Byways, boats, and buildings: Yellowstone Lake in history, part 4 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2008

Byways, boats, and buildings: Yellowstone Lake in history, part 4

By Lee Whittlesey

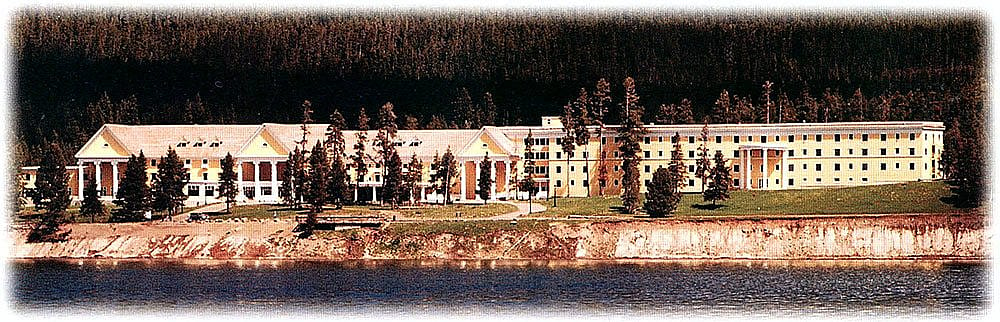

Lee Whittlesey’s manuscript of Yellowstone Lake, of which this is the final installment, was prepared last year to present the history of the lake area as the National Park Service plans a renovation of the site on the north shore. As Whittlesey puts it, “Accordingly, a history of the Lake Village was and is needed in order to provide background for how the present facilities and roadways came to be.” While there were many interesting buildings along the lake over the decades, this chapter takes special note of Lake Hotel—the grand hotel that can be seen today from nearly every vantage point around the lake.

Read Part 1

Read Part 2

Read Part 3

Early structures at Yellowstone Lake

Buildings existed in the lake area as early as 1875, and probably earlier. Indians frequented the shores of Yellowstone Lake during the summertime prior to the park’s establishment in 1872. In his 1880 annual report, Superintendent P.W. Norris mentioned the existence of “skin-covered lodges or circular upright brush heaps called wickeups [sic], decaying evidences of which are abundant near…the shores of Yellowstone Lake.”

Even before that, a July 4, 1872, issue of the New York Herald declared that the Yellowstone country was already a great place to visit, touting “a night’s lodging in the virgin woods near Yellowstone Lake, where the air is fresh from heaven, and where they have a delicious frost every night in the year.” The next year the New York Times proclaimed that “it is only necessary to make the Park easily accessible to make it the most popular Summer resort in the country.”

In 1887, the Yellowstone Park Association established a primitive tent camp in the vicinity of what would become Lake Hotel. So far almost nothing has surfaced about this tent camp and its operation, but apparently it operated during the seasons of 1881 – 1890. W.W. Wylie established a similar camp that same year according to early visitors. Thus, there were evidently two tent camps operating at Lake during those four years. The Wylie camp remained in operation continuously through 1916, when it became the Yellowstone Park Camping Company. In 1919, Lake Lodge was built on the Wylie site.

Lake Hotel

But Lake Hotel is probably the most recognizable structure on Yellowstone Lake today. Construction began in 1889 and was completed in 1891. The Yellowstone Park Association, a corporation that was owned and operated by the Northern Pacific Railroad, chose the site. At that time, the hotel was less visible from vantage points around Yellowstone Lake because it stood in a thickly forested spot. (Today, those trees are gone and this openness makes the hotel more easily visible from other places around the lakeshore than it was in early days.)

Lake Hotel—where the price of a room was $4 per night and dropped to $3 after six days—was originally a “nondescript clapboard” building, erected merely to appease the need for overnight accommodations. Because it was cheaply and not skillfully built, repairs were necessary in 1894 and 1897, and in 1900, the entire building was re-plastered, repainted, and re-calcimined.

The big renovation in 1903–1904 was designed by, and its construction overseen by, architect Robert Reamer at the same time his crews were building the new Old Faithful Inn forty miles away. The new look gave the hotel the colonial styling that it still has today. With its elegant changes, the hotel quickly was styled the “Lake House” or the “Lake Colonial Hotel,” but in time the name reverted to Lake Hotel. A 1911 Union Pacific Railroad brochure rhapsodized about Lake Hotel:

“The Colonial Lake Hotel, situated on the north shore of this grand mountain lake, overlooks the lake nearly 8,000 feet above sea level. Snowcapped mountains surrounding it are very attractive. The Colonial Hotel is modern in every way and has more than 250 rooms, many with private bath. A more restful place cannot be found in the park. Launches and row boats are ever at command, and the best of fishing is found in the lake outlet. Those having time usually stop an extra day at this hotel, while many remain here the greater part of the season.”

Passing the time at Lake Hotel

At Lake, visitors engaged generally in quiet activities. One of the things to do there, besides walking along the lake shore or going fishing or boating, was to visit the dump behind the hotel in order to see bears feeding on garbage. In 1891, a visitor experienced what was probably the very first year of the dump’s existence and recorded an early episode of the long abuse of park bears by park employees:

“Off we go, walking, running, flying through those woods in the direction of that bear. There he is! A fine two year old animal, up a tree, with two coach drivers [Joe and Hicks] after him with a rope, and a third driver, in a neighboring tree, prodding him down with a long, heavy pole. It is a holiday for those bold young drivers, and they have been after that bear since early morning. How they enjoy the sport; tis fun for all but the poor bear, who does not dare to come down among the crowd… Now look out drivers, if he gets near enough to strike a blow with his paw, it will be many a day before you will manage a fourin- hand [stagecoach]. Up he goes, like a flash, [on] one side of the tree, and ‘Joe’ is clinging to the other side, not two feet away. When the danger is over, a lady’s voice rings out sharp and clear, “Joe, you come down, don’t you let that bear eat you…”

One visitor was badly mauled there by a bear in 1902 when he attempted to pet a bear cub right in front of its mother. In 1903, Mrs. N.E. Corthell saw “women in party silks and loaded with diamonds” strutting out to watch the bears feeding.

In 1922 – 1923, architect Reamer added a four-story extension to the east side of Lake Hotel that contained 122 bedrooms and sixty-six bathrooms. Workmen encountered a geologic obstruction in the ground—a huge rock—and compensated for it by building the wing at a three-degree angle from the original structure. At the same time, Reamer replaced the hotel’s dining room, remodeled the kitchen, and added a fireplace and mantel to the lobby, with a mesh spark screen decorated with pine tree ornamentation. He also converted the space over the old dining room into what the company soon called the “Presidential Suite,” probably as much for company president Harry Child to stay there as for later U.S. presidents such as Calvin Coolidge and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Reamer’s last renovations to Lake Hotel occurred in 1928 – 1929, when he enclosed a portion of the hotel’s porte cochere to provide a larger lobby and built a new porte cochere farther east. He also added the hotel’s large one-story lounge—a solarium-type room with a grand piano—extending toward Yellowstone Lake, seventy new light fixtures, and a wall-hung drinking fountain to the right of the fireplace.

In 1927, President Calvin Coolidge stayed in the Lake Hotel, probably in the “Presidential Suite” that Robert Reamer had added. Park Superintendent Horace Albright met “Silent Cal” in the new lounge overlooking Yellowstone Lake. “After a lengthy silence,” wrote Albright, the president “said he had come to a decision. I hoped it was about my suggestion for adding the lovely Teton mountain area to Yellowstone or some such vital question. Not so. Coolidge stated that he wanted to change the itinerary to stay one more day at Lake Hotel so he could take in a new fishing area that sounded good.”

Closed for war…and Depression

World War I caused company officials to keep Lake Hotel closed during the seasons of 1918 and 1919. Workmen began repairs to the hotel in late 1919 that included adding a covered entry to the front of the hotel and a concrete walk to replace the wooden porch. The hotel reopened in 1920.

During the Great Depression, company officials closed Lake Hotel from 1932 through 1936. It reopened in 1937 after receiving new shingles on its roof and a new coat of its familiar yellow paint. At the same time, the hotel’s boilers—which originally powered the steamboat E.C. Waters—were converted to oil. In 1940, workmen removed the north wing of the hotel and began construction of cottages there similar to the ones at Mammoth Hotel. However, because of decreased travel and rationing of resources during World War II, officials closed the hotel again from 1942 through 1946.

Lake Hotel today

Before long, the old Yellowstone Park Company had allowed Lake Hotel and many other park facilities and services to become greatly rundown. During the 1950s, the company even considered razing the hotel, but decided instead to renovate 133 rooms in the east wing, as well as the kitchen and dining room. They also changed the first floor decor to “birch veneer moderne,” giving the hotel a starkness that was characteristic of that decade and which essentially lasted until 1984.

TWA Services, Inc., which took over the park hotel concessions in November 1979, was committed to great improvements at Lake Hotel. Thus, during the period 1980–1984, the new company, in partnership with the National Park Service, engaged in a thorough remodeling of Lake Hotel, restoring it, as historian Tim Manns noted, “to what we’d like to think of as the 1920s.” In 1991, the hotel celebrated its 100th anniversary with a gala costume ball.

Final word on Yellowstone Lake

When Dr. F.V. Hayden and his party arrived at Yellowstone Lake on July 28, 1871, he wrote:

“The lake lay before us, a vast sheet of quiet water, of a most delicate ultramarine hue, one of the most beautiful scenes I have ever beheld. The entire party were [sic] filled with enthusiasm. The great object of all our labors had been reached, and we were amply paid for all our toils. Such a vision is worth a lifetime, and only one of such marvelous beauty will ever greet human eyes.”

Ever since humans first beheld Yellowstone Lake, it has had that same effect on travelers—and Lake Hotel has clearly played a significant role in the visitor experience. For those who’ve never toured Yellowstone National Park, check out www.nps.gov/yell and begin planning your trip today. In addition, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Draper Natural History Museum is the perfect complement to the Yellowstone experience.

About the author

A prolific writer and sought-after spokesman, Lee Whittlesey was the Yellowstone National Park Historian at the time this series of articles was written. His thirty-five years of study about the region have made him an unequivocal expert on the park. Whittlesey has a master’s degree in history from Montana State University and a law degree from the University of Oklahoma. Since 1996, he’s been an adjunct professor of history at Montana State University. In 2001, he received an Honorary Doctorate of Science and Humane Letters from Idaho State University because of his extensive writings—many available through the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Museum Store—and long contributions to the park.

Post 010

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.