Byways, boats, and buildings: Yellowstone Lake in history, part 1 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2007

Byways, boats, and buildings: Yellowstone Lake in history, part 1

By Lee Whittlesey

Editor’s note: In the first half of 2007, Lee Whittlesey, Yellowstone National Park Historian, began a study of the history of the Lake Area of the park—particularly those facilities in place at various times throughout history along the north shore of Yellowstone Lake. The National Park Service plans to renovate the existing Lake Village and is working in cooperation with the Montana State University (MSU) Department of Architecture toward that end.

One of the first steps in the process is to develop a comprehensive history of the area to “provide background for how the present facilities and roadways there came to be,” according to the author. “The present study…seeks to reconstruct the cultural landscape features of the Lake Village area 1870 – 2007, to depict some early perceptions of Yellowstone Lake itself, and to assess the role that Yellowstone Lake played in the evolution of tourism in Yellowstone National Park.” In this, the first of four parts, Whittlesey writes about the early accounts of those who saw the lake for the first time.

Second fiddle to a geyser

Yellowstone Lake and the Lake Village that grew up on its shores 1870–2007 are together a region of Yellowstone National Park that was, until 1891, a secondary spot in the park for tourism and visitation. This is surprising when one considers that Yellowstone Lake is a world-class natural feature that, were it located anywhere else, would probably have become a national park on its own.

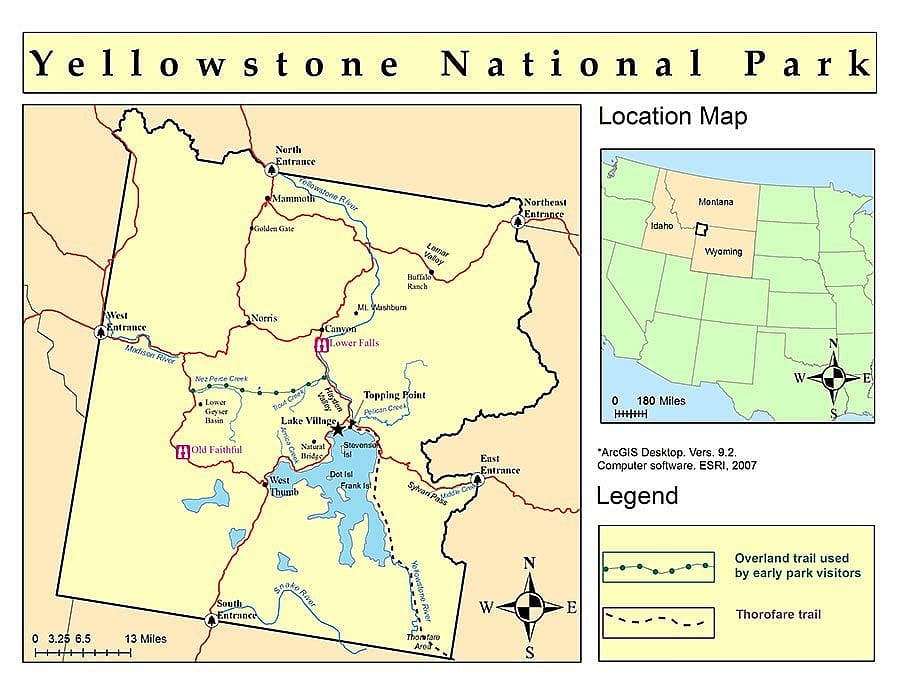

The fact that it remained secondary until 1891 is a testimonial to the lake’s location—remote until a road was completed to it from Old Faithful—and also to the fact that other places in Yellowstone Park contain the so-called “greater” wonders of the geysers at Old Faithful to the west and the canyon and large waterfalls to the north.

In her as yet unpublished master’s thesis, “Pleasure Ground for the Future: The Evolving Cultural Landscape of Yellowstone Lake, Yellowstone National Park 1870–1966,” geographer Yolanda Lucille Youngs describes the lake with details from her own research and a variety of other sources:

“The lake is 20 miles long, 14 miles wide, and expands across a total of 136 square miles. It is also a cold lake that freezes over entirely during the winter and has an average temperature of 41 degrees F. With 110 miles of shoreline, Yellowstone Lake has more than 75 miles of that shoreline beyond the reach of any major road… Its high winds, cold lake temperatures, heavy winter snowfall, and freeze-over are all part of the lake’s mountain climate. Large waves often develop during frequent summer wind storms and contribute to erosion along the lakeshore.”

Early visitors to Yellowstone Lake

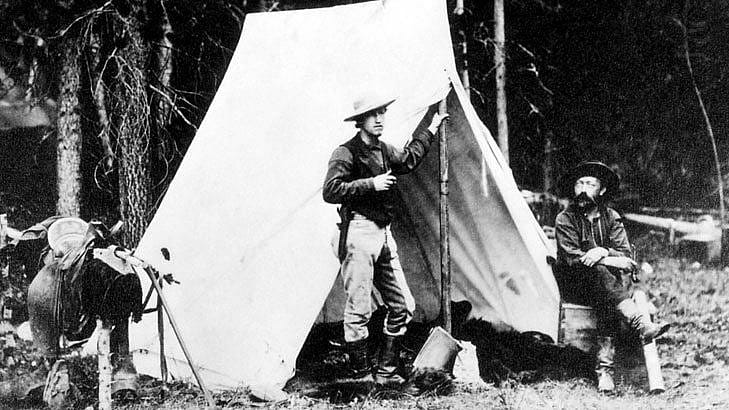

There is some evidence that Indians frequented the shores of the lake long before the establishment of the area as a national park in 1872, and fur trappers visited the Yellowstone country every year from 1823 to 1840 with a variety of tales about the park’s natural features. Some early accounts were verified with late-in-life memoirs as individuals traveled West, but didn’t record their memories until decades later.

Prospector A. Bart Henderson, who reached the area in 1867, had a crude map that led him and his party to the lake. This tells us that the lake was then “famous,” at least to Henderson. It means that oral stories about the lake had gone with travelers to some parts of the West and had found their way into the consciousness of at least some persons by that time, even after the 20-plus years (1841 – 1862) of little or no documented visitation to the upper Yellowstone country by whites.

Jim Bridger, probably the most famous of all fur trappers, visited Yellowstone Lake in 1836, 1846, and again in 1849. He visited at least eight times with a variety of cohorts, entering the park by the time-honored southern route through the Thorofare Region in the southwest part of the park. Lt. J.W. Gunnison noted in his 1852 book The Mormons or Latter-Day Saints a “picture” that Bridger painted for him in words:

“…A lake sixty miles long, cold and pellucid, lies embosomed amid high precipitous mountains. On the west side is a sloping plain several miles wide, with clumps of trees and groves of pine. The ground resounds to the tread of horses. Geysers spout up seventy feet high, with a terrific hissing noise, at regular intervals. Waterfalls are sparkling, leaping, and thundering down from the precipices… The river issues from this lake…”

The lake appears to have hosted relatively few white men from the 1840s through the early 1860s, but prospectors and many others began to visit it again as early as 1864. And the lake stimulated stories that were “bigger than life,” including ones about huge fish. In 1867, journalist Legh Freeman of southern Wyoming somehow either found his way north to the lake or else talked with men like Henderson who had been there because Freeman wrote of it in his Frontier Index newspaper. The next year, he wrote more about Yellowstone Lake and according to historian Aubrey L. Haines, this account was so widely read that it influenced the creating of reputations of prospectors for “indulging in flights of fancy when recounting their adventures.” Said Freeman:

“This is the largest and strangest mountain lake in the world…surrounded by all manner of large game, including an occasional white buffalo, that is seen to rush down the perpetual snowy peaks that tower above, and plunge up to its sides into the water. It is filled with fish half as large as a man, some of which have a mouth and horns and skin like a catfish and legs like a lizard… [This lake] is so clear and so deep, that by looking into it you can see them making tea in China.”

Resorts a’comin’?

Fanciful tales of Yellowstone Lake that stretched the truth largely ended in 1869 and 1870 when the Folsom and Washburn parties received credit for the Euro-American discovery of the Yellowstone region and wrote more factual accounts. David Folsom described the lake as he perceived it when he arrived there in 1869, but his description reflects the problem of not being able to see the entire lake from one vantage point. In The Valley of the Upper Yellowstone: An Exploration of the Headwaters of the Upper Yellowstone River in the Year 1869, edited by Aubrey L. Haines, Folsom’s paean to the lake has great beauty and is worth quoting:

“Nestled within the forest-crowned hills which bounded our vision, lay this inland sea, its crystal waves dancing and sparkling in the sunlight as if laughing with joy for their wild freedom. It is a scene of transcendent beauty which has been viewed by but few white men and we felt glad to have looked upon it before its primeval solitude should be broken by the crowds of pleasure seekers which at no distant day will throng its shores.”

“How can I sum up its wonderful attractions?” said Nathaniel Langford of the 1870 Washburn party and first superintendent of the park. In “The Wonders of Yellowstone” featured in the June 1871 issue of Scribner’s Monthly, he wondered whether Yellowstone Lake’s islands and shores would someday be home to “villas and the ornaments of civilized life.” Upon seeing Yellowstone Lake for the first time, Langford was moved to write eloquently and truthfully:

“There lay the silvery bosom of the lake, reflecting the beams of the setting sun, and stretching away for miles, until lost in the dark foliage of the interminable wilderness of pines surrounding it. Secluded amid the loftiest peaks of the Rocky Mountains, [thousands of feet] above the level of the ocean, possessing strange peculiarities of form and beauty, this watery solitude is one of the most attractive natural objects in the world…now it lay before us calm and unruffled, save by the gentle wavelets which broke in murmurs along the shore. Water, one of the grandest elements of scenery, never seemed so beautiful before. It formed a fitting climax to all the wonders we had seen, and we gazed upon it for hours, entranced with its increasing attractions.”

Yellowstone Lake’s beauty enthralled dozens if not hundreds of early visitors. Dr. F.V. Hayden waxed poetic as he effervesced about it when his party arrived there on July 28, 1871, “Such a vision is worth a lifetime, and only one of such marvelous beauty will ever greet human eyes.”

Lt. John G. Bourke, who wrote On the Border with Crooke and traveled great distances with General George Crooke, shared Hayden’s delight with the lake, giving it his highest compliments:

“…and then, grandest scene of my life (emphasis added), there lay at our feet the unruffled brow of Yellowstone Lake, miles in length and breadth, guarded by giant mountains upon whose wrinkled brow rested the snows of Eternity. The only air was still in the presence of as much solemnity and majesty: a few geysers largely emitted puffs of steam and broke the otherwise absolute quietude of this vast seclusion.”

Quite early, it became apparent that Yellowstone Lake, and the park in which it was located, would eventually become a successful and famous summer destination. An 1871 visitor, Calvin Clawson, thought that the “Lake and vicinity” would someday become “the most desirable summer resort for the people of the United States and no doubt will attract many visitors from other countries.” He enthused about the lake by saying, “The eye must behold the glory thereof to believe, and even then, doubting, looks again.”

As early as 1872, the New York Herald declared that the Yellowstone country was already a great place to visit, touting “a night’s lodging in the virgin woods near Yellowstone Lake, where the air is fresh from heaven, and where they have a delicious frost every night in the year.” In 1873, the New York Times proclaimed that “it is only necessary to make the Park easily accessible to make it the most popular Summer resort in the country.” An 1882 visitor to Yellowstone Lake thought that “the time is not distant when this must become the Switzerland of America and the pleasure resort of the world.”

These and many other accounts predicted early to the world that the new national park would become a locus of great visitation, and they saw Yellowstone Lake as a central reason for that phenomenon.

In part two, to be included in the Spring 2008 issue, Whittlesey discusses the early byways in Yellowstone.

About the author

A prolific writer and sought-after spokesman, Lee Whittlesey was the Yellowstone National Park Historian at the time this series of articles was written. His 35 years of study about the region have made him the unequivocal expert on the park. Whittlesey has a master’s degree in history from Montana State University and a law degree from the University of Oklahoma. Since 1996, he’s been an adjunct professor of history at Montana State University. In 2001, he received an Honorary Doctorate of Science and Humane Letters from Idaho State University because of his extensive writings and long contributions to the park.

Post 007

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.