Finding Frank – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2016

Finding Frank

By Jennifer R. Henneman

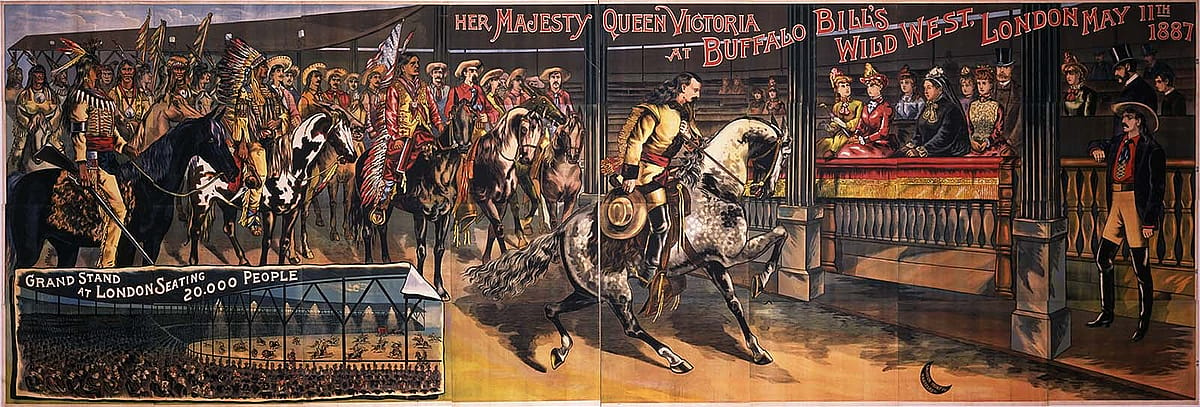

In a previous Points West Online article, readers took great delight in Mike Parker’s story about the Center of the West’s enormous 1888 Buffalo Bill’s Wild West poster featuring Queen Victoria (Fig. 1). A printer by trade, Parker wrote of the painstaking process to design the 10 x 28 ft. poster, let alone print it. Now, Jennifer Henneman studies the artwork of the poster—and the identity of one man in particular.

The human voice is the organ of the soul.

—Longfellow

Every accent, every emphasis, every modulation of voice, was so perfectly well turned and well placed, that, without being interested in the subject, one could not help being pleased with the discourse; a pleasure of much the same kind with that received from an excellent piece of music…

—Ben Franklin, speaking of an itinerant preacher.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West took London by storm during the summer of 1887 as part of the American Exhibition at Earls Court. Journalists relished the opportunity to report their impressions of performers and spectators alike. There were descriptions of Buffalo Bill’s excellent showmanship and elegant demeanor, and Annie Oakley’s extraordinary shooting and graceful hosting. Reporters noted Red Shirt’s wise words and noble bearing, and the British Royal family’s enthusiastic patronage. Frequently, the wonderful voice of orator Frank Richmond (Fig. 2) merited special attention.

Without recourse to any kind of vocal amplifier, Richmond narrated the spectacle twice daily to tens of thousands of attendees. This was a feat of vocal athleticism—particularly remarkable since his voice was not especially loud. One reporter noted: “Marvellous [sic] to relate, though no one could have believed it for an instant, every word of Mr. Frank Richmond’s comments was distinctly heard throughout the afternoon.”

After Richmond’s untimely death from typhoid fever while with the Wild West in Barcelona in January 1890, a number of published obituaries reiterated this amazement. One author stated that “for power and carrying qualities” his voice had “rarely, if ever, been equaled,” and another that his “clear, rich baritone, full and round, of great power and penetration” was heard by “thousands…[who were] struck with the ease and distinctness with which every syllable he uttered could be understood.”

Even medical experts turned their attention to the physiological curiosity of his voice. In 1887, the British Medical Journal published an examination of Richmond’s vocal cords conducted by Dr. Robert C. Myles of New York. The doctor found them of “ordinary length, and not much above the average in breadth.” Even so, Richmond’s vocal processes were extraordinarily well developed, allowing the laryngeal muscles “to act to the best advantage with a minimum of effort.” Further, his larynx was found to be quite large, his pharynx “exceptionally roomy,” and the “mucous membrane…remarkably free from granulations or roughness of any kind.” Ultimately, however, Dr. Myles concluded that the secret to Richmond’s delivery was his training as an actor and “the perfection with which he has learned to use his natural advantages.”

While the astonishing fact of Richmond’s voice persists in the historical record, his portrait does not. As a result, he remains a central, though strangely disembodied, figure within the history of the Wild West’s earliest European tours. However, documents with the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Papers of William F. Cody, as well as Annie Oakley scrapbooks at the McCracken Research Library also at the Center, suggest that since 1888, a representation of Frank Richmond has been standing confidently in a monumental Wild West poster—roughly 10 feet high by 28 feet wide. The Center’s Buffalo Bill Museum acquired the mammoth sign in 2014 and placed it on display behind an installation of a replica of William F. Cody’s tent.

A Herculean printing task

Created by Calhoun Printing of Hartford, Connecticut, Her Majesty Queen Victoria at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, London, May 11th 1887, celebrated the performance commanded by the Queen during the Wild West’s enormously successful 1887 London tour. Moving from left to right through the complex, horizontal composition, and embraced within the sweeping curve of the grandstand, the vivid colors and sharp-edged woodblock lines of this mighty feat of printing capture the event’s spectacular scenes.

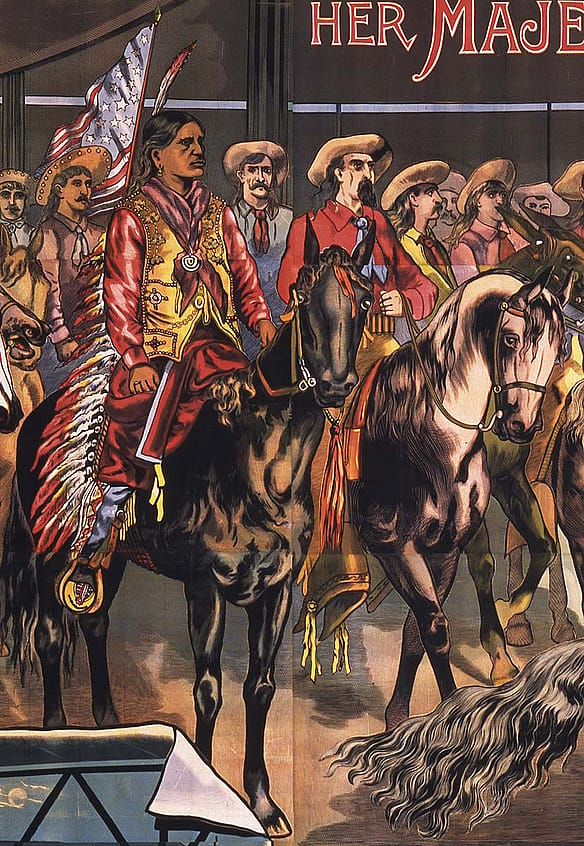

Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper described the “Mexicans in all the extravagance of velvet and silk; Indians painted and tattoed [sic] in every imaginable colour” and “cowboys in sashes and corduroy.” In particular, three mounted Native American figures—including Red Shirt on the right—were printed with particular attention to detail as seen in the minute delineation of beads, quills, feathers, and claws (Fig. 3). The rich color values used to depict their costumes and their horses—including the energetic tonal contrast of the central horse’s pinto markings—visually stabilize the foreground of the “picturesque line” of performers who “parade before her Majesty.”

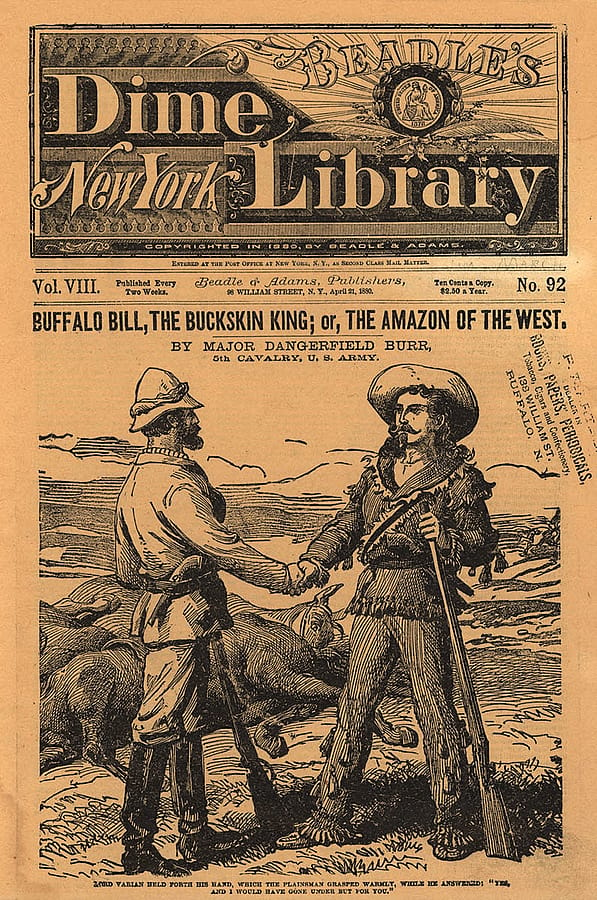

The composition portrays the moment at which, following the dramatic entrance of his troupe, Colonel Cody rides toward the Royal Box, backs “upon his graceful horse,” and “bows in front of [Queen Victoria].” Dressed in the fringed buckskin of the dime novel plainsman—a costume that references depictions such as that on the cover of Beadle & Adam’s Buffalo Bill, the Buckskin King or The Amazon of the West (Fig. 4)—Cody sits deeply in the saddle as he reins in his horse. His hat is swept off his head, and his hair and buckskin fringe flow behind. This genre of image would have been widely produced in the United States and Britain prior to Buffalo Bill’s appearance in London in 1887. Such images thereby rendered him a readily recognizable representative of a sensationalized American West.

This command performance took place at five o’clock in the afternoon; hence, bright daylight illuminates the faces and features of those within. In contrast, the inset vignette of the grandstand in the bottom left corner of the poster depicts the public attending an evening performance. Poster artists took pains to emphasize the notable degree of electric lighting that allowed the entire American Exhibition at Earls Court to remain open late. Above the illuminated arena in which various participants frolic, thin clouds swathe the full moon, and, along the upper left edge of the entire billboard, extinguished electric lights reflect the blue sky of midday.

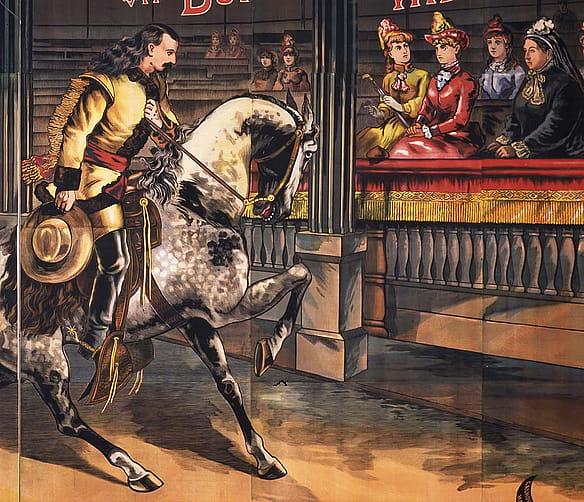

While Buffalo Bill shows gentlemanly deference in taking off his hat for the Queen, he remains upright and in powerful control of his steed. The artists leave no doubt regarding the literal and metaphorical centrality of Buffalo Bill’s image. The darkened shadow behind horse and rider push their figures forward. The color pop of Cody’s yellow buckskin and red sash further enhance this eye-catching ploy. Along a horizontal band of stacked vertical figures and static architecture, the body of Cody’s horse presents a dynamic diagonal line that starts from the point of its tail and juts upwards through its body, ending at the forceful point of its knee toward the Queen. Still dressed in mourning twenty-six years after the death of her husband, Prince Albert, Victoria is immediately recognizable by her black attire and stoic visage. Arranged along the same sight line, Cody and Queen Victoria stare into each other’s eyes (Fig. 5).

Who is that man in the red shirt?

The artists took some liberties regarding this particular interpretation of the event, even though they were probably working directly from news reports published immediately after the Queen’s visit. According to Parker, the preparation and execution of this poster may have taken upwards of a year—so production of the blocks could have feasibly begun during the 1887 London (May–October) tour.

For example, although the Washington Post reported that the Queen attended with about forty guests, the crowd depicted in the poster is decidedly smaller. Moreover, Edward, the Prince of Wales, and his wife Alexandra, shown to the Queen’s left, did not attend the May 11 command performance, although they appeared on other dates. The five other prominent female figures around the Queen, representing the “brilliantly attired fair ladies who formed a veritable parterre of living flowers around the temporary throne,” are unrecognizable (Fig. 6). Their standardized large eyes, straight noses, small mouths, and modish attire reduce them to the beautiful types found in mass-produced fashion plates, though viewers may have assumed that the two seated in the front row with the Queen represented Princesses Beatrice and Louise.

The other attendees, scattered throughout the arena, appear to be nothing more than visual space-fillers. Supposedly, the event was very tightly controlled, and the show’s management did not allow entry to the public. A group of detectives were apparently present, but “they occupied seats well down towards the right,” the Washington Post reported May 13, 1887.

In contrast to the tightly packed crowd within the arena, the right side of the composition feels strangely empty, occupied only by the primly seated British contingent, a scattered audience, the printing company’s black crescent-shaped logo, and a lone male figure leaning casually on the banister. Dressed akin to a Buffalo Bill dime novel alter ego in thigh-high boots, sombrero, tan trousers, a red laced-up shirt, blue neckerchief, black jacket, long brown hair, and well-trimmed mustache, this man’s appearance leaves no doubt as to his affiliation with the Wild West show.

That man in the lower right of the poster was formerly identified as Cody’s partner Nate Salsbury, but a comparison with contemporary photographs does not support this attribution. In an 1887 Wild West group portrait taken in front of the London arena backdrop (Fig. 7), Salsbury (Fig. 8) rests on the ground, his right arm behind his back and his left hand draped across his left knee holding a cigar. Salsbury’s fully bearded face and top hat contrast with the wide-brimmed hat, clean-shaven cheeks, and long hair of his partner Cody, who sits on Salsbury’s left gazing toward the right edge of the frame. The attention given by the poster’s creators to specific portraits of the most prominent figures—particularly Red Shirt, Cody, and Queen Victoria—suggests that, if this foregrounded figure were indeed Salsbury, they would have paid him equal deference in accurately depicting his likeness.

Primary sources support the argument that the standing man in the billboard is, in fact, our elusive Frank Richmond. Another possibility is that the figure represents tall cowboy Buck Taylor, especially considering his long hair and moustache. An account of the command performance relates, however, that Taylor was mounted during the performance, as would be expected, and that he “dashed up and saluted” the Queen while on horseback. The Washington Post reported:

Richmond, the orator, in a picturesque suit of buckskin and beadwork, with his long brown curls floating in the wind, stood just at the left of the Queen, outside the box, and called out in a clear musical voice an explanation of every item of the limited bill. Occasionally the Queen would turn to him and ask him some question.

While the description of Richmond’s clothes does not perfectly correspond, the placement of this figure in relation to the Queen does. This position is further supported by the Daily Telegraph: “The ‘orator’ was not called on to exercise his excellent powers of sonorous elocution from the rostrum, but stood just outside on the left of the Royal box and performed his duties of introducing the various groups.”

In its retelling of a public performance the day earlier, the Sportsman wrote that “a picturesque sombrero-crowned figure in the person of Mr. Frank Richmond did excellent duty as an animated programme,” and the author of an undated clipping from the Daily Telegraph reflected on the fact that Buffalo Bill and Richmond looked very similar: “Great was the speculation as to who Mr. Frank Richmond, the orator, could be. He had long hair—so has Buffalo Bill; he was fantastic in attire and headdress—so, according to the hoardings, was Buffalo Bill!” Physical descriptions given in his obituaries describe him as “a man of magnificent physique” whose rugged appearance lulled viewers into thinking he “had an iron constitution,” an assumption proved sadly wrong by his sudden death.

Is that really Frank?

Seemingly, Richmond has remained out of sight—though not out of mind—in the historical record. Nevertheless, the resurrection of important primary texts available in the collections of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, many of which are digitally available in the William F. Cody Archive, helps us regain an estimation of his appearance. The existing descriptions we have of the great orator corroborate the appearance of the tall sombrero-haloed billboard figure. In speaking on behalf of the Wild West, Richmond contributed to the powerful, multi-sensory spectacle that so firmly impressed audiences—including the representatives of the British Empire who sit bracketed between two incarnations of the western hero in this billboard.

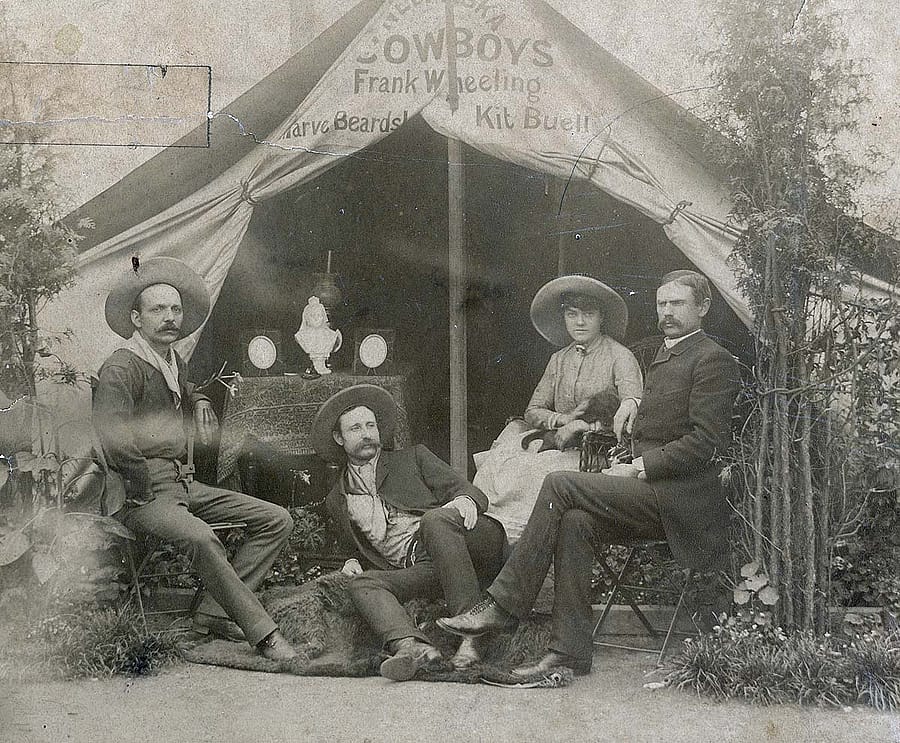

Queen Victoria herself reinforced Richmond’s centrality to the Wild West. At the culmination of her visit on May 11, she saved her final bow for “Orator Richmond, and then the carriage started and in a moment was out of sight,” reported the Washington Post. According to the Sun of New York, she later “presented him with a marble bust of herself in recognition of the pleasure he afforded her by his interesting description of the various features of the exhibition.” In an 1887 photograph (Fig. 9), one can see this bust placed prominently on a table in front of a cowboy tent gazing over the head of a currently unidentified reclining man with long mustache and sombrero. His purposeful placement in this staged photograph under the spatial aegis of such a valuable royal representation suggests that this man may indeed be our Richmond.

Although a convincing photographic identification remains elusive, we might nonetheless return to the 1887 group portrait and scan for a man whose body seems tall and broad, with a face sporting a dark mustache and long hair crowned by a wide-brimmed hat (Fig. 10). Our eyes might fall on a squinting man with laced-up shirt, seated cross-legged behind Cody’s daughter Arta on the left side of the photograph, with long moustache and loose tendrils of hair blowing past his hat: Have we finally found Frank Richmond?

About the author

Jennifer R. Henneman is a doctoral student in art history at the University of Washington in Seattle and completed a research fellowship with the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in summer 2015. She earned a master’s degree in art history at Richmond, the American International University in London, and studied studio art and French at Montana State University and L’Université Paul Valèry III in Montpellier, France. After Henneman receives her PhD in March 2016, she hopes to pursue a curatorial career and continue her research, which reflects her own upbringing on a Montana ranch and her interests in Victorian art and culture. She is particularly grateful for the insight and support of the McCracken Library and Cody Archive staff.

Post 305

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.