The One that Got Away… A Photo, That Is – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2016

The One that Got Away… A Photo, That Is

By Tom F. Cunningham

The ways in which our Points West authors are inspired, driven, and influenced—and sometimes discouraged and disheartened—are often stories in themselves. In this case, Tom F. Cunningham shares the incredible story of the day that he first saw the Thomas Lindsay photographs that he includes in his story of the Wild West in Glasgow (click here to read it).

He also describes “the one that got away”—a photo, that is…

In 1991, I joined a group based in Glasgow, Scotland, called the North American Indian Association (NAIA). A short while after I became involved, NAIA ran a small but excellent exhibition in the Mitchell Library, Clans and Tribes. It celebrated various connections between Scotland and the Native Americans, almost none of which I had previously known.

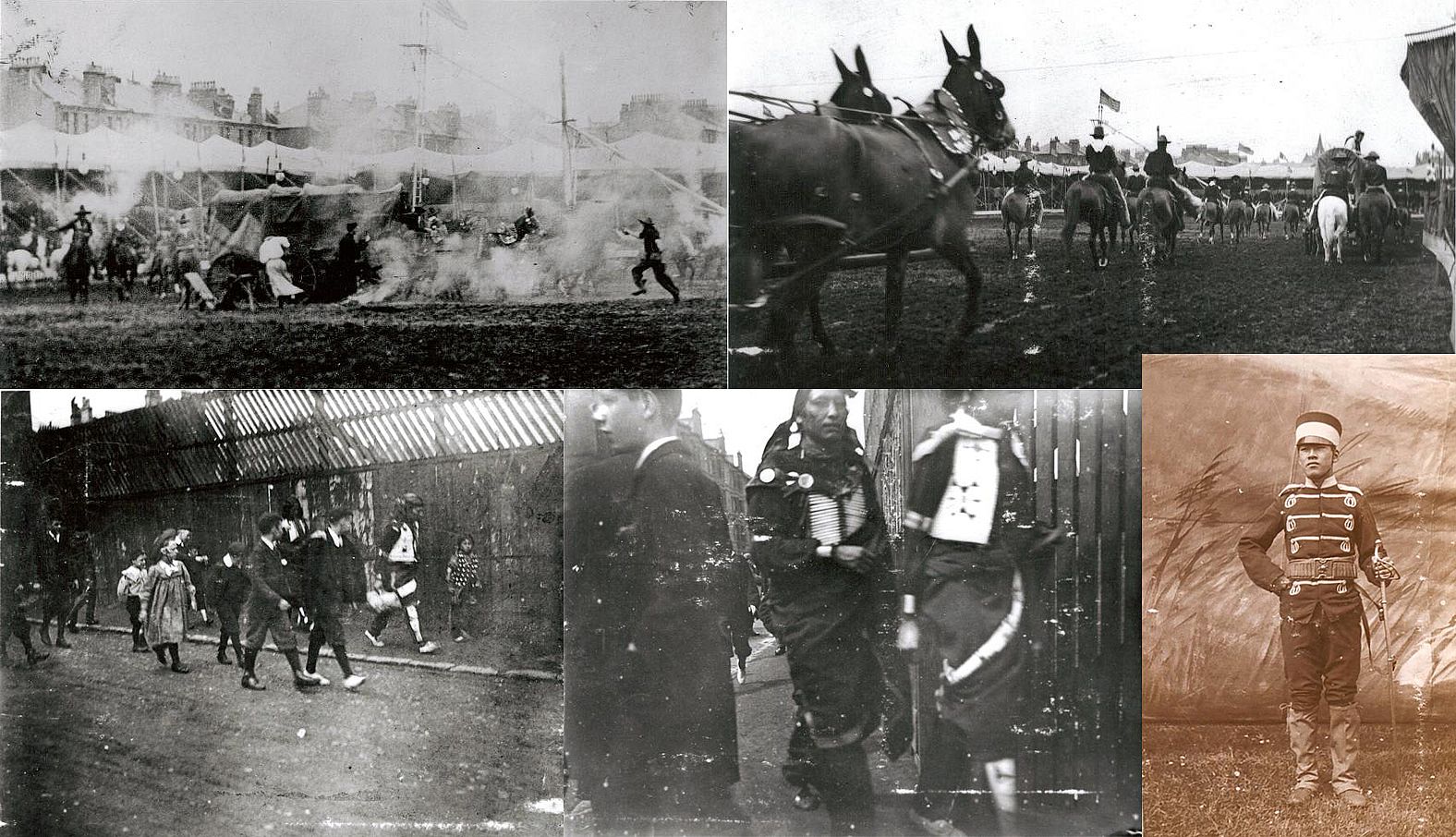

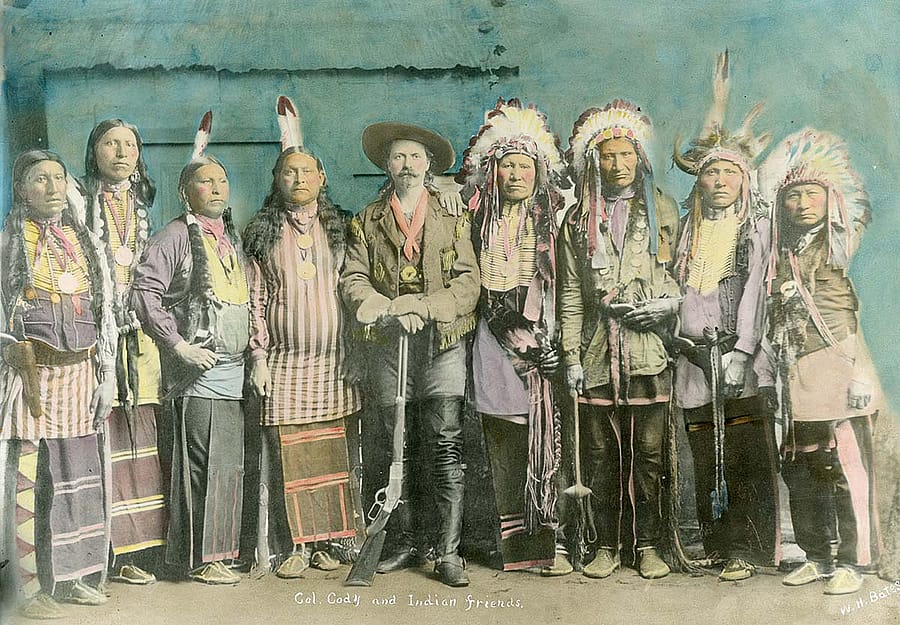

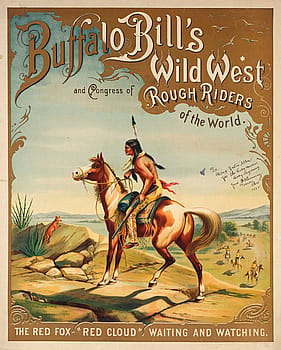

One of the themes was two visits to Scotland by Buffalo Bill Cody. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West played a winter season at the East End Industrial Exhibition Buildings in Dennistoun, 1891–1892. It returned to the South Side of the city as Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World for the first week of August 1904, a story shared in this previous Points West Online post.

It was in connection with Clans and Tribes that I had a meeting around 1992 with Director Barrie Cox in the basement canteen of the Mitchell Library. Also present was another man, whom I was meeting for the first time, Barry Dubber.

Barry (as opposed to Barrie) was then working on a book about Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Scotland which, sadly, never saw the light of day. I later took up the baton, and my book Your Fathers the Ghosts—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Scotland was eventually published in 2007.

What made my first meeting with Barry Dubber so utterly memorable was that while the three of us were sitting at a table, engrossed in an animated and fascinating discussion, Barry coolly produced some photographs and spoke the words which have remained etched on my mind ever since: “I can show you these but I can’t tell you where I got them.”

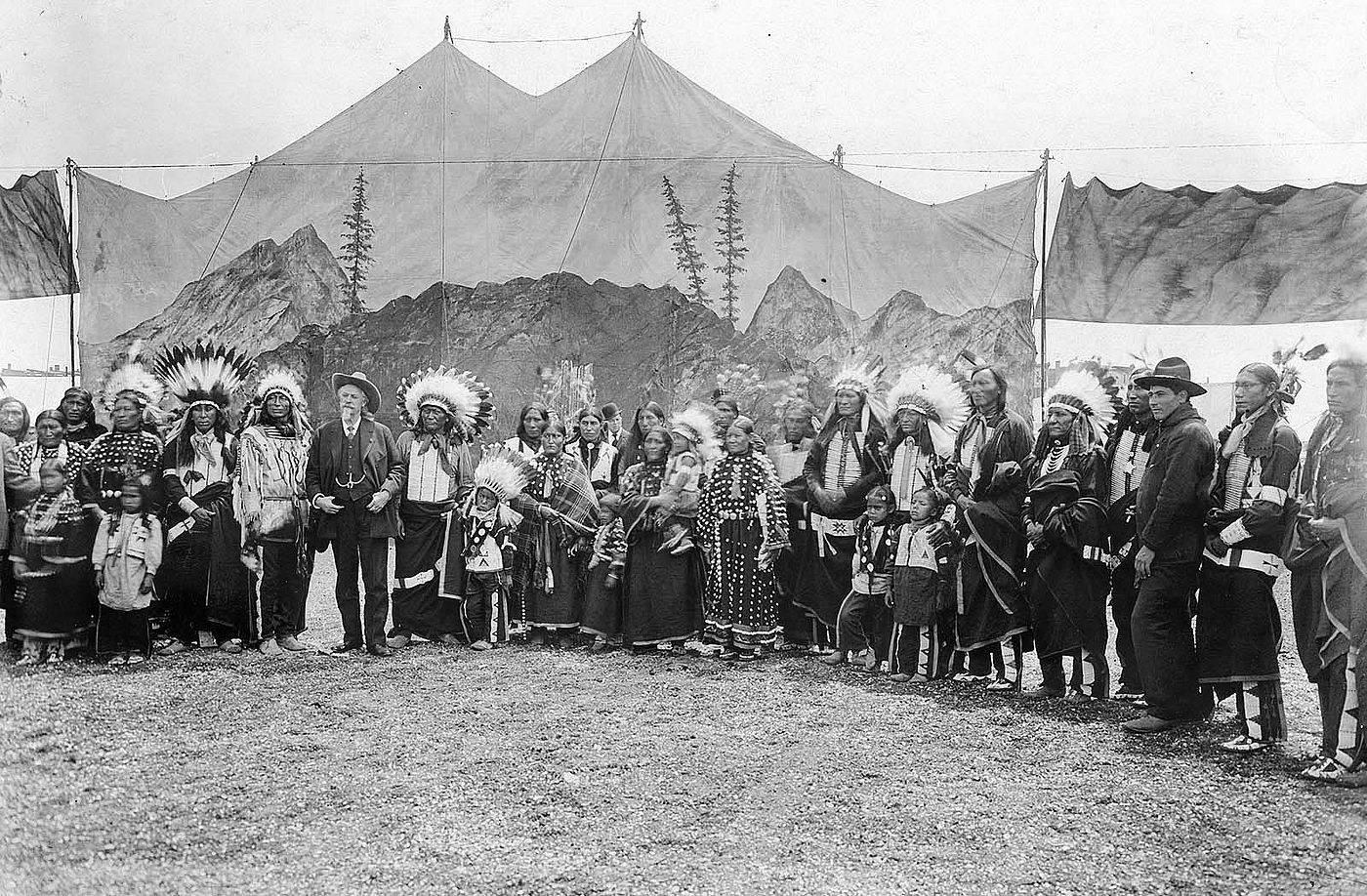

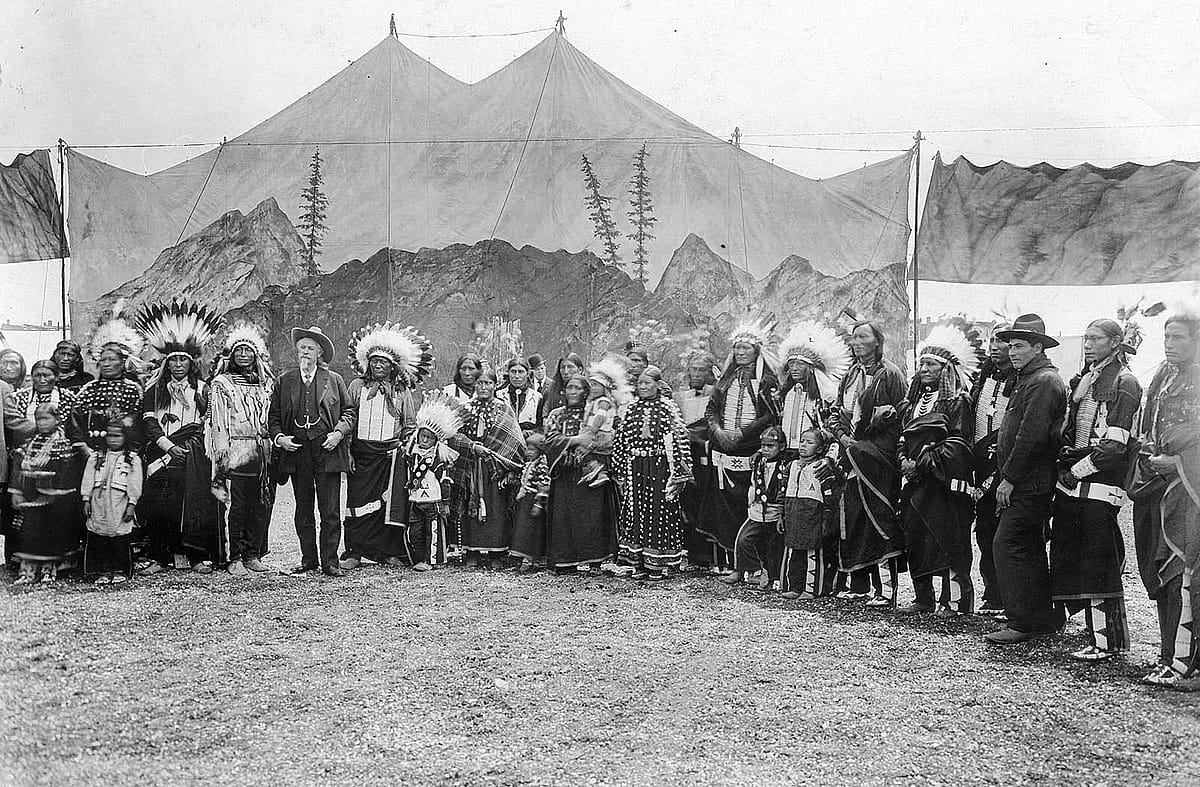

The images which he proceeded to display were of a mind-blowing nature, unlike anything I have seen before or since. Two of the photographs showed Indians (of the Lakota tribe, better known as Sioux) on Dixon Road, rubbing shoulders with the local people, who, given that this was Edwardian times, were interesting enough in themselves. Two other photos capture rare shots of the show actually in progress.

There are, of course, many photographs in existence of Buffalo Bill’s Indians, but the vast majority of these are by studio photographers and as such are heavily posed and even contrived. There is a fly-on-the-wall quality to the rare photos that Barry had of the Wild West in Scotland, taken by Thomas Lindsay. I have since realized that the images are very unusual and Lindsay was ahead of his time.

There was one particular image which stood out as truly sensational, even in the context of its illustrious companions. Sadly, this photo was later lost, and years after the event, Barry was unable to account for it. I can still see it in my mind’s eye, and if only I could draw, I would sketch it for you now. It depicted an Indian, with feathers and bone breastplate, standing on a street corner. The expression on his face was aloof, distant, like the impassiveness you sometimes see on the face of a famous footballer in the midst of a crowd. Even removing the human figures from the picture, it would still be an engrossing record of times gone by. The background was composed of tenements and a factory chimney, which I have since realized was probably Dixon’s Blazes.

What really made the image for me though was not even the Indian, but two local boys standing gazing at the apparition with looks of utter amazement. One, who had either forgotten his manners or else had none, was pointing straight at the Indian, who all the while was vainly trying to look inconspicuous.

I have been researching the subject more or less uninterruptedly since, and have amassed huge amounts of information together with an impressive collection of photographs. However, I hadn’t come across anything quite as astonishing as Barry’s photograph of the Lakota Indian on the Glasgow street corner. Neither have I given up hope entirely that another copy exists somewhere and that one day I might set eyes upon it once again.

That missing photograph sums up everything my work is about—I never ever set out to write exclusively about Buffalo Bill’s Indians. I have always been anxious to set these exotic visitors within the context of the times and to retrieve what I can about the local people with whom they came in contact. That photo brilliantly encapsulates this dualism, bringing together, as it does, both sides of the equation.

Seeing that photograph was a coup de foudre moment for me, which completely changed the whole course of my life. I have since written three books and countless articles on this and related subjects.

I’ve never been much of a fan of the popular musical group U2, but their song I Still Haven’t Found What I’ve Been Looking For keeps playing in my head!

About the author

A Scottish resident, Tom F. Cunningham is a graduate of Glasgow University in Scotland. For the past two decades, he has pursued an intensive study of Native American history with particular emphasis on connections to Scotland. He is the author of The Diamond’s Ace—Scotland and the Native Americans and Your Fathers the Ghosts—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Scotland. He also manages the Scottish National Buffalo Bill Archive, www.snbba.co.uk.

Post 320

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.