Nitrate Negatives: Now That’s Explosive Content!

What are nitrate negatives?

Why are nitrate negatives handled with care in archival facilities?

These two basic questions arise when these fragile and very “touchy” items are not on display. Nitrate negatives were first developed in the late 1800s and were used through the 1950s. Eastman Kodak, a well-known photography name, invented these potentially explosive negatives. Yes, explosive negatives are what nitrate negatives can be if not handled properly.

When was the technology launched?

In 1889, the company introduced this negative commercially to the world to replace the large and cumbersome glass plate negatives of the time. It was cutting-edge technology that continued to be used well into the 1900s by professional photographers and videographers. They developed a replacement for professional photographers that made glass plate negatives obsolete.

A Volatile History

Nitrate negatives afforded professionals an easier medium to capture photographs and moving film at the turn of the century. Storage was consolidated. There were fewer accidents that could happen when transporting the negatives since they were essentially shatter-proof with this new technology. Exposure time was sped up. Size consolidation of the actual negative was introduced. There were positives to this advancement in photography technology.

The downside to nitrate negatives?

The negative was known for its combustible qualities. The nitrate was known to burst into flames, spontaneously when stored in large quantities and not properly refrigerated. The first major fire involving nitrate negatives was in May of 1897. At the Bazar de la Charité in Paris, a Lumiere projector burst into flames. The fire resulted in 126 deaths.

In 1914, the Lubin Manufacturing Company’s vault exploded in Philadelphia. Later that same year Thomas Edison’s laboratory in New Jersey burst into flame. The most well-known fire, however; was the Fox film storage fire. A merger between Fox and 20th Century films consolidated the storing of old nitrate film negatives at the 20th Century film studio storage facility.

Until the late 1930s, there was no conclusive evidence as to why these negatives would burst into flame. The epic Fox film fire pushed leading industry officials to question public safety and proper archival techniques used at the time.

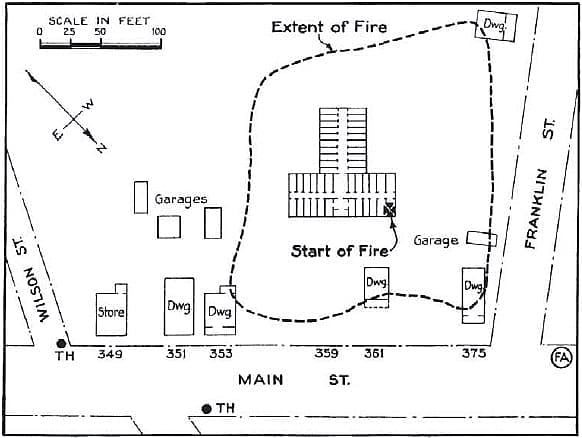

Studies led to understanding three factors that contributed to the perfect nitrate firestorm. The first is heat. Second, the aggressive deterioration of the negatives causes off-gassing. Third, is the friction of multiple negatives stored in close proximity to each other. This trifecta can create its own explosion. Below is a map of the Fox fire area. This fire was devastating to the American film industry. At the time, it consumed more than 75% of the creative content to date owned by the company.

Photo from Wikipedia.

With Loss, Comes Innovation

Soon after the Fox fire, the Society of Motion Picture Engineers reviewed the steps to preserving nitrate negatives. New processes for climate-controlled facilities that would prevent self-combustion were mandated. Subsequently, the invention of the cellulose acetate film took hold. Nitrate negatives were essentially extinct in the last half of the 20th century in the United States.

However, that does not mean that historical societies and institutions like the California Academy of Sciences, the Chicago History Museum, or the Buffalo Bill Center of the West have abandoned preserving history that is on these delicate negatives.

Collection at the Center

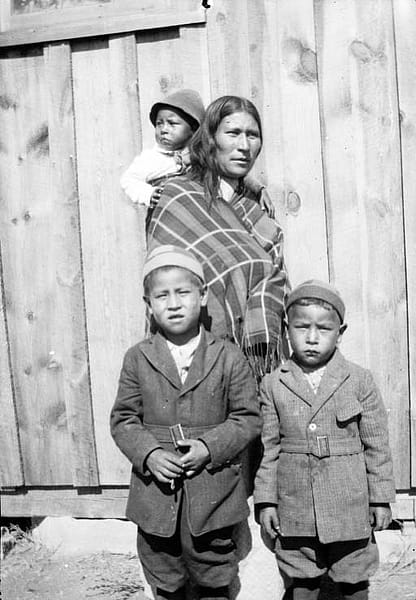

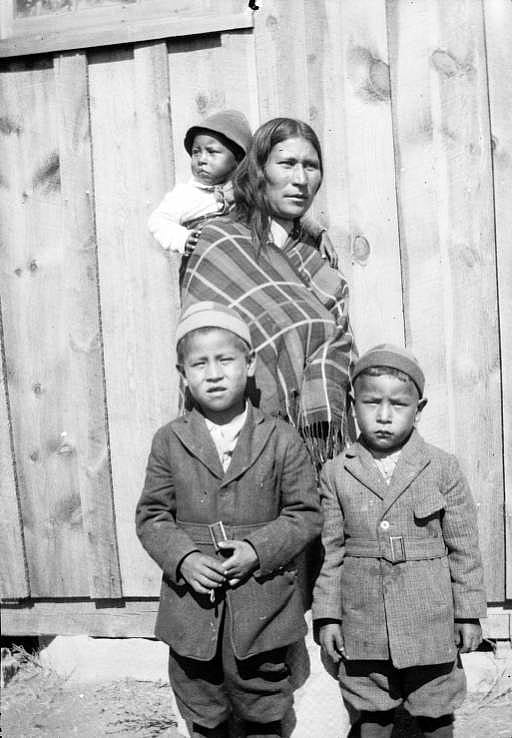

Thomas Marquis was a photographer that lived among the Cheyenne on the western plains in the early 20th century. The Center acquired this special collection in 1999. It consists of 462 nitrate negatives categorized into three sets!

So, how does the Center of the West care for nitrate negatives?

Proper Care for Nitrate Negatives

- An archivist must be sure to evaluate the present condition of the negatives and identify either the evidence of deterioration or labeling if negatives are nitrate negatives.

- Digitization is key to preserving historical information from these negatives.

- Be sure to minimize handling and when you scan to digitize at the highest resolution and save preferably as a TIFF. This becomes the “digital negative” for the original work.

- Use paper sleeves for each negative and labeling should be done with the least destructive means to identify the negative.

- Be sure to seal it in a Ziploc bag or in a moisture barrier-approved container to keep the material dry.

- Store in an archival freezer at least at -20 degrees Celsius.

Written By

Kim Zierlein

To quote one of my favorite movie lines..."Life is just life, Wyatt." This simple, yet profound truth shared between Doc Holiday and Wyatt Earp reverberates throughout my being. There is nothing simple, normal, or wrote about life. We each have a path, and it is unique. Filled with struggles and passions; life is something that is to be lived. How you live your life; however, dictates the legacy that you will leave for so many. I have been led on a journey that through all its turmoil and peace, I hope to leave a lasting legacy that my son, and those I have touched can appreciate. My prayer is that I teach them to commune with the soul inside themselves...no matter how hard those truths are at times. I live on a vast "Frontier" in so many ways. It is not only a place, but rather it is a living fully in your mortality on the way to your infinity. I know confusing right!? But the more you read, and learn about me, and what I wish to share, the more that statement will make sense to you on a personal level. I have a passion for finding the beauty in it all...I am not just trying to experience a perfect moment; I am trying to tell of a life well-lived. I pray each day for brokenness, and for a heart that seeks truth. I want to discover this true Covenant through photography, writing, and creativity.