A Rendezvous Revisited – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2022

A Rendezvous Revisited: Special Exhibition explores Alfred Jacob Miller’s art like never before

By Tessa Baker

Traveling deep into the Rocky Mountains, trappers, traders, and tribes transformed quiet valleys into bustling extravaganzas of exchange and revelry in the summers of the 1820s and 1830s. Featuring fur trading, tale telling, and merriment, the annual rendezvous attracted thousands from across the West.

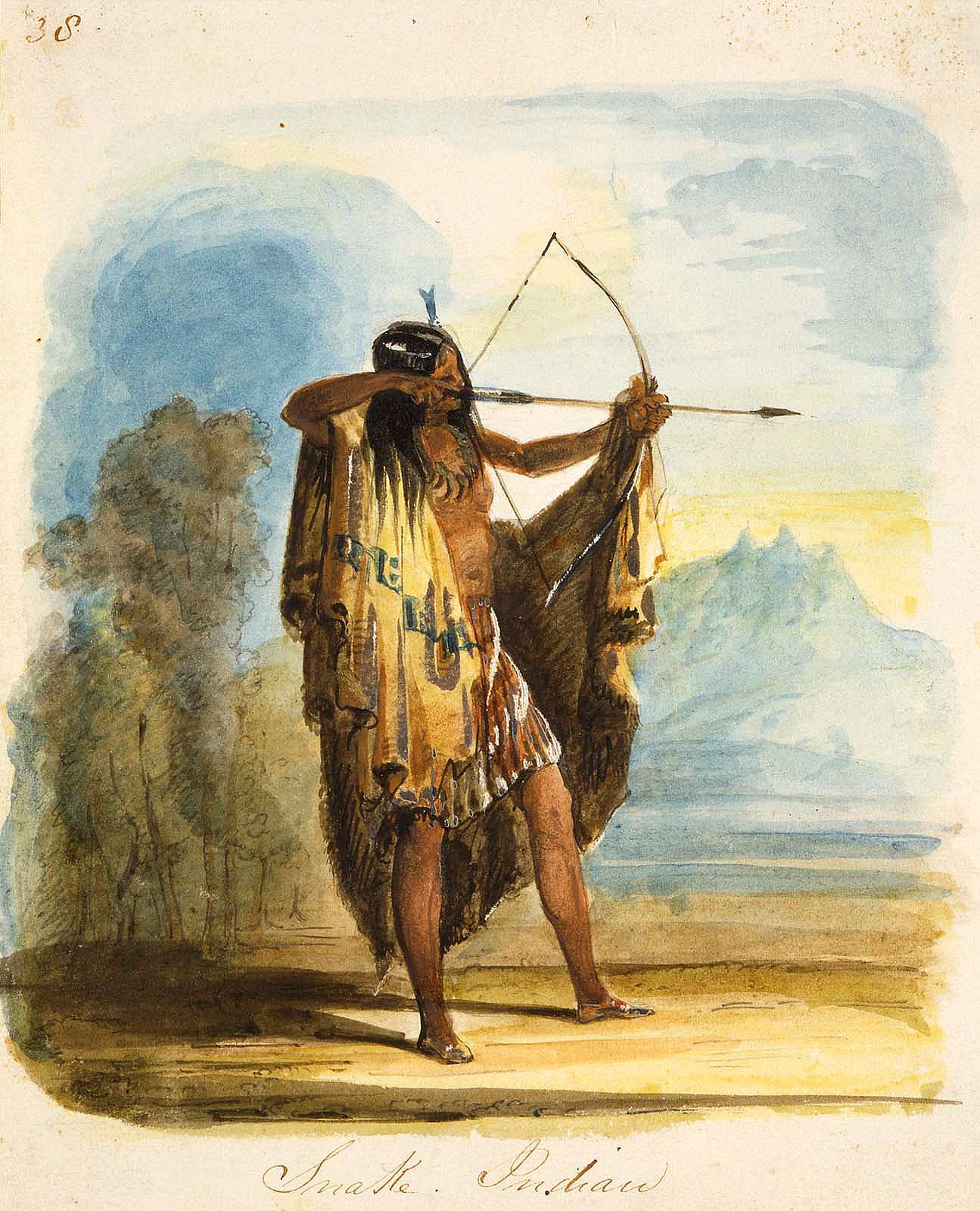

But only one eyewitness captured the legendary scenes on canvas. During an expedition in 1837, Alfred Jacob Miller became the first and only Euro-American artist to attend a Rocky Mountain rendezvous and provide a visual perspective on the rare gathering of mountain men and Indigenous Peoples.

“Miller’s depictions show us this really brief moment in western American history where trade and intercultural relationships were actually really quite amicable and equal,” said Karen Brooks McWhorter, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Collier-Read Director of Curatorial, Education, and Museum Services. “That quickly changed shortly thereafter.”

The amicable and equal relationships varied between fur trade companies and Plains Indian nations. For example, the Blackfoot hated and fought the American fur companies. Yet the Blackfoot traded with the British fur companies. The Shoshone sided with the American fur companies in hopes of acquiring firearms to defend themselves against the Blackfoot, who received guns from the British. In many ways, the American fur trade was a violent trade war. Not to mention the spread of disease among indigenous people and their increased dependency on trade with American businesses.

The rendezvous started in 1825 and ended by 1840. The one attended by Miller took place along a tributary of the Green River in what is now Wyoming.

“It’s a brief period in the American West, but it’s one worth appreciating through Miller’s eyes,” McWhorter said.

A special exhibition opening at the Center of the West on May 20, 2023, will give viewers the opportunity to see Miller’s work as never before.

Featuring nearly five dozen works of art, the exhibition in the Anne & Charles Duncan Special Exhibition Gallery will focus on the connection between Miller and Sir William Drummond Stewart—the Scottish nobleman who hired Miller as the artist for his 1837 expedition. Miller later traveled to Stewart’s Murthly Castle in Scotland, completing many paintings there during the 1840s.

From intimately scaled watercolors to 10-foot-wide canvases, every piece in the Center’s special exhibition relates to Miller’s relationship with Stewart and the artist’s time abroad.

“Never before has a critical mass of Miller’s work depicted for his Scottish patron been brought together,” McWhorter said.

A wealthy adventurer, Stewart played a crucial role in Miller’s artwork. Not only did he fund the expedition that would change the course of the young artist’s career, Stewart also influenced how Miller depicted the western scenes.

“I think that Stewart was very explicit in terms of the kinds of things he wanted Miller to paint,” said Jim Hardee, editor of the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade Journal. “So we see a lot of hunting images, we see a lot of that frontier life interaction with Native Americans.”

Miller’s paintings served as a highlight reel—something of a “what I did this summer” scrapbook for Stewart to show off in Scotland, Hardee said. It’s no accident that Stewart makes frequent appearances in the paintings on a white horse, often in the center, he added.

The Scottish aristocrat is like the “Where’s Waldo?” in Miller’s artwork, McWhorter joked, explaining that the artist painted his patron into many scenes, especially those he commissioned. “Stewart did play a very active role in deciding what ultimately would grace the walls of his castle,” she said.

Stewart’s influence—paired with Miller’s artistic training in Paris and Rome—led to romanticized portrayals of the West, mountain men, and others who roamed the Rocky Mountains.

Mountain Man Myth

Historians of the fur trade widely reference and rely on Miller’s work, McWhorter said, as the artist provided visual interpretations of western clothing, equipment, and everyday experiences in the 1830s.

“He does two paintings—one is sort of a study for the other—of trappers actually trapping, and they’re the only historical images we have of these guys plying their trade,” Hardee said.

Though likely posed, the pieces provide a rare glimpse of trappers doing what they went West to do.

“Bravo for either Stewart or Miller coming up with the idea of, ‘Let’s get some guys to pose so we can record this,’” Hardee said.

The expedition’s mundane moments were not generally the focus of Miller’s artwork made for Stewart’s Scottish estate.

“When you are thinking about a painting for your wall and celebrating your adventure, you’re probably not going to pick a depiction of mucking out the camp or cleaning up breakfast or something like that,” McWhorter said. “It’s going to be the cavalcade—this parade scene—amid a beautiful landscape. There’s a lot of romanticization in the paintings created for Stewart; we need to think about the patron and Miller’s own inclinations.”

Literal romanticization can be seen in Stewart himself, as he had a blond buckskin suit tailor-made in London to wear on his western adventures.

“He had this suit made just to fit into his imagination of what mountain man life was like,” McWhorter said.

Stewart and Miller both contributed to the mythical image of the mountain man “that is still very powerful today,” said Jeremy Johnston, the Center’s Ernest J. Goppert Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum.

“Common laborers like mountain men and cowboys get elevated to this American heroic status that we don’t see with, say, coal miners and oilfield workers,” Johnston said. “It’s people like Alfred Jacob Miller and Sir William Drummond Stewart who make those significant contributions to those mythical depictions—those romanticized views of opening the West.”

In reality, mountain men were just trying to make a living. The fur trade was a large capitalist venture, with natural resources leaving the region to fulfill global demand, Johnston said. As trappers slogged away in the rugged terrain and bitter cold, investors in places like New York profited off their hard labor.

While a few mountain men like Jim Bridger tried to profit from their discoveries out West, “many of them didn’t make a fortune; many of them left the fur trade and went back to farming,” Johnston said. Some trappers shifted from the initial economic motivation to a lifestyle motivation, Hardee said.

“And that’s where that ‘bigger than life’ kind of thing comes in,” he said. “When we think of how Hollywood has portrayed mountain men, I think Hollywood probably has done more damage to what the fur trade was really like than Alfred Jacob Miller ever did.”

‘A Lot to Learn’

From sketches to watercolors to oil paintings, Miller was “incredibly prolific,” McWhorter said. He started as a portrait painter and created some scenes of his hometown of Baltimore and New Orleans, where he was living in 1837 when Stewart invited him on the adventure of a lifetime.

While Miller never returned to the Rocky Mountains, he continued to paint scenes from the West until his death in 1874. His artwork continues to be appreciated in the region that captivated him, and beyond.

“When you look at a collection like this, there’s such a rich tapestry that when you start pulling on the threads, it just goes everywhere—so many connections, so many different interpretations that came out of that,” Johnston said. “From a historian’s perspective, it’s a great example of how one collection can really shape a lot of our interpretations of the past.”

Miller’s written notes about his images also provide important details.

“That gives us little bits and pieces of insight, cultural relations, material culture even—things that we might not have thought about if we didn’t read the notes and descriptions that he kept,” Hardee said.

As people view the Center’s special exhibition, McWhorter hopes they gain insight into what Wyoming was like in 1837, and come away with a better appreciation for the appeal of the West in Europe at that time.

A complementary exhibition also opening in May 2023 will feature artwork by Tony Foster—a British artist whose depictions of the Green River watershed celebrate its cultural, historical, and ecological importance.

“We’ll have this exhibition of largescale, contemporary watercolors looking at the Green, and then Miller’s story takes us all the way back to 1837 in the same area,” McWhorter said.

She also hopes people leave with a better understanding of the complexity of character of Stewart, Miller, and the subjects of his art.

The Center is partnering with the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis to bring in another scholarly perspective on sexuality and gender as it relates to the story, McWhorter said.

“What we have to go on is context, the writings of Stewart and Miller, and also the paintings — looking at these anew, we hope to provide more insight into what we know to be really deep and close relationships among particular men in Stewart’s company,” she said.

Another major theme of the special exhibition is Miller’s depiction of Indigenous Peoples. He invoked stereotypes as a man of his time, McWhorter said, and these stereotypes are worthy of critical evaluation.

“But what kind of merit might those paintings have? What credible or useful information might they actually provide as it relates to Indigenous cultural heritage?” she asked. A particular focus will be on depictions of clothing and accoutrement worn by Native Peoples in Miller’s works, and these historical items’ connections to contemporary design and living traditions.

“There’s a lot to learn from Miller’s paintings,” McWhorter said, “but also, we need to appreciate him as a particular man working for a particular patron at a particular time. Understanding the context is key, and we hope to bring that history to life for our visitors.”

About the author

Tessa Baker is a freelance journalist and former editor of the Powell Tribune. She enjoys everyday adventures with her husband and two boys.

Post 347

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.