Will the Real Frontiersman Please Stand Up? – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2015

Will the Real Frontiersman Please Stand Up?

By Sandra K. Sagala

The controversy over the film The Interview (2014), in which North Korea leader Kim Jong-un was adversely portrayed, illustrates the potential danger filmmakers face when using a real person as a plot character.

The rendering of a well-known person’s life may be used as a vehicle for satire or comedy, but the avoidance of offense must be carefully balanced against the appeal to audiences. For an actor to portray a living person, with the possibility of a concomitant encounter, is nothing new. Two examples from nineteenth-century stage drama demonstrate the consequences of impersonating eccentric politicians and revered frontiersmen. Fortunately, these outcomes were positive.

Nimrod Wildfire and Davy Crockett

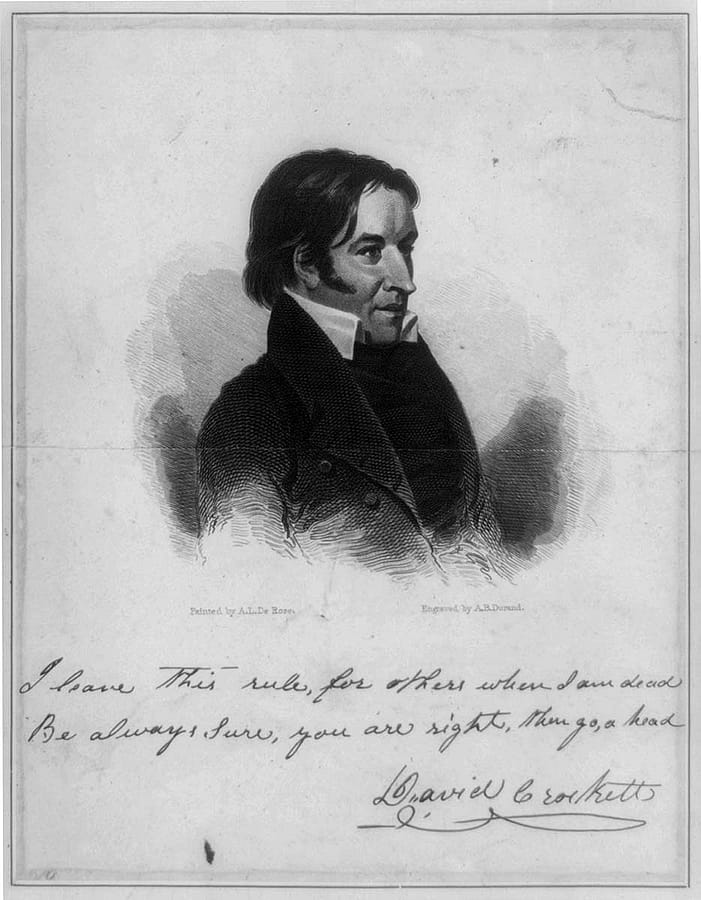

In 1831, actor James Hackett trod the boards of America’s theaters costumed in a buckskin suit and wildcat-skin cap. As Nimrod Wildfire, he caricatured the public’s perception of a Tennessee backwoodsman, specifically one of the most popular Tennessee backwoodsmen of the time, Congressman David Crockett.

The previous year, Hackett, accustomed to playing homegrown American characters like Rip Van Winkle, needed new material to showcase his talents. He sponsored a contest offering a $300 prize for an original comedy with an American as the leading character. Among those judging the entries were New York Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant and satirical poet Fitz-Greene Halleck.

James Kirke Paulding’s entry The Lion of the West; or, a Trip to Washington won top prize. Publicizing the winner, the December 18, 1830, issue of the New York Mirror praised Paulding’s “noble ambition to second the efforts of our indigenous comedian in laying the foundation for a national drama.”

No stranger to the topic, twelve years previously Paulding had penned The Backwoodsman, a poem glorifying frontier pioneers. He admired President Andrew Jackson and supported expansion of American settlement across the continent. Perhaps Paulding’s idea for the contest was politically motivated by Congressman Crockett’s vociferous objection to Jackson’s policies. One in particular, the controversial Indian Removal Act, forced Cherokees from their homes in order to give the land to the southern states. Crockett vowed that if the Act were not repealed, he would head for the “wildes of Texas.”

Though Crockett worked hard to represent his constituents, his policies against Indian resettlement were unpopular. Many Americans in the 1830s demeaned Indians and believed the Natives had no right to decide where they lived. Those who ridiculed Crockett’s use of picturesque and racy backwoods humor to make a point undermined his justifiable objections. In addition, he had not succumbed to the formal dress and manners of most Washington politicians; instead his folksy phrases and buckskin jacket sharply contrasted with his Congressional peers—idiosyncrasies that Paulding found irresistible.

The New York Mirror reported that Paulding found in Crockett the embodiment of “certain peculiar characteristics of the west in one single person, who should thus represent…the species.” Paulding wrote to his friend John Wesley Jarvis, a flamboyant portrait painter with a knack for Southern vernacular, and asked him for “a few sketches, short stories & incidents, of Kentucky or Tennessee manners, and especially some of their peculiar phrases & comparisons.” Paulding wasn’t fussy. If none came to mind, Jarvis could just “add, or invent a few ludicrous Scenes of Col. Crockett at Washington.”

The Lion of the West

Long before the drama’s opening night, rumor abounded that it lampooned Crockett and his backwoods mannerisms. Eager to avoid a suggestion of exploitation, despite that being exactly what it was, Paulding publicly denied such an intention in the Mirror. He also wrote to Congressman Richard Wilde asking Wilde to intercede with his fellow politicians to assure Crockett—”provided your knowledge of me will justify the assurance”—that he was “incapable of committing such an outrage on the feelings of any Gentleman.” Paulding enclosed a short note to Crockett reiterating his regret for the “mischievous and unfounded rumours” in the press.

Crockett replied that he had never seen publications to which Paulding referred. If he had, “I should not have taken the references to myself in exclusion of many who fill offices and who are as untaught as I am.” Instead, Crockett credited Paulding’s civility and guarantee that he had meant no mockery of “my peculiarities.” Furthermore, Crockett added, “the frankness of your letter…convince[s] me that you were incapable of wounding the feelings of a strainger [sic] and unlettered man who had never injured you.”

In the melodrama, the governor’s daughter, Cecilia Bramble, travels to Washington, DC, where she rashly falls in love with a Parisian count. She learns later he is an imposter and swindler. During a visit, Cecilia’s Kentucky cousin, Nimrod Wildfire, agrees to help expose the Count because, after all, he, Nimrod, can “jump higher, squat lower, dive deeper, stay under longer and come out drier” than just about anybody. When Wildfire challenges him to a duel, the Count bolts, but Wildfire unmasks the charlatan, and Cecelia regrets her impetuous behavior.

Despite Paulding’s protestations, Wildfire remained thinly disguised as Crockett, a backwoodsman who, in the play, claims to have “the prettiest sister, fastest horse, and ugliest dog in the deestrict.” Wildfire’s boasts of battling catfish the size of alligators as well as his having the ability to “outrun, outjump, throw down, drag out, and whip any man in all Kaintuck” were running exaggerations.

The play opened on April 25, 1831, at New York’s Park Theater. A review in the Mirror noted how the jokes were “really ludicrous,” thereby heartily pleasing the audience. But, after several performances, Hackett realized the script needed revisions. When Paulding refused the task, playwright John Augustus Stone rewrote the drama, keeping the Wildfire character and adding several others. Hackett toured the eastern states with the revised version.

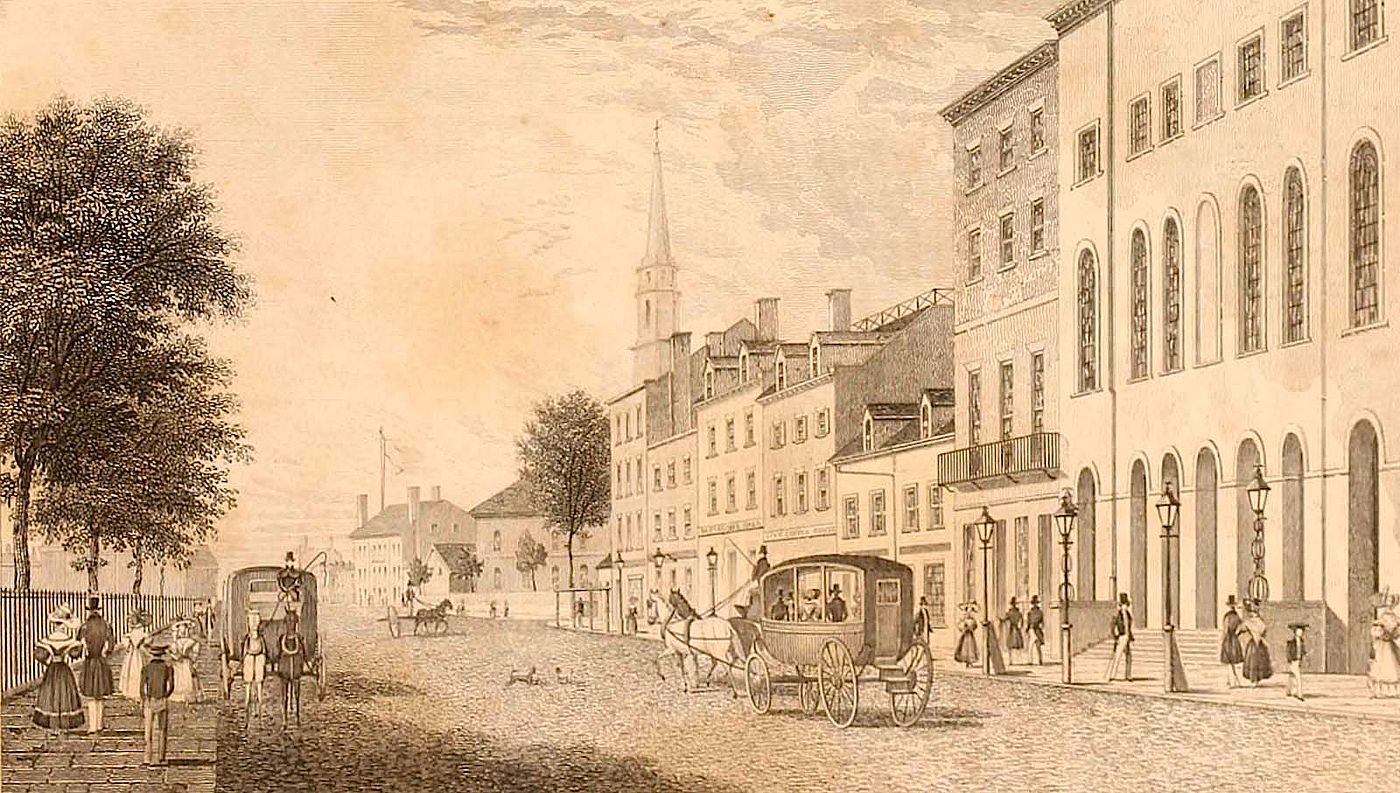

By December 1831, his tour reached Washington where Congressman Crockett himself took a front seat in the theater. When Hackett, costumed in buckskin, stepped onto the stage, he spotted Crockett and bowed to him. Crockett, in fancy theater-going clothes, stood and returned the bow, then acknowledged applause from the rest of the audience.

The play became the mainstay of Hackett’s repertoire for more than twenty years.

Conventional wisdom purports that history repeats itself. The confluence of drama and reality occurred with almost eerie similarity some forty years later.

Buffalo Bill and Ned Buntline

In February 1872, William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody visited New York City at the invitation of dime novelist Ned Buntline. The two had met previously at Fort McPherson, Nebraska, when the author had gone West in search of new material. At the time, Cody was a Fifth Cavalry scout. As the troops moved from fort to fort, Buntline accompanied them, all the while questioning Cody about his boyhood, his service during the Civil War, and his friendship with James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok.

The scout’s recollections supplied Buntline with ideas for a frontier hero. Six months after he returned to New York, Buntline’s Buffalo Bill, The King of Border Men—”the wildest and truest story I ever wrote”—was serialized in the New York Weekly. Editors proclaimed it “one of the most thrilling, exciting and interesting romances which we have ever read…its chief attraction is that its hero is not a myth, but a real flesh and blood character, who is even now fighting the savages on the western plains.” Overnight, Cody became a national hero.

Three years after its publication, New York playwright Fred G. Maeder dramatized Buntline’s story. The plot revolved around the murder of young Cody’s father by renegade Jake McKanlass. (The name was a perversion of Dave McCanles, whose murder at Rock Creek Station was attributed to Hickok.) When Bill Cody grows up, he, with his friend Bill “Hitchcock,” seeks revenge for the patricide. In turn, Cody rescues his mother and sisters from kidnapping renegades and their Indian cohorts. Popular actor John B. Studley was hired to play the title role.

Perhaps aware of and hoping to re-create a similar Hackett/Crockett encounter, Buntline insisted that Cody attend the performance and arranged for a seat in the manager’s box. Cody agreed, “curious to see how I would look when represented by some one else.” Reporters had publicized Cody’s plan, so when he and Buntline arrived, they found the theater packed with spectators hoping to glimpse the famous frontiersman.

The manager insisted that Cody come onto the stage between acts, meet Studley, and say a few words to the crowd. Cody was embarrassed, having never before been in the public eye. He later admitted that “a few words escaped me, but what they were I could not for the life of me tell, nor could any one else in the house.” His mumblings were scarcely audible even to the orchestra.

Veteran thespian Studley, undaunted at being upstaged by Cody, but doubtless infected by the crowd’s enthusiasm, “played his part to perfection,” according to the New York Herald. Critics found that Studley acted “in an intense, vigorous and powerful manner.” They judged the play “full of stirring interest, and if not critically a very meritorious composition, yet fully atones for lack of literary excellence by the picturesque interest of its incidents.”

Undeterred at impersonating the real frontiersman whose popularity continued to grow, Studley played the character for four weeks. William Whalley assumed the role when a prior commitment forced Studley to step down. Various versions of the drama played at other theaters throughout the city where it was pronounced “the hit of the season.”

Cody, the scout who had stood tongue-tied before that February audience, earned the similar distinction of “hit” only eighteen months later. By then, he had, at Buntline’s urging, begun his own theatrical troupe and starred in the production bearing his name.

Such juxtapositions of drama and reality, whether as serendipitous or pre-arranged meetings between the dramatic personae and the real frontiersmen, enhanced the celebrity of both David Crockett and William Cody. Dramas like these also helped to chronicle the frontier—be it located as far west as Kansas or as near as Kentucky—for eastern audiences.

About the author

Sandy Sagala is currently a member of the Papers of William F. Cody Editorial Consultative Board and has contributed several stories to Points West. She has authored Buffalo Bill on the Silver Screen: the Films of William F. Cody, 2013; Buffalo Bill on Stage, 2008; Buffalo Bill, Actor: a Chronicle of Cody’s Theatrical Career, 2002; and co-authored Alias Smith and Jones: the Story of Two Pretty Good Bad Men, 2005. She lives in Erie, Pennsylvania.

Post 302

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.