Range Wars

While Basque herders shaped the sheep industry through sweat and self-reliance, the rapid growth of sheep ranching more broadly brought it into direct conflict with long-established cattle ranchers. The vast American frontier stretched endlessly, and vast tracts of land remained unsettled; despite this, tensions flared between sheep herders and cattle ranchers, especially in Wyoming where sheep herders drove their flocks to graze. Sam Hanna, Assistant Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum notes, “William F. ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody expressed as much in a 1903 letter to the Commissioner of the General Land Office and former Wyoming Governor, William A. Richards, when he implored him to do something about sheep grazing in the Cody region. He wrote that the animals would ‘devastate the country’ and that as few as two bands could ‘make the North and South Forks above Cody a barren desert.’”

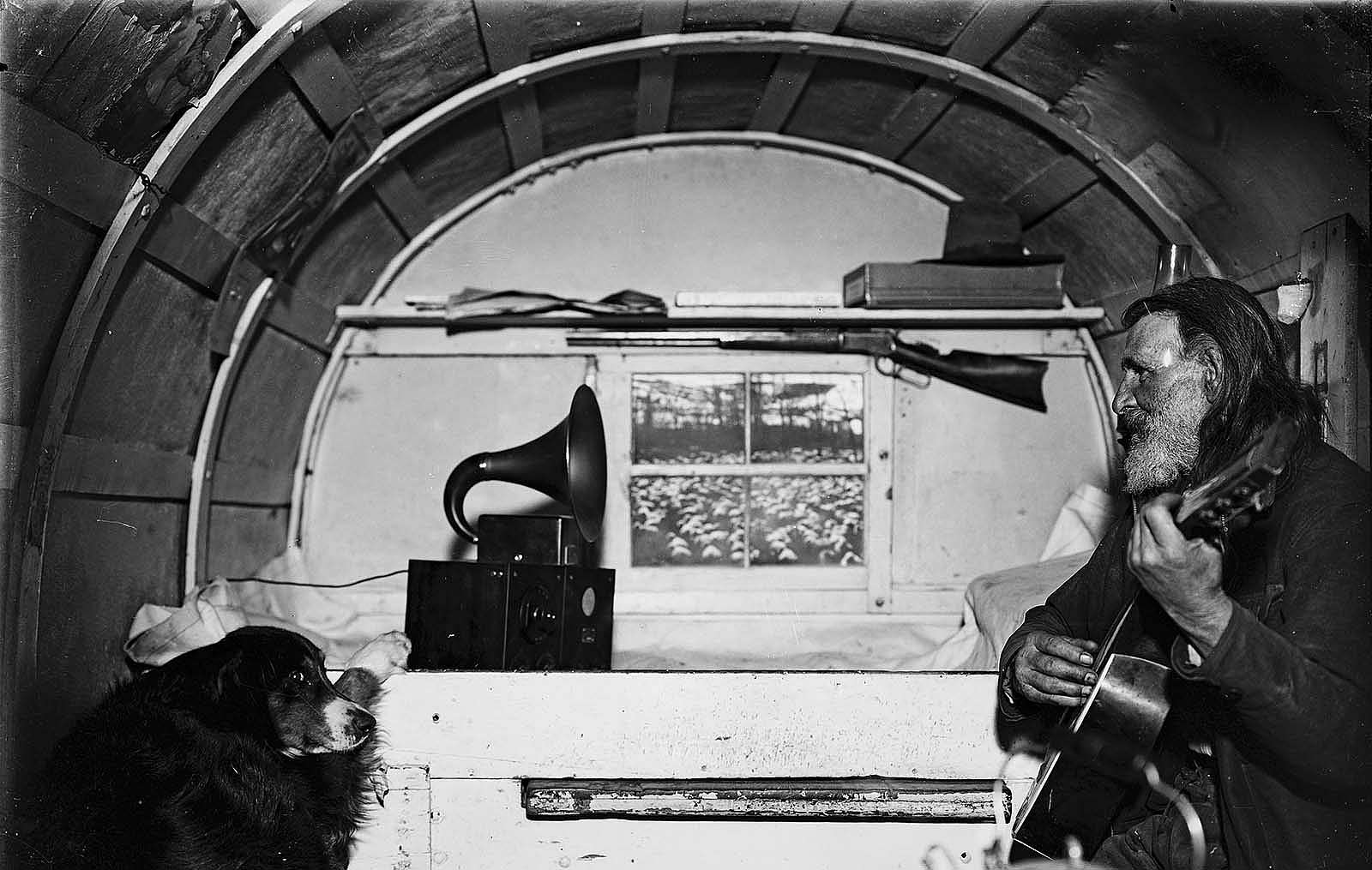

The disputes centered on access to grazing areas on public land. Inveterate cattle ranchers, who had dominated the open range for decades, considered the land theirs by right of legacy and tradition. Then came the sheep herders, whom cattle ranchers accused of overgrazing, polluting water sources, and tearing up the land with the sharp hooves of the sheep. These tensions ignited a series of grazing wars across the West that often turned violent, crumbling the romantic ideal of the “peaceful” open range. One of the most dramatic and deadly episodes occurred during the Spring Creek Raid of 1909, when seven cattlemen attacked a sheep camp near Ten Sleep, Wyoming. They killed three herders and destroyed wagons and livestock. In a landmark trial, five attackers were convicted—the first successful prosecution of sheep raiders in Wyoming. Historian John W. Davis of Worland explains, “The convictions from the Spring Creek Raid put a stop to the mayhem committed in Wyoming against sheepmen. After 1909, there were only two minor raids in the entire state, and no one was injured in either.”

From Necessity to Nostalgia

The violence of the sheep wars eventually diminished, but the industry’s greatest transformation came through progress. After World War II, new technology and economic change reshaped sheep ranching. Four-wheel-drive trucks replaced horses and wagons, and improved fencing reduced the need for long-term herding on the open range. By the 1960s, the sheep wagon had become a relic of bygone years.

Rolling into the 21st Century

Although the era of sheep wagons has long since passed, a new niche industry has emerged: the restoration and repurposing of these historic wagons into functional recreational retreats. Many are now outfitted with premium interiors and all the bells and whistles of a modern camper. Today’s city-slickers flock to the West in search of an “open range” experience, and the glamped-out sheep wagon delivers just that. One such example, the K3 Guest Ranch in Cody, offers a fully renovated 1897 sheep wagon from Worland, WY as a unique lodging option. Owner Jerry Kincaid reports that “the interior of the wagon maintains the original design of the 19th-century sheepherder wagon, but with some improvements for guests, such as a comfortable bed, air conditioning, heat, and running water.”