Margaret Murie: Sunlight Aura and Spine of Steel – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2003

Margaret Murie: Sunlight Aura and Spine of Steel

By Valarie Hamm

Former Intern, Draper Natural History Museum

Nestled in a log cabin in Grand Teton National Park, one of the environmental movement’s most influential spokespersons—Margaret Murie—rests quietly in her wheelchair. At nearly 101 years of age* the woman who helped set the course of American conservation more than 70 years ago has aged and grown quiet. Her clear voice is no longer heard at congressional hearings; her pen no longer translates the beauty and purpose of nature onto paper.

Yet even in her declining years, Mardy’s mere presence—and the legacy she and her husband, Olaus, created—still has force and power. “When people learn about Mardy, it inspires them to do what they can for wild places,” said Nancy Shea, director of the Murie Center, a non-profit organization dedicated to the Murie family legacy of defending wilderness. “She’s got the ability to move people toward action.”

The “Fairy Godmother” of the conservation movement, Mardy is best known for her work to secure two major wilderness areas, Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming and Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. She also worked with other conservation leaders to bring about the passage of the 1964 Wilderness Act, legislation that enabled Congress to set aside select areas—in national forests, wildlife refuges, parks and other federal lands—to be kept permanently unchanged by humans.

“She was a great influence,” said Donald Murie, one of Mardy and Olaus’ three children. “She has this sunlight aura that warms up the space around her. At the same time, she has a spine of steel and can nail you with her eyes.”

Mardie’s Migrations

Born in Seattle in 1902, Mardy and her family moved north to the booming gold town of Fairbanks, Alaska. This proved to be a turning point in Mardy’s life. While her mother struggled to find her place in the middle of a vast wilderness, Mardy thrived on what she described as the “wild, free, clean, fragrant, untrampled” nature of the land. “I think my mother felt the unspeakable isolation more than she would ever say,” Mardy wrote. “I realize now that I felt this in her, even while not feeling it myself at all. To an eager, curious child, everything was interesting.”[1]

When Mardy was old enough to attend college, she headed south to “’The States’…that other world which seemed to have very little to do with us.” Her family encouraged her to become a secretary, but after spending two years at Reed College in Oregon and one year at Simmons College in Boston, Mardy returned to her homestate. She continued her business studies at the University of Alaska, and in 1924, became the first woman to receive a degree from the university. “There was a beautiful, full commencement ceremony, for which notables of the Territory came and the whole town, it seemed turned out,” wrote Mardy. One of those not present, however, was Olaus Murie, a pioneering Arctic field researcher—and Mardy’s fiancé.

During Mardy’s college years, she had expressed little serious romantic interest in any of her male companions. But when friends introduced her to Olaus in 1921, Mardy was intrigued. “She was quite a looker, and she was turning suitors down,” explained Donald Murie. “She found my father mysterious, and it took a while for her to understand him.”

“We walked home together in the rosy northern evening; all I can remember is that we agreed we didn’t care to live in cities. He did not say: ‘When may I see you again?’ as all the rest of them did. He was not like any of the rest of them, and it took me quite a while to understand this,” wrote Mardy.

Shortly after Mardy’s graduation, Olaus returned from studying the caribou populations, and they married one early morning in 1924. Their marriage and the ensuing honeymoon—which included a steamer trip up the Koyukuk River and a dog sled ride through the untracked wildlands of some of the Alaskan Arctic— proved to be another turning point in Mardy’s life. She transitioned from a college girl to the wife of a researcher and quickly adapted to life in the backcountry. “I did not try to put my hair into its usual Elsie Ferguson puffed and rolled style, she wrote soon after her marriage. “I parted it in the middle and combed it into two long braids to hang over my shoulders; this was the way it would have to be for the coming months.

Together, the two began a life dedicated to the land, people, and wildlife they loved. Mardy served as Olaus’ constant companion and research assistant, helping document and catalog the information and specimens he collected. “They formed a partnership that went beyond marriage,” said her son, Donald. “Their work was number one in their lives. As children, we always kind of resented it. But it was something they had decided on before they married.”

In 1927, the Muries moved to Wyoming to study the largest elk herd in North America, which was dying mysteriously. Soon they were settled and raising three children in a place they grew to love almost as much as Alaska. “We first loved Jackson Hole,” Mardy wrote, “the matchless valley at the foot of the Teton Mountains in Wyoming, because it was like Alaska; then we grew to love it for itself and for its people.”

During the summer, Mardy and the children would often accompany Olaus into the hills and sagelands. The family set up camp and lived outdoors for many months, an experience that Mardy relished and found more liberating than summer in town. “Camp life suited me; it was just naturally no trouble for me to settle into it,” wrote Mardy. “Many women have asked me: ‘How did you manage the children way off there in the hills?’ Well, all I can say is that it was simpler there than in town. They were well fed, and because they were busy in the open air every moment, their appetites were wonderful; they grew and were brown and never had a sick moment that I can recall.”

“Mardy loved being outdoors,” said Shea, who has known Mardy for many years. “For her, it was freedom.”

Into the Spotlight

By 1937, Olaus had become a well-known and highly regarded naturalist—but he was also a disillusioned one. Tired of researching and writing reports that had little impact on the government’s policy toward habitat protection, Olaus accept a new position as director of the Wilderness Society. Soon he and Mardy were working with other key conservationists, including Howard Zahniser and Aldo Leopold, to promote environmental protection.

“We had become immersed in the conservation battle,” Mardy wrote, “and enthralled and stimulated by it and by the interesting people we met in connection with it, and we both knew that life was blooming, expanding, growing because of the new work Olaus had undertaken. It demanded a great deal of us both.”

The Muries threw themselves into their new work. But when Olaus died in 1963, just months before the passage of the Wilderness Act, Mardy was stricken. “She was always at his side,” said Donald Murie of his mother. In search of a new focus and purpose, Mardy traveled abroad to Africa and New Zealand with a friend. “After my father’s death, she didn’t know what she was going to do. But when she returned from her travels, she said ‘I have to continue. I need to do this for Olaus.’ She got more involved for him.”

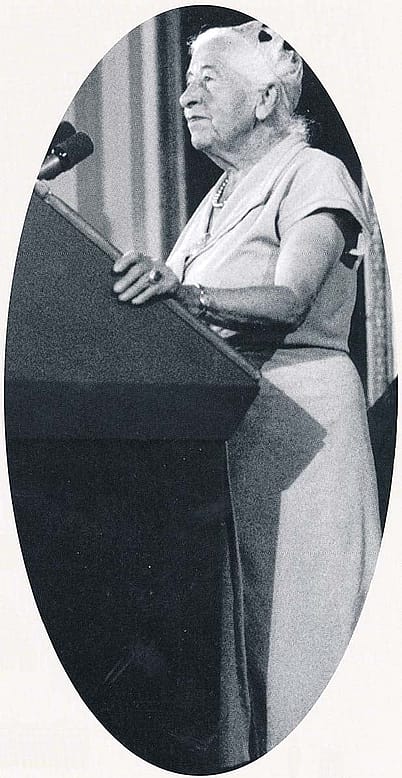

Thus emerged the “Fairy Godmother” in all her splendor. Mardy joined the Governing Council of the Wilderness Society, wrote articles and letters, lectured, lobbied, testified…and made her home a rest stop for scientists and a think tank for environmentalists passing through Wyoming. Her powerful presence and passionate vision had a dramatic impact on those she met and befriended. “I first met Mardy in the summer of 1973. I don’t remember many of the details, but I do remember seeing her and knowing instantly who she was,” said Bart Koehler, one of Mardy’s good friends who serves as director of the Wilderness Support Center in Durango, Colorado. “She was glowing.”

Mardy’s presence—and her ability to articulate her goals and values—made her an influential public spokesperson. “It’s hard to dismiss Mardy,” says Shea. “She was very clear about what was important yet her approach was so gracious and inclusive.” Part of Mardy’s ability to captivate her audience lay in her unapologetic appeal to the emotions. “Mardy knew that people don’t commit in the head.”

In her now famous congressional testimony on behalf of the Alaska Lands Act in the late 1970s, Mardy said:

I am testifying as an emotional woman and I would like to ask you, gentlemen, what’s wrong with emotion? Beauty is a resource in and of itself. Alaska must be allowed to be Alaska, that is her greatest economy. I hope the United States of America is not so rich that she can afford to let these wildernesses pass by, or so poor she cannot afford to keep them.

Mardy’s vivid writing also appealed to people’s emotions. Her words portrayed the potency, beauty, and value of nature; at the same time, she warned against the increasingly antagonist relationship between man and the wild. “It enlarges man’s soul to know there is wilderness, whether he ever goes there, or not… (But) we are too many; we are increasingly frustrated and bludgeoned by the civilization we have built,” wrote Mardy in the Living Wilderness magazine. “We increasingly flee to the wilderness, and we may kill the thing we love; we may trample it to death.”

Mardy’s lifelong crusade on behalf of the environment has earned her an abundance of awards. She received an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Alaska, the prestigious Audubon Medal, and the 1998 Presidential Medal of Freedom. In 2002, she was also honored with the National Wildlife Federation’s J.N. “Ding” Darling Conservationist of the Year award. The organization’s highest honor, the award is for a lifetime of achievement in the protection of wildlife and wild places.

Yet all of Mardy’s awards and medals do not ensure a secure future for America’s natural treasures. Oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, one of Mardy’s favorite places, has been a thorn in her side. “Mardy likes to get things done,” said Shea. “And for her, the Arctic Refuge is still not done.”

With more than a century behind her, Mardy can no longer continue the fight herself. But now there are others, the younger generations she and Olaus helped inspire, to maintain the momentum of the conservation movement. “She always spoke about what results she wanted to see and what we should be striving for,” said Murie. “She understood that it’s a fight that never ends.”

Ed. Note: Margaret “Mardy” Murie passed away December 19, 2003.

1. All quotes from Margaret Murie’s writings, unless otherwise noted, are taken from either Two in the Far North, written by herself, or Wapiti Wilderness, which she co-authored with her husband, Olaus Murie.

Post 301

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.