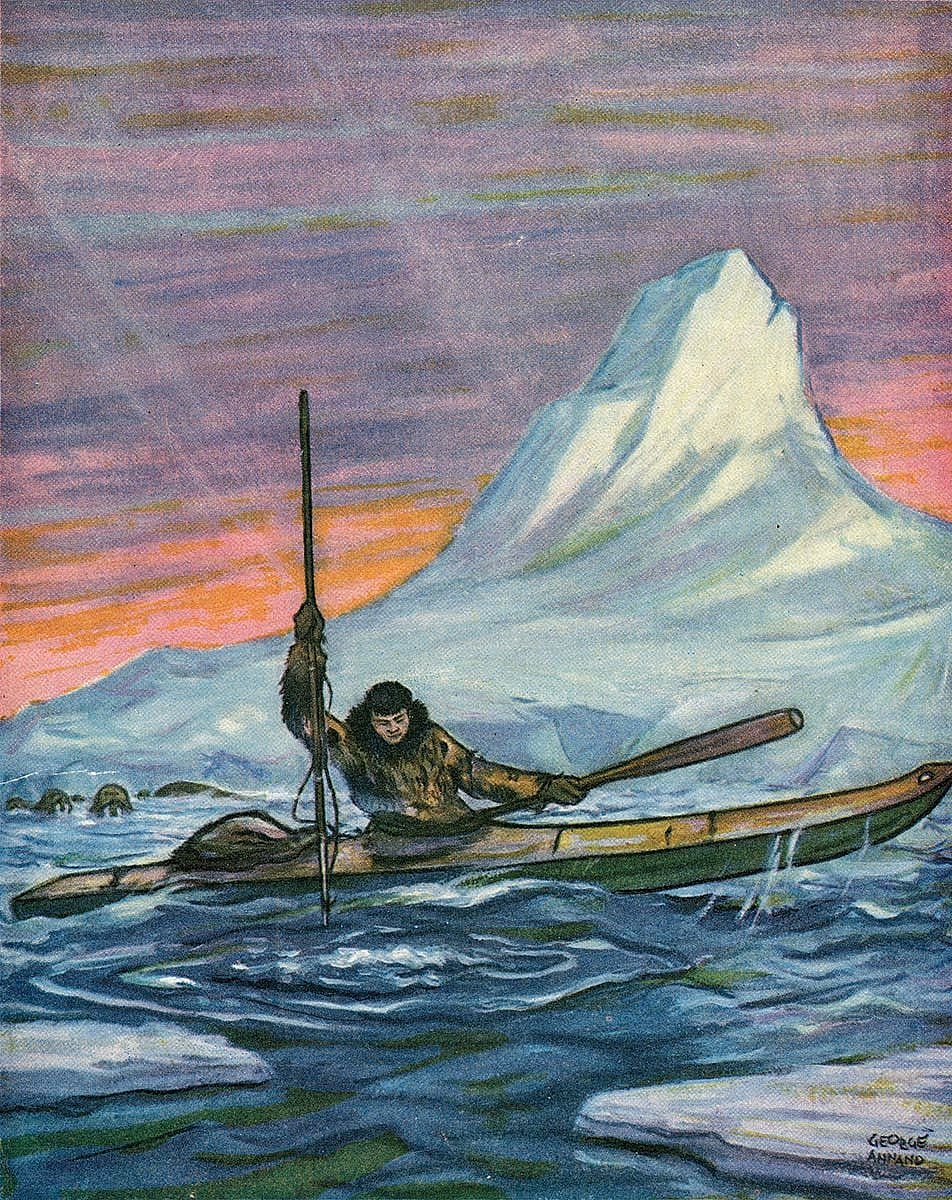

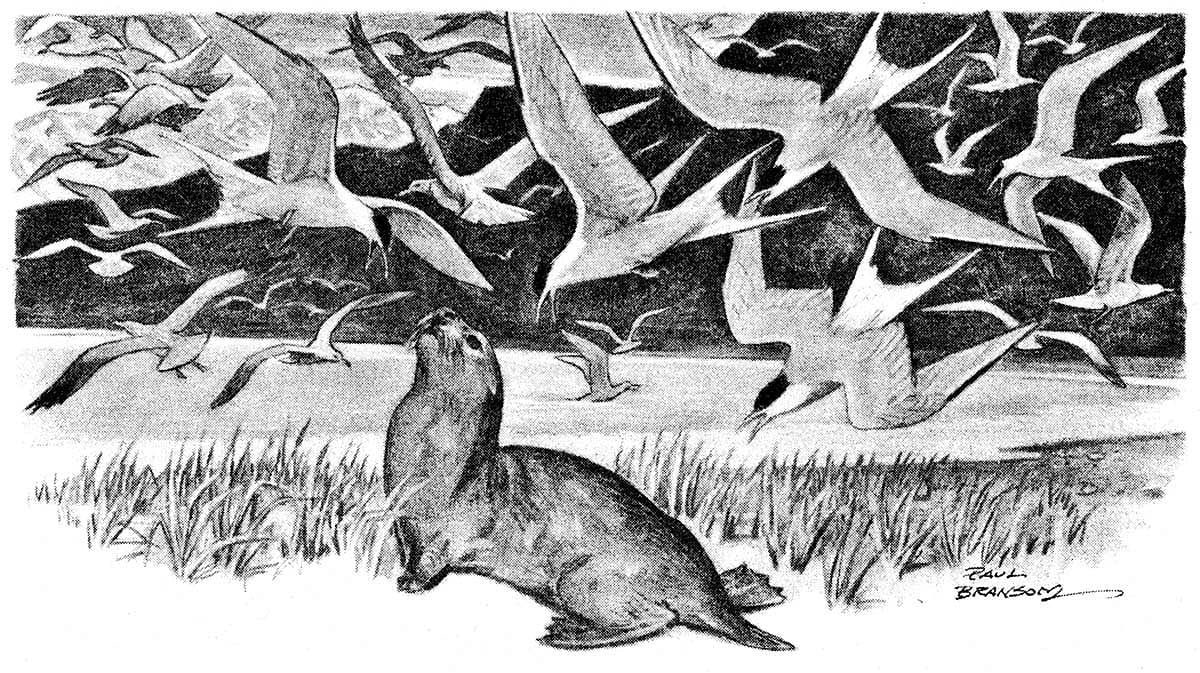

But financial success eluded him until the 1940s when Lippincott published his series of illustrated books about Alaska wildlife for young people. The titles—The Last of the Sea Otters (1942), The Biggest Bear on Earth (1943), and The Son of the Walrus King (1944)—are suggestive of the extremes Alaska inspired as the home of some of the biggest, the strangest, and the most fascinating species. These superlatives are McCracken’s muses, but in his later writings, he did not distort or exaggerate.

Rather, his stories placed northern animals in real landscapes of natural abundance and great beauty. He showed these creatures as they are—subject to threats like weather and accidents and dangerous predators, prone to suffering and loss, and above all, striving to survive. McCracken described species like the vulnerable sea otter, balanced on the brink of extinction and menaced by human hunters. At his most effective, Harold McCracken showed the American public how the cold-adapted species of Alaska were perfectly at home in climatic extremes, but poignantly hemmed in by man-made threats. In this, he was ahead of his time and prefigured nature writing of the later twentieth century. In the 1940s, young readers by the thousands made McCracken a trusted guide to the wonders of the North. Many of the best wildlife illustrators of the day, Lynn Bogue Hunt to name but one, enhanced these delightful books.

Natural educator

What distinguishes Harold McCracken throughout his career, and wins our admiration today, is his persistent effort not only to engage people, but to teach them. McCracken, for all his maverick ways, was a natural educator. We find this in his earliest work as a type of hunter-naturalist who shared his curiosity and wonder about the northern world with his audiences. In an important personal development, McCracken-the-hunter became a reluctant killer, and spent more and more time advocating for better understanding of these animals—especially grizzly bears, which he called “wonderful” and deserving of respect.

The sense of wide-eyed wonder about the place, the people, and the creatures that persist in that northern climate—this is the undercurrent of McCracken’s best work. His prose is vivid, exact, and evocative of the North Country. His experiences traveling the bleak coasts of the Bering Sea or riding the bowsprit of the schooner Morrissey became high drama in his stories for young people. The avuncular tone and assured style of his writing from this period emanate from a new authority, that of a writer who has found his subject at last. Iglaome was followed by more than thirty books, the most successful being his “animal biographies,” as he called them, which enthralled a generation of American readers.

Museum director

The time frame of McCracken’s career fits nicely into the development, institutionally, of our Buffalo Bill Center of the West. He journeyed north to adventure in 1916, the year before William F. Cody’s death and the establishment of the Buffalo Bill Memorial Association. That connection in time is wonderfully serendipitous, given his later role in developing what would become the Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

Today, in addition to museums about western art, Plains Indians, Buffalo Bill, and firearms, we have a natural history museum where grizzly bear behavior is featured prominently and interpreted. This focus would have pleased Harold McCracken. He would have recognized that his contributions to American museums had come full circle. Thus, the sphinxlike McCracken—explorer, naturalist, wildlife filmmaker, writer, and western art historian—connects past to present for us. His work after 1959, when he was hired as the first director of the Whitney Gallery of Western Art, is revealed, you might say, as the DNA of our institution.

When you visit, look around, and you will see Harold: in the macroenvironment, in the Remington Studio and Plains Indian artifacts, and in the structure of our museum complex. Dig a bit, and you will discover him in the microenvironment, in paper records and letters, and meeting minutes. He most likely appears in registration records and in the Whitney western art collections.

After the years of adventure, Harold McCracken journeyed north in his imagination. Before he was done, he had written novels, stories, articles and histories—even a “musical poem” about Alaska called Out West Where the North Begins. During an especially productive period in the 1940s, he began to publish on another, quite different subject, the art of Frederic Remington…and the Center of the West is all the better for it.

About the author

Mary Robinson has been an active professional in the Wyoming library community since 1993. She holds an MLS from Emporia State University in Kansas and a Special Collections Certification from the Graduate School of Library and Information Science at the University of Illinois. She became the Housel Director of the Center’s McCracken Research Library on April 1, 2010.

Post 296

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.