Meet Me in St. Louis – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2010

Meet Me in St. Louis

By Robert V. Goss

A previous Points West Online series featured the travels of Guy Gertsch, a man who walked the Lewis and Clark route to commemorate its two-hundredth anniversary. Another post featured artist Charles Fritz’s paintings of the Corps of Discovery, created as he, too, followed the trail. In this post, historian Bob Goss shares the story of two men from Cody, Wyoming, who followed the route—by water.

Rivers must have been the guides which conducted the footsteps of the first travelers. They are the constant lure, when they flow by our doors, to distant enterprise and adventure, and, by a natural impulse, the dwellers on their banks will at length accompany their currents to the lowlands of the globe, or explore at their invitation the interior of continents. – Henry David Thoreau

Long ere the shining rails of steel captured the noisy, smoking locomotives that followed them, rivers were—and oft-times still are—the highways and byways of America. Cutting through dense forests, roaring through deep canyons, and snaking along vast plains, these liquid highways have been avenues of travel since primitive man first conjured up the idea of a craft to float these vast roadways. For thousands of years, people have used these highways for hunting, trade, commerce, travel, adventure, and exploration.

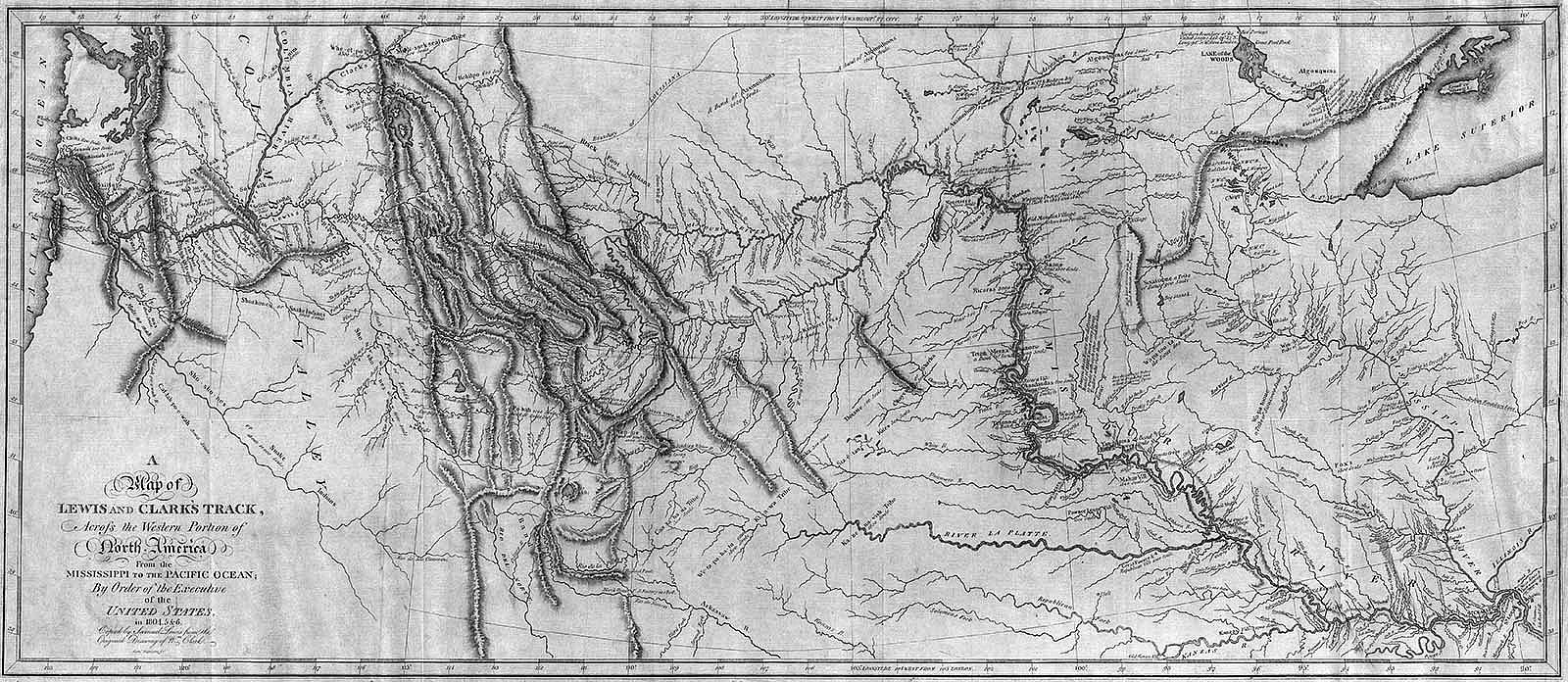

Indeed, one of the primary goals of the 1804 Lewis and Clark Expedition was to find a watercourse that would connect the east and west coasts of North America, binding together the vast country that had just become part of the United States. Traveling through lands foreign to the white man—but well-known to the local population—the expedition failed in its quest to discover a continuous river route to the west coast. It wasn’t for lack of trying, though; the route simply wasn’t there.

They had not anticipated the great backbone of the West as a final impediment to their goals. Nonetheless, rivers such as the Missouri, Yellowstone, and Platte became the most important avenues of travel from St. Louis, Missouri, to Montana and Wyoming prior to the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869.

Thirty-five years later, two adventurous men from Cody, Wyoming, attempted to re-create the experience of river travel in the manner of Lewis and Clark, the fur trappers, French-Canadian engages, and a host of early explorers and adventurers. In 1904, the centennial anniversary of Lewis and Clark’s epic departure from St. Louis up the Missouri River, Gus Holms, age 31, and his father, John, age 60, set out on a 3,000-mile journey down the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers. Their odyssey in a primitive boat of their own making was the adventure of a lifetime.

Early pioneers in the fledgling 8-year-old town of Cody, the two Holms had dreamed of this journey for several years. Their goals included re-creating Lewis and Clark’s voyage down the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers to St. Louis in 1806, and visiting the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, touted to be the largest world’s fair ever and designed to celebrate the hundred-year anniversary of the Louisiana Purchase. Originally scheduled to open during the actual centennial in 1903, delays postponed the premiere until April 30, 1904.

The romance of adventure

Although not specifically mentioned in news articles of the day, the sheer romance and adventure of the undertaking must have been a strong draw for Gus and John Holms. Writers have waxed poetic about the peace, tranquility, and restorative powers of rivers, along with the adventure that excites the soul.

In Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, for example, Huck mused over the serenity of life on the water, “We catched fish and talked, and we took a swim now and then to keep off sleepiness. It was kind of solemn, drifting down the big, still river, laying on our backs looking up at the stars, and we didn’t ever feel like talking loud…” Anyone who has floated a river on a pleasant summer day can surely appreciate that sentiment.

Gus Holms, who had prospected and mined for gold in the Black Hills of South Dakota and later plied that trade in the Nevada goldfields, was at the time proprietor of Gus Holm’s Tonsorial Parlor (barber shop) in Cody. John Holms, a Cody city councilman, was a carpenter and builder by trade, and no doubt built their craft.

Reluctant to sail from Cody down the Shoshone River and risk the treacherous waters of the Big Horn River downstream, Gus and John Holms traveled ninety miles north to the Yellowstone River and Billings, Montana, where they would construct the vessel and commence their journey—the same stretch that Captain Clark and his men traveled on July 25, 1806, during their return trip to St. Louis.

How to build a bateau

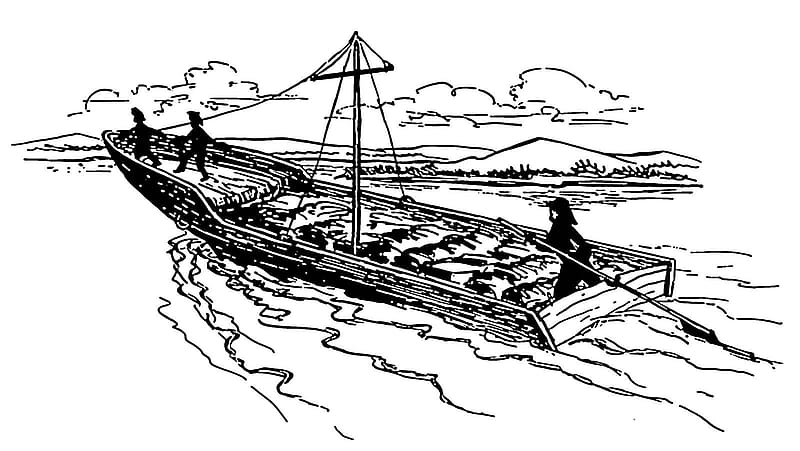

For their journey, the two built a bateau—a shallow-draft, long, flat-bottomed open boat, with the bow and stern somewhat pointed and sometimes tilted upward. They were reliable and generally easy to build without detailed plans. These boats were used extensively in North America, particularly during the colonial days and western fur trade. In several instances, the Lewis and Clark journals describe some of their boats as “bateaux.”

The Holms’s craft was eighteen feet long with an eight-foot beam, two-foot depth of hold, and slightly squared ends. Tent material was stretched over a light wood framework to provide protection from the elements. A couple of stout oars afforded extra propulsion to help them get out of tight places, while a sweep in the stern provided steering. A short flagstaff proudly flew the Stars and Stripes.

A Billings Gazette newspaper reporter provided an onsite description of the vessel. “The craft they turned out has hardly the lines of symmetry of a cup defender,” he wrote, “but she looks staunch and seaworthy and withal is roomy and commodious and suits her builders and designers, probably of the most importance to them, as they alone are to occupy it, being crew, officers, and passengers.”

Launch

The intrepid sailors set off on May 16, 1904, from a point described as near “the old wagon bridge east of the city [Billings].” Coinciding with high water season, the men hoped the spring run-off would help speed them along their way. At the time of sendoff, “There was no crash of music, no jostling of crowds, no stylishly dressed young women with pale face to break the traditional bottle of wine,” according to the Gazette. Instead, drinking a toast with bottles of beer instead of champagne, a few well-wishers that included Sam Salsbury, Billy Vale, and Theodore Fenske were on hand to see their friends off and bid them well.

“Sam Salsbury gave a whoop and helped father and son shove, and the modest—so modest that she has not even been named—boat…bobbed up and down on the turbulent Yellowstone like a bottle emptied of its contents. But for all the simplicity and utter lack of ceremony, the launching of the craft was a success, and the first move had been made in a voyage that had St. Louis Mo. for its terminus.”

Navigating the Great Plains

Traveling northeast through Montana, the adventurers passed many historic locations along the Yellowstone River, including Fort Union at the convergence of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers. There, they sailed onto the Missouri River, where they would spend the rest of their journey until it joined the Mississippi River near St. Louis.

They continued on through the mostly treeless, arid plains of North Dakota and passed Fort Mandan where Lewis and Clark had wintered in 1804–1805. In Bismarck, they made some design changes to their bateau. Apparently anticipating sections of slow water, the men installed a 1.5 horsepower gas engine hooked up to a small paddlewheel at the stern of the boat. Rigged on a hinged frame, the two-man crew could raise the wheel when they encountered sand bars, snags, or low water.

Newly-outfitted and with technology not available to Lewis and Clark, the men continued south where the river took them through the Great Plains of South Dakota. They passed Pierre and the mouth of the Bad River, and then floated to Sioux City, Iowa. At each bend in the river or ridge in the distance, they pondered the frame of mind of Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery.

A thousand miles to go

The Holms were now about a thousand miles from their destination and continued to skillfully maneuver past logjams and “sawyers,” that is, submerged trees that could rip their boat apart. Near Council Bluffs, Iowa, the men intersected the Mormon Trail where it crossed the Missouri and followed the Platte River on its journey to the “Promised Land” in Utah. They traveled south to St. Joseph, Missouri, where the famous, but short-lived Pony Express route originated. A little farther south was Independence, Missouri, the “Queen City of the Trails” and the “jumping off” point for the many celebrated historic trails that opened up the West.

Then, the Missouri River abruptly turned east for the final stretch and eventual meeting with the mighty Mississippi north of St. Louis. With little or no fanfare, John and Gus Holms arrived in St. Louis on August 4, 1904, after eighty days and three thousand miles of river travel. Despite the potential dangers and hardships, they arrived safely with no serious mishaps and in good health. They wired a dispatch to their local newspaper to let the folks back home know they had arrived safe and sound.

St. Louis

It must have been quite a shock for two small-town men just off an extended river voyage to be suddenly thrust among fair crowds that averaged a hundred thousand a day. Nonetheless, the sights were awesome. The Ferris wheel, which debuted in the 1893 Columbia Exposition, reappeared in St. Louis where it could carry more than two thousand people at once. It permitted its passengers a grand view of the vast fairgrounds with visitors wandering through the fairyland of gleaming white palaces surrounded by artistic landscaping.

Most of the states and many countries of the world erected pavilions to proudly show off the agricultural, mineral, technological, and cultural wealth of their homelands. For lighter entertainment, there was the Pike, filled with all manner of amusements, where patrons could ride the exhilarating “Scenic Railway,” predecessor to roller coasters; be awed by a re-creation of the devastating 1900 “Flood of Galveston”; or howl with pleasure in the “Temple of Mirth.” The fair provided entertainment and education for all ages and interests.

Back to Cody

Apparently ready to return home and resume life as contractor and city councilman, John Holms hopped aboard the train and arrived back in Cody the week of August 25, 1904. He deemed the World’s Fair a “marvelous exhibition” and received congratulations from his fellow townsfolk on his successful river voyage.

Gus Holms stayed in St. Louis to take in more of the sights and sounds of the city and the fair. He returned to Cody on September 17 and claimed the river trip was, “extremely pleasant, the only drawback being that it ended too soon.” Regarding the fair, Gus exclaimed that it “greatly exceeded my expectation…and affords one great pleasure and instruction.”

John Holms passed away a mere four years later after a short illness, but Gus developed a life-long passion for transportation, whether by river, horse-drawn coach, or auto. He assisted his brother Aron “Tex” Holms with his Yellowstone Park camping and stagecoach operation and in 1910, Gus established the first auto livery and garage in Cody. He later became a member of the first highway commission in Wyoming and the Wyoming Good Roads movement.

Gus participated in a remarkable five-thousand-mile auto adventure with A.L. Westgard in 1920 traversing the planned, but still primitive, Park-to-Park Highway auto route that would connect the national parks in Wyoming, Montana, Washington, Oregon, California, Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado. Gus Holms died in June 1956.

About the author

Robert V. “Geyser Bob” Goss is a historian of the Greater Yellowstone region and has written numerous articles and books about the area. In April, he headed to the south rim of the Grand Canyon for more “work, play, and exploration.”

Post 326

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.