Beetle Buffet – Feeding on the Future of Science

Tucked away in aquarium tanks rifling through skulls and bones of a bull snake, wolf, and osprey are the dermestid beetles of the Center of the West. Though these quarter inch beetles have been a part of cleaning specimens for the Draper Natural History Museum for around 10 years, their home base has not always been as nice as their current set up. Living for stints in the garages of the Draper curators, the beetles most recent eviction from Nathan Doerr’s garage landed them in a shed on the Center of the West’s property. The space expansion has enabled the beetles to take on more specimens, cleaning an estimated 50 animals a year depending on availability.

Bring the Beet(les) In

“As a salvage- and transfer-based collection, partnerships with agencies and organizations are critical to our efforts in documenting life in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. These specimens end up in our natural history collection and are used for exhibition, scientific research, reference, and programming,” said Doerr.

Operating as a salvage and transfer collection, the Draper receives new specimens from the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, and local wildlife rehabilitators. As a part of this program, the Draper does not go out and acquire specimens. They receive them after an animal has reached the end of its life. This means that the dermestid beetles have a steady, varied stream of new specimens.

The recently acquired wildlife specimens will pass through the hands of dedicated volunteers or employees of the Draper. After the intake forms and freezer tags have been diligently filed, next comes the decision of how to move forward with the specimen. Depending on age, sex, injury, and other factors; a specimen can be mounted, turned into a study skin, or sent to the dermestarium to be skeletonized.

Before being sent to the beetles, a specimen will need the outer layer (skin, feathers, etc.) and major muscle groups removed. Visitors can view staff and volunteers preparing specimens on Tuesdays in the Draper lab from 9 a.m. – noon. When finished, the specimen is frozen until there is room on the menu in the dermestid beetle buffet.

Benefits of the Beetles

Saving volunteer time is another benefit of the dermestid beetles. While the beetles chomp away at the soft tissues, volunteers set in on the work the beetles cannot. After being cleaned by the beetles, bones are soaked in ammonia to degrease. Following this the skeleton is scraped for remaining residues or organic tissue. The skeleton is then soaked in hydrogen peroxide, to gently whiten the bones. Finally, the specimen is documented and catalogued before being sent to the vault to await its future utility.

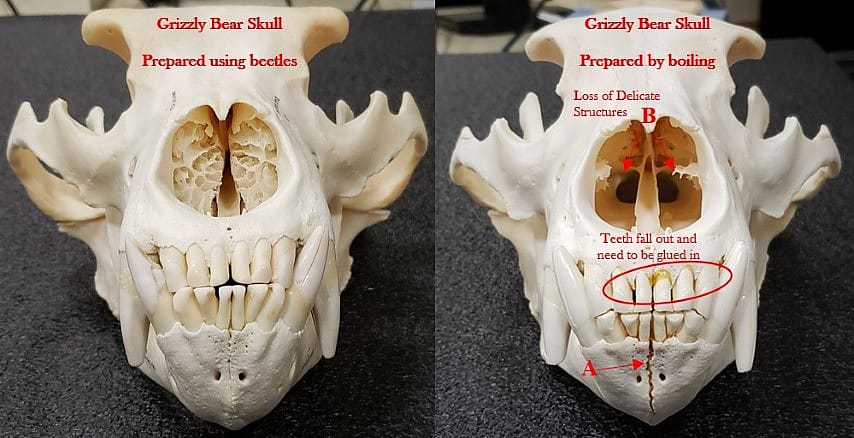

Another benefit to using beetles to clean skeletons is they help to maintain the scientific integrity of a specimen after treatment. A different cleaning method, boiling, often diminishes the quality of the finished project. When looking at a dermestid-cleaned grizzly skull and a boiled grizzly skull side by side, the beauty in the beetles’ work becomes apparent. The delicate internal features of the nasal cavity, sturdy teeth, and fused natural sutures of a dermestid-cleaned skull offer a perspective that is often lost in bubbling waters of a cleansing boil. By utilizing the beetles for delicate decimation, scientific structures remain intact for future study.

Making Sense of Skeletons

The litany of benefits from using dermestid beetles in turn offers a world of opportunity with cleaned specimens. Serving to preserve scientific integrity, the vault is filled with specimens ready to be studied and surveyed. For instance, assistant curator Corey Anco is comparing the skulls of post-reintroduction wolves of Yellowstone to those of pre-extirpation specimens housed in natural history museums across the country to determine if reintroduced wolves are larger than pre-extirpated wolves as rumors suggest.

Another practical utility falls to the museum floor, where the hope is to integrate articulated skeletons alongside full-body taxidermy mounts of the same species. The companion displays would help to demonstrate animal structure under the surface of fur or scales. Staging in this way combines bringing items out of the vault and furthering the knowledge shared with visitors. Looking at skeletons that demonstrate trauma which occurred in the animal’s life (healed or unhealed) could offer a new perspective on the relationship between injuries and environment.

What Does the Future Hold?

Resting on the backs of these little beetles is the opportunity for education and connection to the animals of the West for generations to come. The beetles do not shoulder all the burden though, as the dedicated volunteers and staff of the Draper work to clean, assemble, and maintain the specimens that come through as a result of nature taking its course.

“The volunteers, partnerships, and beetles are the driving forces of our collection,” Anco said as we stood watching beetles clean bones. Therein lies the beauty of the work necessary to preserve the Yellowstone ecosystem – it takes an ecosystem of its own.

Keep up with the happenings of the beetle bungalow and the Draper Natural History Museum through their blog. For a more in-depth look into the process of preservation at the Draper, take a look at Anco’s blog post on specimen preparation.

Written By

Genevieve Risner

Genevieve Risner is a PR and Marketing intern at the Center of the West. Most of her life has been spent honing the craft of storytelling, appreciating where that adventure takes her and who it connects her with along the way. In her free time, she enjoys crocheting, cooking, and exploring the charms of Cody, Wyoming.