Buntline and Burke – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2022

Buntline and Burke: Buffalo Bill’s Peerless Promoters

By Ruffin Prevost

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody was an authentic and skilled frontier scout who accomplished an amazing range of impressive achievements that would contribute to his widespread fame and public acclaim. But without the efforts of two men, it’s unlikely he would have become the household name he remains, even more than a century after his death.

One of those men went by the name Major John M. “Arizona John” Burke, even though he never held such a rank, and had no special connection to Arizona. The other was a celebrity writer called Ned Buntline, which wasn’t his actual name, but a pseudonym drawn from nautical jargon.

Together, Buntline and Burke helped turn Buffalo Bill into one of the most famous people in the world, and in the process shaped enduring ideas, perceptions, and mythologies about the American West, while also ushering in modern methods of publicity and promotion that remain in widespread use today.

While most remember Buffalo Bill mainly for his Wild West production—which Burke tirelessly and skillfully promoted—that show probably wouldn’t have existed if Buntline hadn’t first elevated Cody’s profile in print and on stage.

“I absolutely think that he developed the popular culture of the American West,” author Julia Bricklin said of Buntline, who was born Edward Zane Carroll Judson in 1821 in Stamford, New York.

Buntline became a famous author and publisher of adventure tales, and was himself an irrepressible rogue whose amazing exploits Bricklin documented in her book, The Notorious Life of Ned Buntline: A Tale of Murder, Betrayal, and the Creation of Buffalo Bill.

“Going backwards, the whole reason people were so excited about Cody was because of Buntline’s previous works, and his recognition as an authority figure of that exotic West,” said Bricklin, who relied on the McCracken Research Library in part for source materials about Buntline.

Buntline (a term used for a rope attached to the bottom of a square sail) served in the U.S. Navy, and later spent time in Florida during the Seminole Wars. He drew on those experiences to create a series of thrilling stories published in newspapers, dime novels, and various publications he started himself and with partners.

Despite being a heavy drinker and a prodigious philanderer, he was an amazingly productive, famous, and lucrative literary force, albeit never taken as seriously as was his longtime ambition.

Bricklin said she was drawn in by the details of Buntline’s personal life while researching him, and was “amazed by how crazy this guy was, keeping mistresses in four different towns at the same time, but still being able to write the kind of output he did while juggling a very ambitious program of alcohol” and other ventures.

Buntline was “an exceptional listener and he had an exceptional memory,” she said. “And I think his time with Buffalo Bill was at the peak of his cerebral faculties, and he was probably as sober as he was ever going to be then.”

In fact, Buntline met Cody in Nebraska in 1869 while returning home from a temperance speaking tour in California.

Both men probably saw their meeting as mutually beneficial, with Buntline looking for stories from a rising military standout, and Cody seeking to boost his profile and that of his colleagues’ efforts in the West.

Buntline spent time traveling with Cody, including to engagements on the East Coast aimed at sharing news of the military’s exploits with influential players there.

Buntline wrote about Cody’s adventures in a handful of popular dime novels, and eventually convinced him to star (reluctantly) in Scouts of the Prairie, a stage production written and conceived by Buntline that featured Cody and fellow cowboy and scout Texas Jack Omohundro playing themselves. What the show lacked in critical acclaim, it made up for with box office success.

Neither Buntline nor Cody could have imagined their production would play to sold-out houses up and down the East Coast, Bricklin said.

But ever one to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, Buntline eventually “blew it like always,” Bricklin said, “because he just could not manage his alcohol or his greed.”

Cody and Buntline had a falling out in late 1872 but remained friendly as Cody’s star continued to shine brighter, and Buntline’s slowly faded.

Fortunately for Cody, Burke was then managing the career of dancer and actress Giuseppina Morlacchi, who co-starred in Scouts of the Prairie alongside Cody and Omohundro, whom she married in 1873.

Like Buntline, Burke had met Cody in 1869, and was immediately impressed by the dashing young hunter and scout, said Joe Dobrow, author of Pioneers of Promotion: How Press Agents for Buffalo Bill, P. T. Barnum, and the World’s Columbian Exposition Created Modern Marketing.

While working to promote Morlacchi and her stage production with Cody, “Burke continued repeating and enhancing stories of Cody’s legendary career, and not long after that, Cody decides to abandon the stage for the arena,” Dobrow said.

Burke became general manager and the first employee of the Wild West Company. He employed all the tricks he knew, along with many new ones, to create a frenzy of interest before the Wild West arrived at its host cities.

Burke pioneered the idea of celebrity endorsements, which were not then widely used. After Mark Twain saw the Wild West twice in one week in Elmira, New York, in 1884, Burke used a seemingly spontaneous thank-you letter from the famous author to publicize the show in hundreds of promotions, Dobrow said.

Burke also appears to have invented a precursor to what is now the press kit, Dobrow said, a revelation that dawned on him while researching the promoter in the McCracken.

“They had a little published packet that had all these stories about Buffalo Bill and his battles and so forth,” he said. “As I looked at it, I saw the pages were perforated.”

Dobrow said he came to realize that Burke, working on advance publicity for the Wild West, would roll into a city where the show was opening, and guarantee editors an exclusive story about Cody, tearing out one of the anecdotes from his perforated press kit.

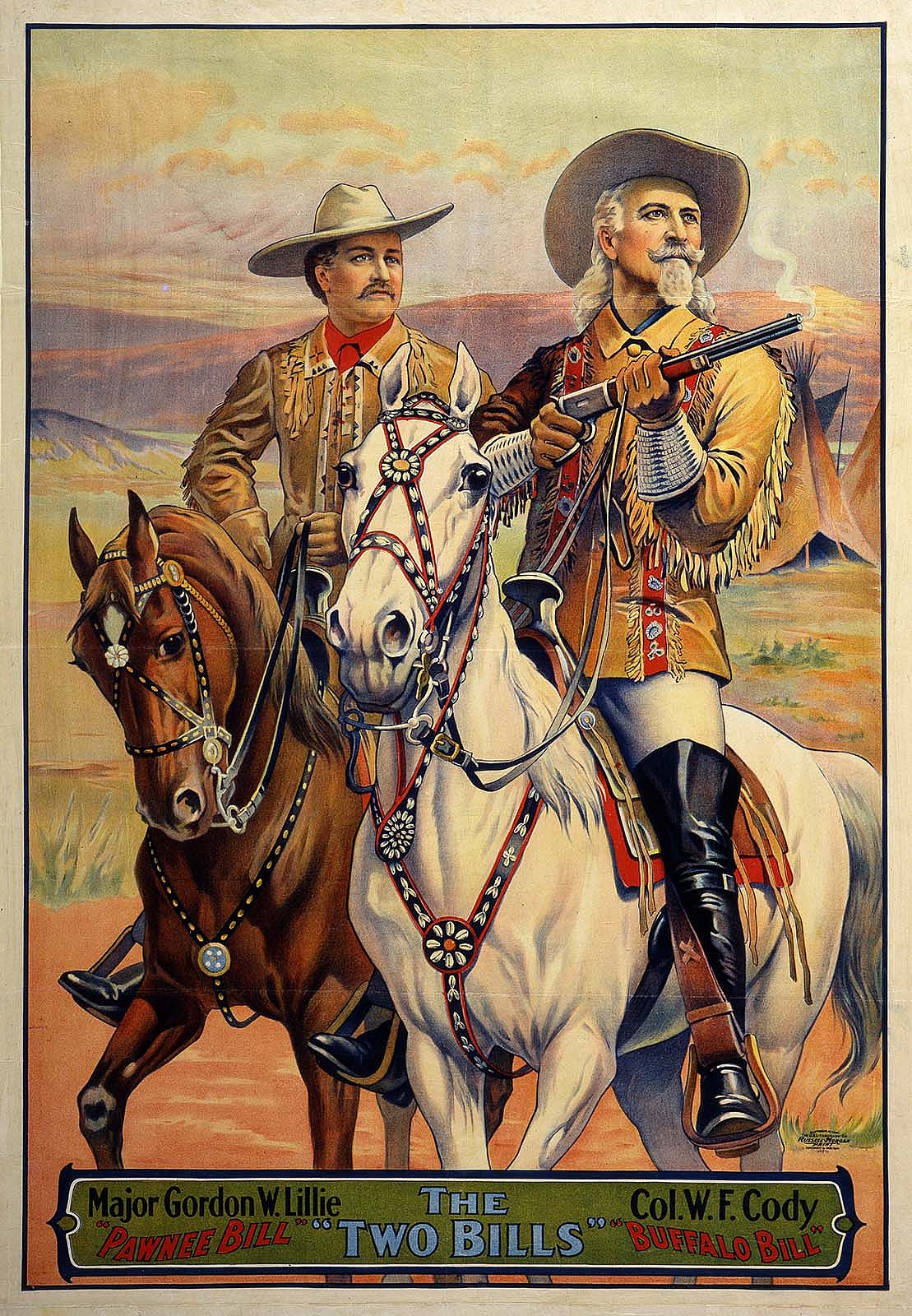

Burke used the latest printing technology to churn out 7,000 posters or more for each show, “covering every vertical surface” in cities around a performance venue. He offered free show tickets in lieu of payment for laborers posting handbills, often using an iconic image of Cody’s face against a bison with only the words: “I am Coming.”

Burke used the same poster in France, where he showed up weeks in advance to promote the show, having learned French before the trip.

In Germany, he put giant posters on horse-drawn wagons, creating what we now know as the mobile billboard, Dobrow said. “The Germans were not sure what to make of it all, because they had never seen such brash advertising techniques before.”

Burke regularly scanned newspapers for negative or critical coverage of Cody or the Wild West, and would mount aggressive responses, an early example of the kind of “reputation management” practiced by modern public relations firms.

He staged endless publicity stunts, roasting an ox on a spit before a press breakfast, or giving reporters a ride through downtown on the Cheyenne-to-Deadwood stagecoach, which was a central part of the show.

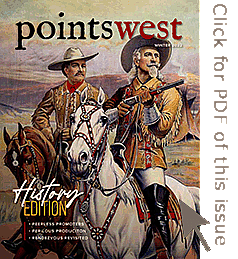

Product licensing was another innovative effort by Burke, with Parker Brothers launching a Wild West board game in 1898, and Buffalo Bill’s image appearing on everything from buttons to cigars to trading cards.

“All of this was an extremely complex enterprise—hundreds of employees and animals—and would be a challenge to manage even today,” Dobrow said. “It’s really remarkable given the limited resources and technology he had that Burke’s efforts were so sophisticated.”

Burke’s pioneering methods paid dividends for nearly 40 years, until he and Cody both died in 1917. His efforts succeeded in large part because, like Cody and Buntline, he was a larger-than-life persona, Dobrow said. But also because he was an excellent storyteller, and well-connected through personal relationships to the reporters and editors who covered the Wild West.

But just as important, Burke had a vision of how the exploitation of, and later, the closing of the frontier were compelling stories that captured imaginations around the world.

“I really believe that Burke understood the growing fixation and mythologizing of the American West,” Dobrow said. “He understood that Cody was sort of a symbol of the dying West and the new West, all at once.”

Bricklin sees Buntline as someone who was also enchanted by the West, and wanted to share its stories with the wider world, despite his often cynically opportunistic approach to storytelling.

“I think Buntline was making a sincere effort to record and share these amazing stories of a vanishing West,” she said.

“Throughout the history of the American West, many western characters, like William F. Cody, led tough lives and survived several heroic escapades,” said Jeremy Johnston, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Ernest J. Goppert Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum. “Yet Buffalo Bill’s professional connections to characters like Ned Buntline and John Burke transformed his real exploits and various careers into sensational dramatic narratives that made him an international sensation,” Johnston said.

“After people finished reading Buntline’s dime novels and viewed all of Burke’s stunning marketing material, it became nearly impossible to separate myth from reality regarding Buffalo Bill’s legacy,” Johnston said. “Today’s historians and biographers continue studying the multiple threads that weave this tapestry of myths and facts together, hoping to determine the most accurate historical truth. Thanks to the legacy of Buntline, Burke, and Buffalo Bill, separating the real west vs. the wild west will be an ongoing study.”

About the author

Ruffin Prevost is a freelance writer from Cody, Wyoming, and editor of Points West. He operates the Yellowstone Gate website and writes for Reuters News Agency.

Post 344

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.