I Butteri: Italy’s Legendary Cowboys of the Maremma – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2022

I Butteri: Italy’s Legendary Cowboys of the Maremma

By Ruffin Prevost

Photographs by Gabrielle Saveri

On October 8, 2022, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West opens a special exhibition of photographs of cowboys. The images capture hardworking men (and a few women) who are expert equestrians, toiling in a rugged landscape, tending to cattle and horses that are part of a legacy dating back many years.

Their connection to the land is impassioned and inspired. But modern bureaucracy, changes in the beef industry, and waning interest from younger workers are all threatening their cherished way of life. These authentic working cowboys — widely admired, and sometimes even imitated — are becoming increasingly scarce.

If that all sounds familiar, you might be surprised to learn that the cowboys in these photos don’t live and work in the American West. They are I Butteri (pronounced ee boo-teh-ree, meaning the cowboys or the mounted herders), the legendary Italian cattle breeders and horsemen of the Maremma, a rugged coastal region that stretches from the plains of northern Lazio to the beaches and inland areas of the southern Tuscany.

Some of the similarities between the two cowboy cultures were clearly apparent to photographer Gabrielle Saveri. There’s also the historic connection that comes from a legendary meeting in 1890 between William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and a group of Italian cowboys (see Buffalo Bill and La Sfida sidebar, below).

Saveri grew up in California, but lived for years in Rome, working as a journalist there before returning to Northern California, where she now lives and works in the Napa Valley as a photographer, videographer, and writer. Italy’s cowboys share a lot with those in the American West, she said.

“They love their horses and their cows, and they truly love the land,” Saveri said. “I think we should pay homage to these cultures that respect nature and the natural world. Wyoming is like that, and I hope people see and appreciate the connection these people have to their history and their land.”

Saveri’s father’s family was from Italy, and she visited the country frequently as a child before working there as an adult. But her route to photographing the famous butteri of the Maremma was circuitous and unexpected.

“When I was young, I loved horses and loved to ride. I even dreamed of being a jockey. But life kind of took me down different paths,” she said. “Living in Rome as a reporter, I kept hearing about these Italian cowboys, but I didn’t know how to find them. Things were busy, and I left Italy and never realized that goal.”

More than 20 years later, a random conversation in a California restaurant helped connect Saveri to a ranch in Italy.

The next summer, in 2013, Saveri traveled to Alberese, a small, rural, agricultural community where one of the last large-scale cattle ranches of the Maremma endures.

Pedaling at sunrise on an ancient, rusty bike in her riding gear, Saveri joined the local butteri, who took her out to move a herd of young horses. The butteri asked that she not use her full frame camera gear on horseback, citing safety concerns, so Saveri had to use a basic point-and-shoot camera from the saddle.

After a plunge on horseback into the sea as the grand finale of her ride on her first day, Saveri came away with only 10 usable photos after her camera got wet in her saddle bag.

“But we got to gallop all over the hills and olive groves, and it was such a great experience for me,” she said. “It was a dream come true.”

Saveri returned every summer until the COVID-19 pandemic to take more photos of Italian cowboys, all while sharpening her skills as a photographer, which was a relatively new trade for her after writing for Newsweek, People, Business Week, and other outlets.

Her photos “offer an insider’s perspective on the everyday activities of the butteri, which, bathed in golden Tuscan sunlight, somehow seem so much more than mundane,” said Karen Brooks McWhorter, the Center’s Collier-Read Director of Curatorial, Education, and Museum Services.

“Part of what drew me to this was that it was so spectacular visually,” said Saveri, whose photos are full of sumptuous colors, lavish textures, and dappled sunlight.

“The colors and textures of the landscape and the clothes are wonderful,” she said. “And they are out working early in the morning and late in the day, so the light is a beautiful, golden light that’s just perfect.”

The workdays are long and difficult, and the pay is low. Which is part of why ranches are having trouble recruiting new cowboys. A few years back, the Tuscany regional government launched a vocational training program for new cowboys, even accepting for the first time female applicants for the typically male-dominated spots.

Saveri said only about two or three dozen full-time working butteri remain in the region — others put the number even lower — not only because of a series of economic recessions in Italy, but also as a result of changing European Union regulations on the beef industry.

Some small horse and cattle ranches remain, subsidizing operations with agriturismo revenue from hosting guests. But the large-scale ranches that dotted the landscape centuries ago are virtually gone now, with the government working to support and even administer the remaining major operations.

“They’re trying so hard to preserve it, because this is such an old culture,” Saveri said. “The butteri say they were the first cowboys in Europe, dating to the spread of agriculture from Etruscan times,” some 2,500 years ago.

“I just hope they prevail,” she said. “If the butteri disappear, that will be a real tragedy.”

About the author

Ruffin Prevost is a freelance writer from Cody, Wyoming, and editor of Points West magazine. He operates the Yellowstone Gate website and writes for Reuters News Agency.

Sidebar: Buffalo Bill & La Sfida

Cowboys had been working the land in what is now Italy, tending to horses and cattle, for more than 20 centuries before William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody first climbed into a saddle.

But that didn’t stop the legendary showman from issuing a brazen challenge when the Wild West made five stops in Italy in 1890.

“Buffalo Bill had a real habit of making bets with locals when touring, to raise money and generate some press for shows,” said Renée Laegreid, a professor of history at the University of Wyoming who is writing a book about Cody’s encounter with Italian cowboys, drawing on a decade of research in Italy and from the Papers of William F. Cody at the Center of the West.

Laegreid has also consulted archives in Florence and Rome, and interviewed dozens of Italians about “La Sfida,” which translates to: challenge, contest, or competition.

La Sfida is so well-known that it has become a proper noun,” Laegreid said. Many people in Italy know the story of Buffalo Bill and the Italian cowboys.

Cody issued the challenge while “hob-nobbing with some of the royalty around Rome before a show,” Laegreid said. Cody and an Italian nobleman, the Duke of Sermoneta named Onorato Caetani, debated whose cowboys were more skilled.

Caetani provided several wild colts from his estate, and Buffalo Bill bet that his cowboys, along with the Indigenous Peoples riding in his show, could mount and ride the horses, and that the Italians couldn’t.

If Buffalo Bill won, he got to keep the horses. If the Italians succeeded, Buffalo Bill would donate a huge sum to the poor, with accounts ranging from 1,000 to 10,000 Lira. Regardless, “that was a lot of money,” Laegreid said.

The Native riders succeeded, as did Buffalo Bill’s horsemen, although the Italians complained that the Americans were too rough, “and basically thought they were barbaric in how they did it,” Laegreid said.

The Italians were doing well when their turn came, Laegreid said, but Buffalo Bill stopped the contest just as it was concluding, claiming the butteri had taken too long.

Buffalo Bill didn’t pay, nor did he keep the horses. American and Italian newspapers erupted in a firestorm of controversy “with everyone hurling insults, and it was really quite amusing, and it remained ‘unresolved,’” at least from the American perspective, Laegreid said.

But most Italians figured they had won, and had no choice but to become gracious winners. “The cowboys themselves absolutely believe they won, and it has become a point of pride in the region,” she said, with Italians today still recalling stories of family connections to La Sfida.

“The unresolved aspect of La Sfida remains fascinating, not so much because Buffalo Bill may have tried to weasel out of paying a debt,” Laegreid said. “But because it is about how both cultures viewed their cowboys and traditions. It was less a contest between men and horses, and more a contest of traditions between the new world and the old.”

Post 333

Images:

Buttero, a 2016 photograph of an Italian cowboy, is part of “Italy’s Legendary Cowboys of the Maremma,” a special exhibition by photographer Gabrielle Saveri, on view October 8, 2022 – August 6 2023 in the John Bunker Sands Photography Gallery. All photographs ©Gabrielle Saveri. All Rights Reserved.

Riding Boots and Two Hooves, 2016. Photograph ©Gabrielle Saveri.

Butteri Herding Maremmano Horses at Sunset, Spergolaia, 2015. Photograph ©Gabrielle Saveri.

Portrait of Two Riders, Pitigliano, 2016. Photograph ©Gabrielle Saveri.

Portrait of Buttera Margherita Barco, Alberese, 2017. Photograph ©Gabrielle Saveri.

Performance at the 1st National Raduno (Butteri Rally), Spergolaia, 2015. Photograph ©Gabrielle Saveri.

A Buttero Demonstrates Roping Skills, Rispescia, 2017. Photograph ©Gabrielle Saveri.

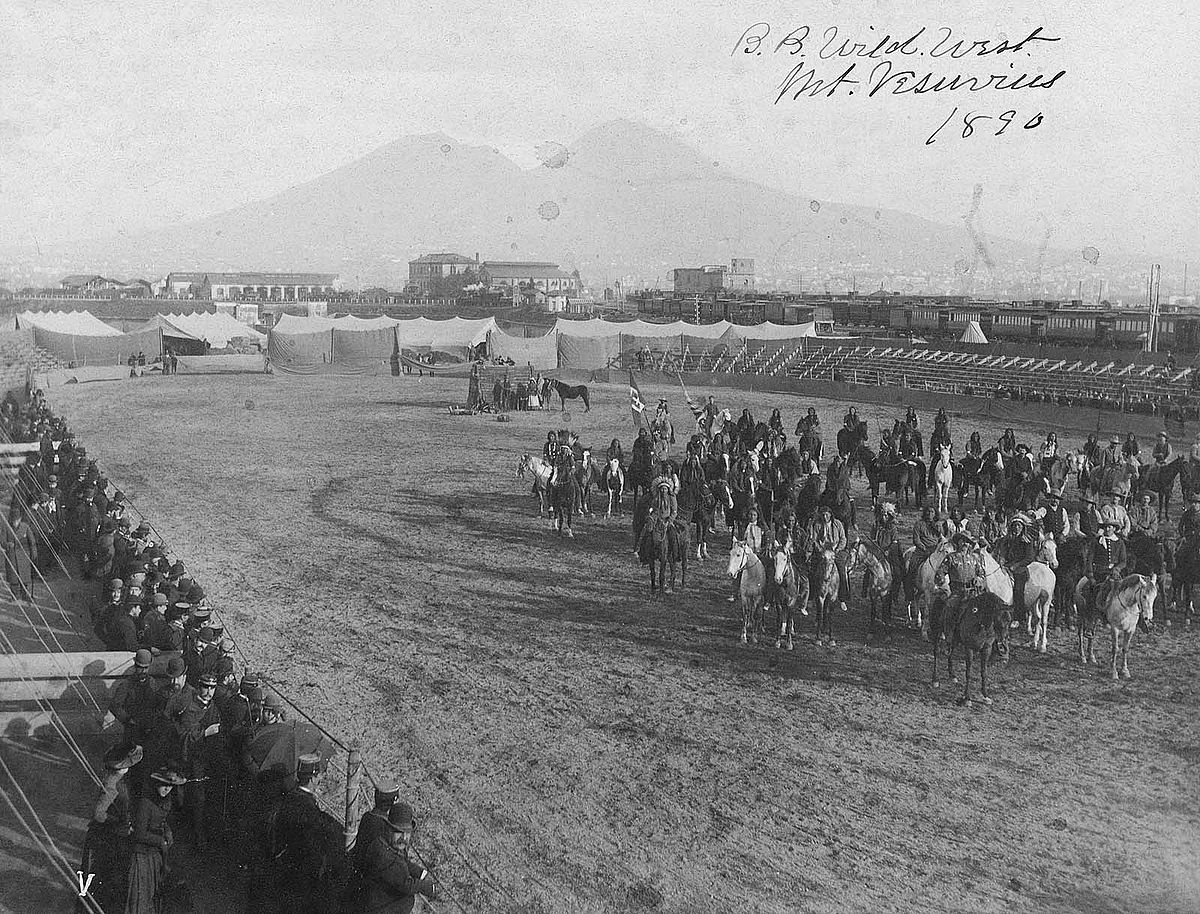

William F. Cody at the front of a group of cowboys and Native American men mounted on horses in Wild West show arena, 1890. Mount Vesuvius, Italy, appears in the background. MS 6 William F. Cody Collection, McCracken Research Library. P.69.0806

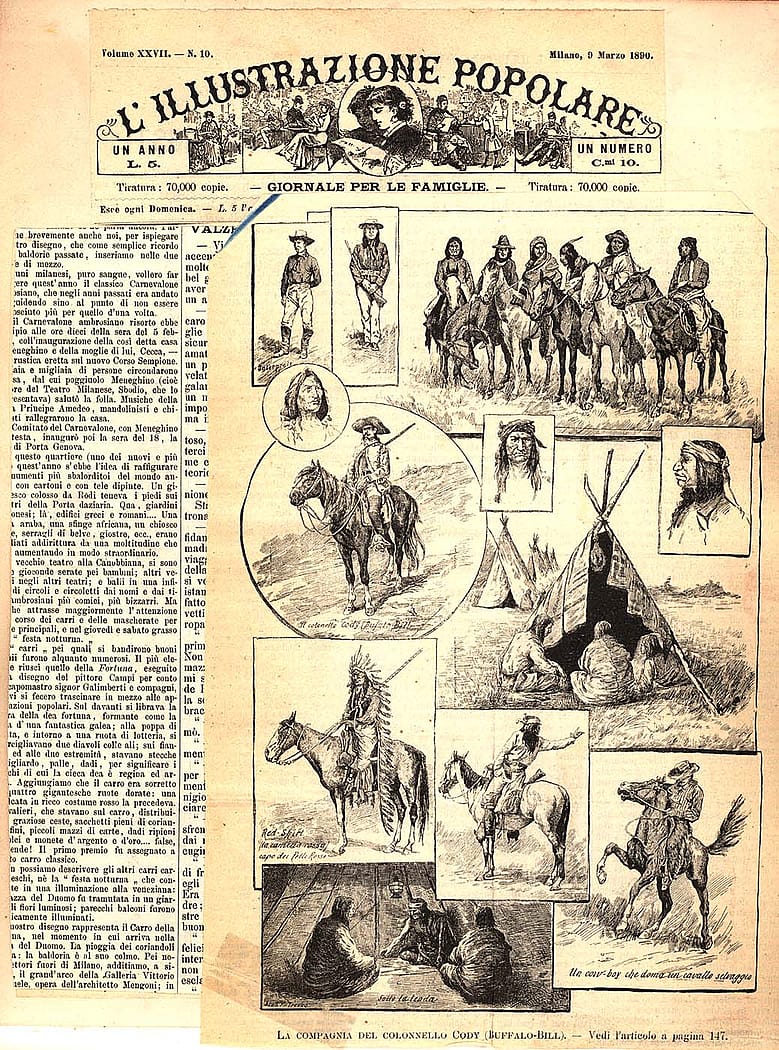

A Buffalo Bill’s Wild West scrapbook containing newspaper clippings and illustrations of the show in Rome, Italy, 1890. MS 6 William F. Cody Collection, McCracken Research Library. MS6.3777.094b

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.