Forging an American Identity: The Art of William Ranney – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2006

Forging an American Identity: The Art of William Ranney

By Sarah E. Boehme, PhD

Former Curator, Whitney Western Art Museum

A boat, overloaded with men, floats on a river between two lush and green riverbanks. Several of the men sit on horseback and wear American Revolutionary War uniforms. An African-American man pulls the oar on the near side of the barge-like boat to propel it to the shore, while men talk and tend to their horses, in this scene with a myriad of interesting interactions and narrative details. The frontier-style garb of some of the men might link them to western types, but the verdant setting and the Revolutionary War era clothing locate this painting in another place and time than the American West of the nineteenth century that is usually the focus of the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West].

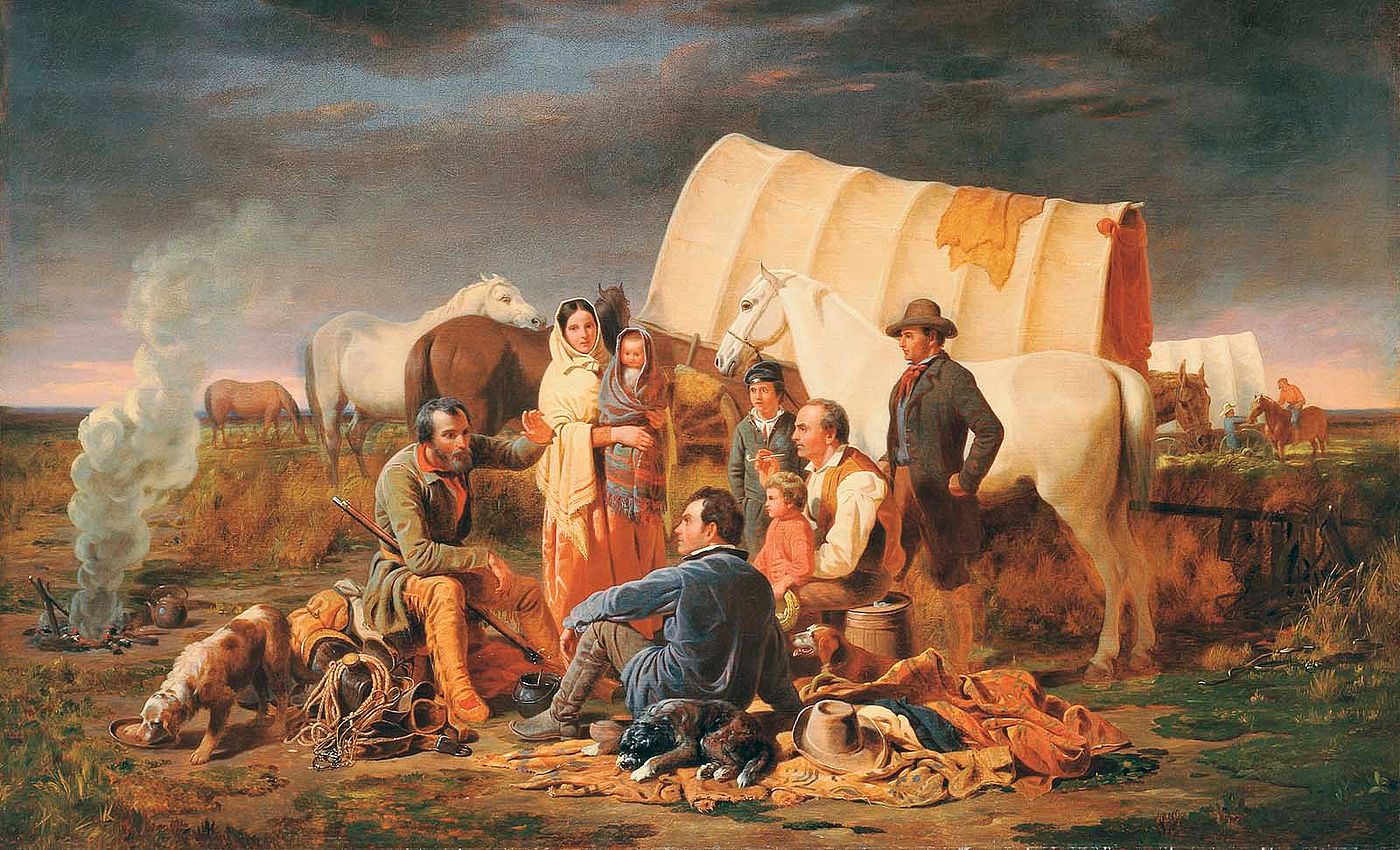

This masterwork, Marion Crossing the Pedee (from the collection of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art) joined other paintings with southern and eastern subjects, such as Virginia Wedding and First Fish of the Season, along with western classics such as Advice on the Prairie, as key elements of the Center’s special exhibition in 2006, Forging an American Identity: The Art of William Ranney.

Two factors link these paintings: They come from the hand of one artist, William Ranney, and they provide insight into the American identity. The exhibition gave the Center an opportunity to explore one artist in depth and to see how his paintings, sometimes disparate in subject, have an ultimate unity.

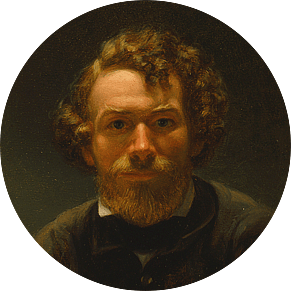

Ranney’s paintings of western scenes are some of his best-known works. They provide an anchor for his entire career, but are only one part of his subject matter. The exhibition gave viewers a presentation of the West in a larger American context, with selections of the artist’s different subjects. It included portraiture such as his own small but thoughtfully portrayed “Self-Portrait”; history paintings such as heroic evocation of Marion Crossing the Pedee; and genre (everyday life) scenes such as the delightful narrative of Virginia Wedding. Also included were Ranney’s sporting pictures, such as the luminous, but also humorous, First Fish of the Season, as well as the western images, such as the masterful interpretation of the western experience, Advice on the Prairie.

With 60 works of art, Forging an American Identity presented a more complete presentation of the artist than prior exhibitions that have featured his work. Visitors to Forging an American Identity had an extraordinary opportunity to see works of art loaned from public and private collections across the nation. The first comprehensive exhibition of Ranney’s art in over 40 years, the project included paintings that rarely travel and some that had been newly re-discovered. Backed by intensive research on the history of Ranney’s paintings and his career, the exhibition presented new insights into the meaning and interpretation of his art.

Contemplating powerful works such as Marion Crossing the Pedee and Advice on the Prairie, one might wonder why artist William Ranney is less well-known than some of his contemporaries or other western artists. One contributing factor is Ranney’s short lifespan and, consequently, his resulting comparatively smaller oeuvre, or body of work.

William Ranney was born in Middletown, Connecticut, on May 9, 1813, to Captain William and Clarissa Gaylord Ranney. The artist’s father, a ship captain, was often on voyages and was lost at sea in 1829. At age 13, the future artist was sent to live with an uncle in Fayetteville, North Carolina. While apprenticed to a tinsmith, Ranney began to develop his artistic interest. Six years later he moved to New York where he studied painting and drawing and began to establish a career. In early 1836, Ranney departed to become a volunteer in the war for Texas independence. This experience would become the reference for his later western scenes. He returned to the New York area in 1837 and began to submit pieces to the National Academy of Design and then the American Art-Union. His paintings of American life, with their strong narratives, were especially appropriate for the Art-Union.

In 1848 Ranney married Margaret Agnes O’Sullivan (1819–1903), who had immigrated to the United States from Ireland, and the couple settled in Weehawken, New Jersey, where their first son, William, was born in 1850. Their second son, James Joseph, was born three years later after they moved to West Hoboken, New Jersey, which would become the family’s permanent home.

A West Hoboken residence was close enough to New York City for Ranney to continue to have access to the exhibitions and art market. On the other hand, it was rural enough to provide land for his home and studio and for access to outdoor activities such as hunting, which the artist appeared to have enjoyed. Ranney outfitted his painter’s studio with western gear which attracted the attention of critic Henry Tuckerman, who described it as having “guns, pistols and cutlasses hung on the walls; and these, with curious saddles and primitive riding gear, might lead a visitor to imagine he had entered a pioneer’s cabin or border chieftain’s hut.”

In this studio Ranney created many of his most important works; however, his life and career were cut short by illness. William Ranney died November 18, 1857, at his home in Hoboken, New Jersey, of what was then called “consumption” and is today generally described as tuberculosis.

In his brief lifetime Ranney produced about 150 paintings. A catalogue raisonné, a publication which documents the known works of art by a particular artist, accompanied the exhibition. Scholars Linda Bantel and Peter Hassrick catalogued and analyzed the paintings, providing the context for the interpretation in the exhibition.

Ranney’s history paintings often focus on the American Revolutionary War which provided the founding myths of the American character, especially emphasizing independence and daring. In Marion Crossing the Pedee, Ranney depicted one of the heroes of the Revolutionary War from the South, Francis Marion, known as the “Swamp Fox.” Bantel has explained that Ranney portrayed a hero known for his patriotism and brave cunning:

“Francis Marion (c. 1732–1795), a successful planter and Indian fighter, was the South’s most famous Revolutionary War hero for good reason. When the British gained control of the South after the fall of Charleston in 1780, he was one of the few officers of the Continental Army left in the area who had not been captured, and he took it upon himself to organize and lead small ragtag groups of patriots. These self-supporting bands of guerrilla fighters tormented and harassed the British with midnight raids and hit-and-run tactics…”

Ranney painted not a battle, but created a made-up scene of the river crossing, which provides a space to portray, in close proximity, a wide range of types from the officers to the common men. Pointing to the prominence of two African-Americans in the painting, Bantel also speculates that the painting might be “interpreted not merely as a celebration of the American Revolution, but as a poignant visualization of the controversy sweeping the nation at the time Ranney conceived the picture: whether the newly annexed western territories should or should not allow slavery.” By depicting a river crossing, Ranney envisioned his heroic figures as moving across the American landscape, a theme he portrayed in his paintings about the American West.

Advice on the Prairie can be seen as a straightforward story of western travelers: a frontiersman providing counsel to an extended family crossing the American prairies. Peter Hassrick also found that the painting reflects on the nature of advice, which can be especially important in attempting journeys into territory that is not well known. He noted the religious overtones and connection to the concept of Manifest Destiny, “The family in Ranney’s painting provides a pictorial embodiment of the supposed sanctity of expansion. It is not just an American family; it is the metaphorical Holy Family on its way to the Promised Land.”

It seems apparent, then, that Advice on the Prairie becomes not only a description of common events, but takes on the significance of Ranney’s history paintings. The artist’s Revolutionary War painting highlighted a named hero, General Francis Marion, while including the anonymous volunteers who served with him. Advice on the Prairie and many of Ranney’s other western works focus on the unnamed figures of history, thus asserting the importance of the average person in developing the nation and its identity. Ranney’s paintings convey important concepts about American character through his dramatic visualizations, and this special exhibition explored those ideas with an unparalleled gathering of the artist’s most significant paintings.

Forging an American Identity: The Art of William Ranney was supported in part by the Henry Luce Foundation, 1957 Charity Foundation, Mrs. J. Maxwell (Betty) Moran, Mr. Ranney Moran, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Wyoming Arts Council through funding from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Wyoming State Legislature.

About the author

Dr. Boehme served as the John S. Bugas Curator of the Whitney Western Art Museum until 2006, when she joined the staff of the Stark Museum of Art in Orange, Texas.

Post 303

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.