Traveling West Page by Page – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall/Winter 2014

Traveling West Page by Page

By Henry M. Yaple

“To those with ears to hear, libraries are really very noisy places. On their shelves we hear the captured voices of the centuries-old conversation that makes up our civilization.” ~Timothy Healy (1923–1992), President of Georgetown University, and later, President of the New York Public Library.

As a volunteer for the McCracken Research Library at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Henry Yaple has been hearing voices. In 2013, he began cataloging the Charles G. Clarke Library of Western and California History. The set of books includes copies of the “Zamorano 80,” eighty titles selected by a group of West Coast book collectors in the 1940s as the most distinguished books about early California and its history (see sidebar at end). Little did Yaple know of the adventure in store for him when he opened that first treasured page….

The Emigrants Guide to Oregon and California

Zamorano 41 was one the first books I cataloged—Lansford W. Hastings’s The Emigrants Guide to Oregon and California. The first edition, an extremely rare book, appeared in 1845; the Book Club of California published the copy in hand in 1973. A quick perusal of the prefatory material revealed that while this emigrant guide was the first California guidebook, American citizens living in what was then the Oregon Territory also labeled it “a pack of lies.”

Hastings, it seems, earned the ire of Oregonians because he may have tried to divert Oregon-bound wagons to California. Worse, his suggested cutoff from the Oregon Trail—later named the “Hastings Cutoff”—led innocent settlers dangerously astray. The Donner party, a group of California-bound pioneers who became snowbound as a result and eventually lost half their number in the winter of 1846–1847, followed this particular cutoff to California. James Clyman, mountain man and wagon guide, told the Donner party not to follow this route. “It met difficulties in plenty on the way and [was] finally caught by snow in the Sierras.” What an insight into this infamous tragedy!

Death Valley in ’49 and History of the Donner Party

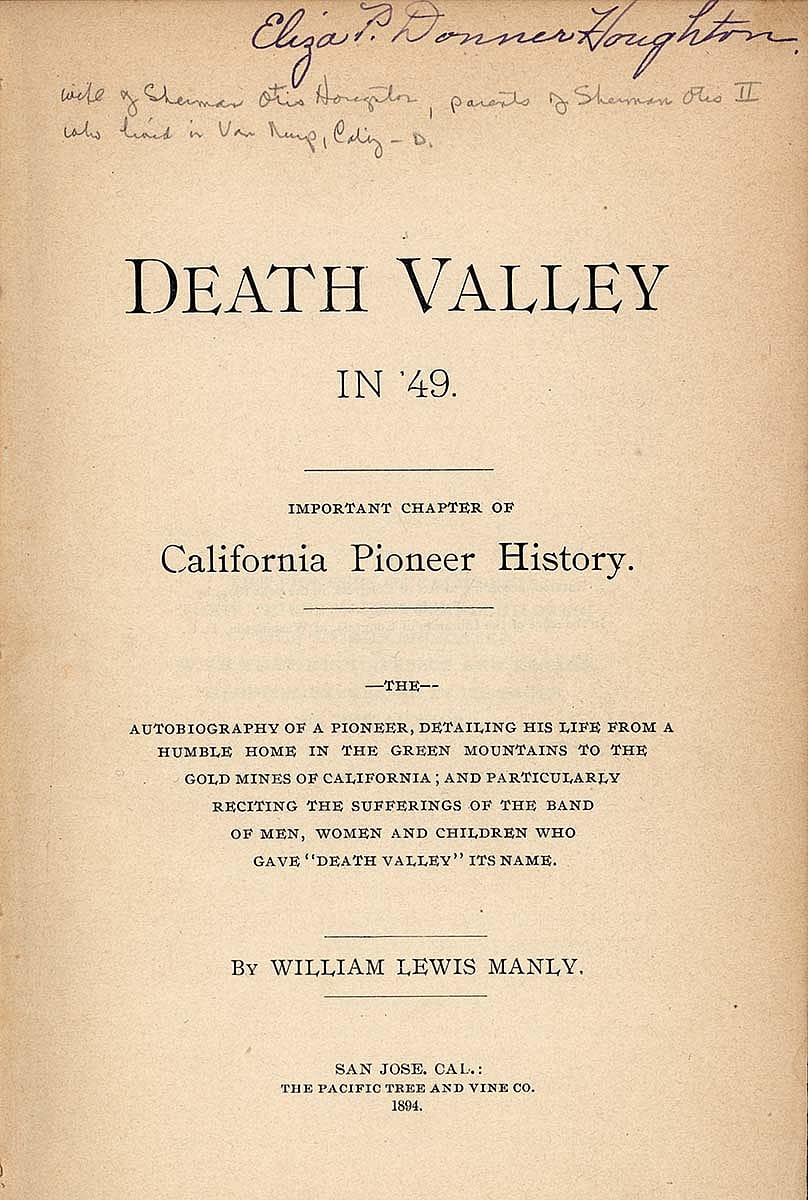

One of the next Clarke books was William Lewis Manly’s Death Valley in ’49 (San Jose, California: Pacific Tree & Vine Co., 1894) with a most informative subtitle:

An Important Chapter of California Pioneer History, The Autobiography of a Pioneer, Detailing his Life From a Humble Home in the Green Mountains to the Gold Mines of California; and particularly Reciting the Sufferings of the Band of Men, Women and Children Who Gave “Death Valley” Its Name.

Opening to the title page, I noted what appeared to be the owner’s signature, “Eliza P. Donner Houghton.” Wow! Could this book have been owned by a survivor of the Donner party?

Eliza Donner Houghton’s signature appears on the title page of William Lewis Manly’s “Death Valley in ’49,” 1894. McCracken Research Library Rare Books Collection.

Eliza Donner Houghton, from C.F. McGlashan’s “History of the Donner Party: A Tragedy of the Sierra,” 1880. McCracken Research Library Rare Books Collection.

Clarke’s prescient focus on collecting trail diaries and books germane to the history of California became apparent to me in just a few moments. In my stack of books awaiting cataloging, I spotted C.F. McGlashan’s History of the Donner Party: A Tragedy of the Sierra, San Francisco, California: Bancroft, 1880. Yes, Eliza Donner and her sister, Georgia, were daughters of George and Tamsen Donner. These two young women, indeed, survived the Donner Party’s horrible ordeal in the Sierra snows. No need to Wikipedia information here! Incidentally, Manly is No. 51, and McGlashan, No. 53, of the Zamorano 80.

Pigman and Baker: argonauts head home

Not every “argonaut,” as the westbound travelers were called, remained in California after their exhaustive cross-continental trek. Clarke’s copies of Walter Pigman’s The Journal of Walter Pigman, Mexico, Missouri, 1942, and Hozial Baker’s Overland Journal to Carson Valley & California, San Francisco, California—the Book Club of California, 1973—described their journeys across the plains to California, and their return home. After a relatively brief stay, each man left California via ship to Panama, crossed the Isthmus, boarded ships for New York, and then returned home.

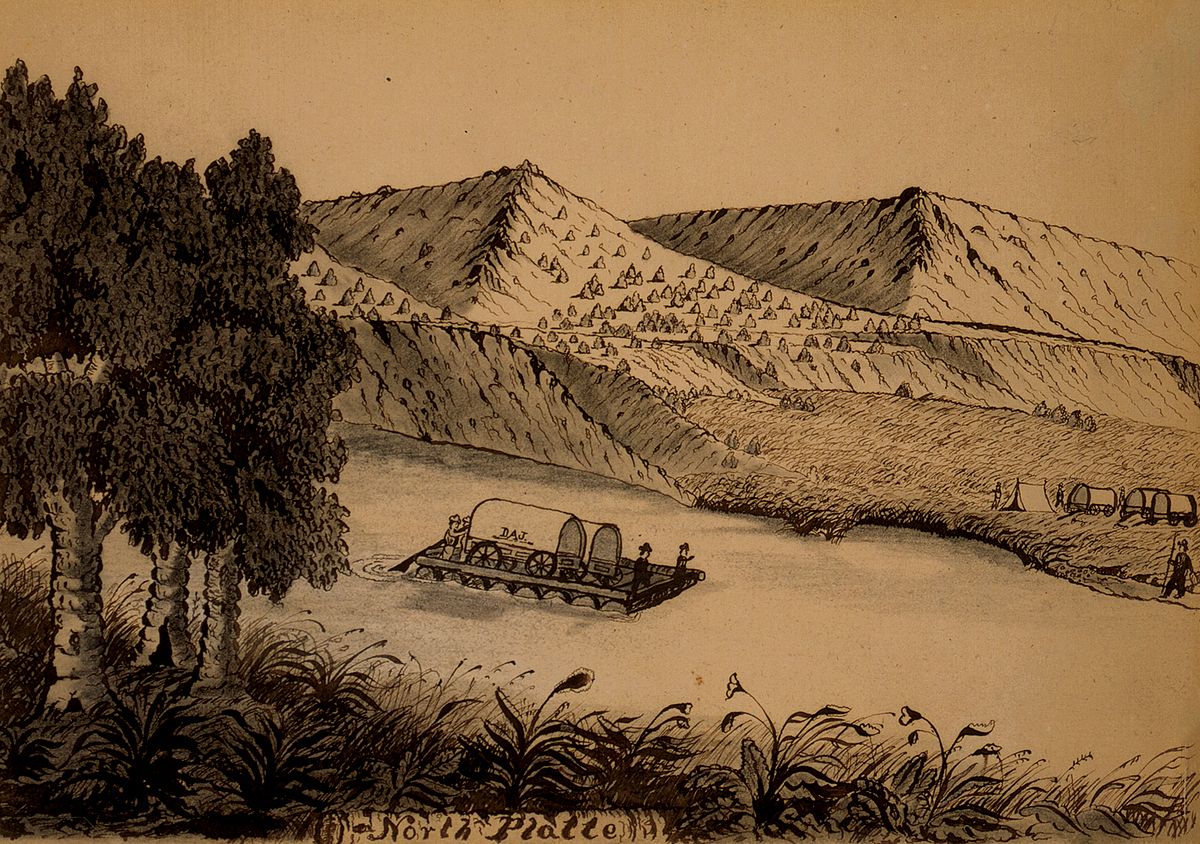

The decade separating their trips made some difference in their perceptions and observations. Both men stopped to climb Court House Rock. On May 16, 1850, Pigman wrote, “Four of us concluded to start early and visit the Court House Rock… walked 2 miles, ran two miles, gave out, rested and walked 4 miles farther and got to rock.” Left camp “without gun, pistol, or knife…wolves and bears unusually thick before we got in. None of us willing to leave wagons again to visit the like.”

Baker hiked the eight miles from the Oregon Trail to Court House Rock, climbed it, and inscribed his name below the summit, “H.H. Baker, May 7th, 1859. Aged 70 years.” No mention of bears and wolves, and he made the hike and climb entirely alone.

On May 12, 1859, Baker wrote, “I yet carry my little gun, my constant and almost sole companion. I now must travel on borrowed time; three score years and ten is man’s alotted [sic] time. No odds to me where I finish my course, so it is well finished. The little thrush is sweetly singing, the robin chirping. The mournig [sic] dove’s note is heard at a distance; how melancholy! Yet none so constant as the little lark. Day or night I hear its note. Traveled 18 miles.” As his chronological peer, I could only marvel at his tenacity, stamina, and courage.

Changes at Fort Laramie

The tenor of the times at Fort Laramie changed from 1850 to 1859, as noted from Pigman’s time there as compared to Baker’s. Pigman arrived May 19, 1850, at Fort Laramie. “After getting into camp, we took a walk up on the high bluffs to get a view of the Fort, and also the Rocky Mountains which we could plainly see covered with snow.” Major Sanderson, commandant, invited Pigman to dinner. Both men were natives of Ohio, and that may have elicited the invitation.

C.F. Smith, Journal of a Trip to California, 1850, arrived at Fort Laramie ten days later on May 29, 1850, and observed “500 wagons and 2,000 men near the fort.” He saw “one person taking a log chain, dragging it a bit, and leaving it on the supposition maybe it could be sold. Cling to things by force of habit. But must relinquish in face of distance and time.”

By the time Baker reached Fort Laramie, May 14, 1859, he “crossed the Laramie River on the bridge and paid $2.50, when by going a short distance could have forded. Garrison seemed bored and dejected.” The rush and bustle of the argonauts was gone.

Pigman noticed Laramie Peak “capped with snow while we are scorched with heat in the valley.” Baker did not mention the climate, but he described in some detail an incident on May 17, 1859, when William Beckwith’s horse was stolen, and there was much excitement and chasing about. Alone, Baker traced the missing horse’s hoof prints, tracked them, and found the horse—along with a second one—tied to trees. He recovered the horses, but departed so as not to get into a “scrape” with Indians.

Madame Adventure

Pigman traveled into California with relative ease, but ten years later, Baker nearly died of what we would probably recognize as hypothermia as he crossed the brutally cold, snowy Sierras. Upon arriving home, Pigman commented, “arrive 15 March toilsome journey of 5,000 miles made the trip home from San Francisco in 42 days.” At his homecoming, Baker stated, “I meeting my old citizen-friends who congratulate me upon my improved health and condition. My circuitous route from Seneca Falls to Seneca Falls again by railroad, over the plains, mountains, etc. and by steamer is 9,111 miles.” Ferol Egan, editor of Baker’s modern edition, commented, “A rare man for any season, he headed west on a young man’s journey in the twilight of his years.” One “can only have admiration for this courageous elder citizen who had a last dance with Madame Adventure and returned home to tell about it.”

My time with the Charles Clarke Library was not extensive, but it was clear he read his books actively and thoughtfully. In many of his copies of the trail diaries, he listed the names of each member of that wagon party on the fore leaf. My great grandfather trekked to California in 1852 seeking gold; that made each opportunity to catalog one of Clarke’s California trail diaries particularly poignant as I checked to see if one Wilson Macdonaugh Spencer appeared. Alas, that name did not.

The Clarke books experienced their own adventures before they came to the McCracken: They survived two California earthquakes. The damage they sustained required a certain amount of technical conservation work before readers could use them. Clarke’s daughter Mary Hiestand continues to support professional conservation of her father’s books so that the Charles G. Clarke Library is now available for readers and researchers at the McCracken Research Library of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

Sidebar: Rare Privileges

Mary Robinson, [now-retired] Housel Director of the McCracken Research Library at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, welcomed me as a volunteer in October 2013. When she learned that I had always enjoyed working with rare books as an academic librarian, she pointed out that the McCracken had many rare books to catalog. Though I had not cataloged a single book since library school some thirty years ago, then-Lead Cataloger Karling Abernathy began to teach me the finer points of copy cataloging. Our immediate task was to catalog the very rich western Americana library collected by the late Charles G. Clarke of Hollywood, California, and donated to the Center by his daughter Mary Hiestand.

Charles Clarke (1899–1983) lived an extraordinary life. He was born in California, and his mother passed away when he was only a boy. His father did not permit him to enroll in high school after he completed grade school. Instead, the father put young Clarke to work with a mule and plow to break sagebrush flats for cultivation. Not surprisingly, father and son did not agree.

Clarke left home at age 13 to make his way in Los Angeles. By 1915, (age 16), he began to work full time as a cameraman in the nascent Hollywood film industry. One of his early employers was Samuel Goldfish; later, this Samuel became well known as Sam Goldwyn. Clarke worked for five decades as a cameraman and cinematographer. His list of film credits is extensive and includes such titles as Whispering Smith, 1926; Tarzan the Ape Man, 1932; Mutiny on the Bounty, 1935; The Grapes of Wrath, 1940; Green Grass of Wyoming, 1948; and The Snows of Kilimanjaro, 1952.

In addition to his very busy film career, Clarke found time to write two books and see them published. His Men of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: A Biographical Roster of the Fifty-one Members and a Complete Diary of Their Activities From All Known Sources was published by Arthur H. Clarke in 1970. Clarke’s autobiography, Highlights and Shadows: The Memoirs of a Hollywood Camera Man, was published by Scarecrow Press, in 1989.

Mary Robinson pointed out that the Clarke collection was especially rich in Oregon Trail and Overland Trail diaries, as well as one copy each of the celebrated “Zamorano 80.” The Zamorano Club of Los Angeles, California, compiled this list of 80 books because the members, primarily wealthy book collectors, wished to identify the most “distinguished” books on the very early history and development of California. After some years of debate among themselves, they published this list in 1945.

These titles in their first editions turned out to be devilishly difficult to collect because of their importance and rarity. Indeed, only four men, Thomas Streeter, Frederic Bienecke, Henry Clifford, and Daniel Volkman, were able to collect each of these 80 titles in their first editions. Clarke did not collect these 80 titles in their first editions, but he was careful to acquire a copy of each one in good, modern editions. As I worked, the Clarke books made it apparent that Hiestand’s generosity and her father’s informed, prescient book collecting combined to make a munificent addition to McCracken’s holdings in western American history. ~Henry Yaple

Post 318

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.