The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara people and the Flood Control Act of 1944 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2005

We’re not here to sell our land: The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara people and the Flood Control Act of 1944

By Marilyn Cross Hudson

Editor’s Note:

Marilyn Cross Hudson is the director of the Three Affiliated Tribes Museum in New Town, North Dakota, and is a member of the Plains Indian Museum Advisory Board. The excerpt that follows is from her presentation at the Plains Indian Museum Seminar, Native Lands and the People of the Great Plains, September 29–October 2, 2005. She shares a personal look at the Garrison Dam, part of the larger Missouri River Basin Project that affected the lives of the people in the area.

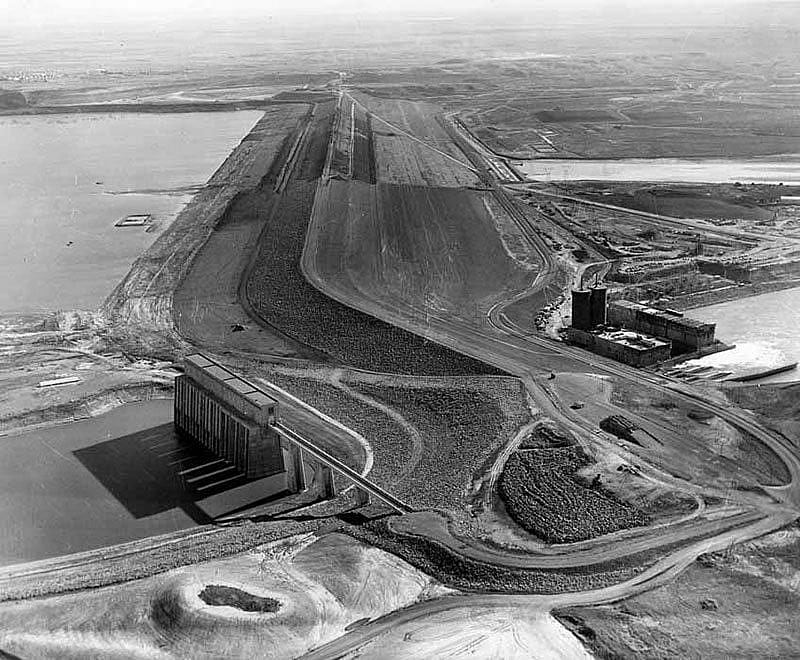

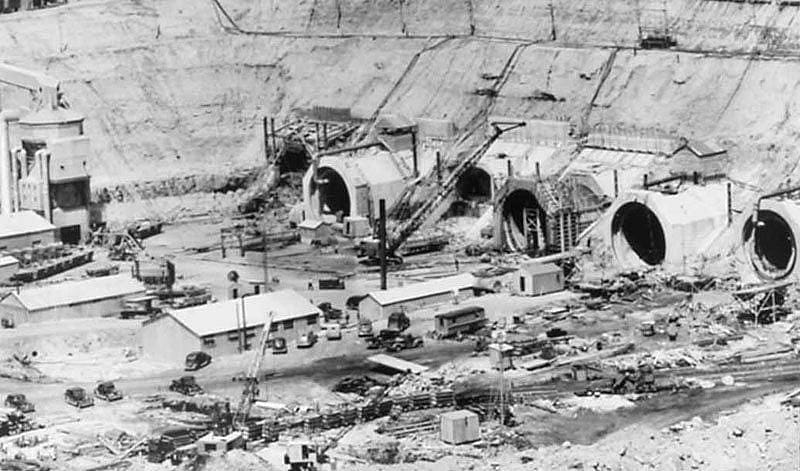

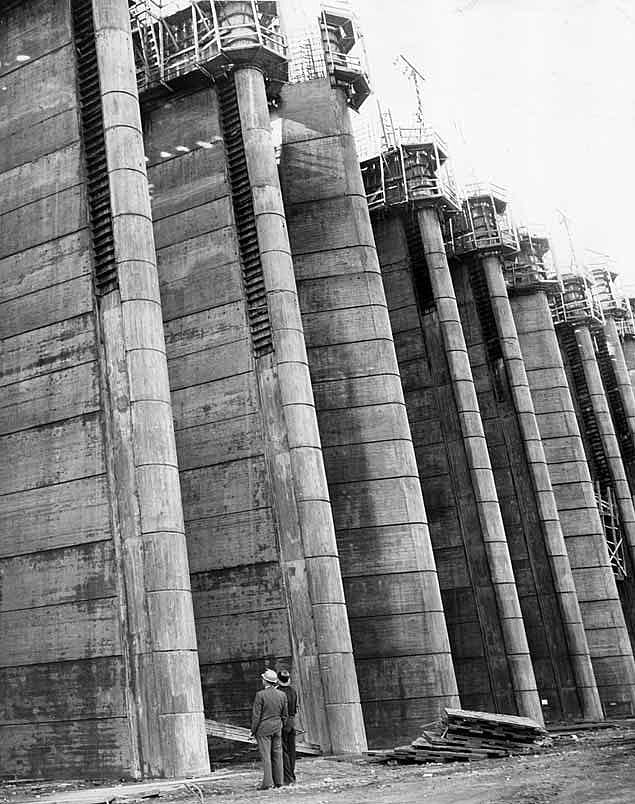

The Missouri River Basin Project was authorized in 1944 to develop the water resources of the Missouri River and its tributaries. The project included provisions for constructing 112 dams, seven of which were “mainstem” dams on the Missouri, the others on tributaries. The idea was to increase irrigation, hydroelectric generating capacity, flood control, fish and wildlife preservation, industrial and municipal water supplies, and develop recreational facilities.

One of the main-stem dams was the Garrison Dam project in North Dakota. The dam site and the resulting Lake Sakakawea reservoir meant those on the Fort Berthold Reservation—some 349 families—would have to be relocated from the fertile land on which the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara tribes had lived for centuries. Marilyn Hudson was a teenager when her family became one of those who had to move to make way for the dam. What follows is her story about the project, its effect on those involved, and how tribal representatives sought to halt the dam construction through their testimonies before Congress.

The Fort Berthold Reservation on the upper Missouri River is a land which no longer exists, but is a place in time to which I, and others of my generation, am irrevocably tied spiritually and physically. It is the land of our birth and the land of our fathers and their fathers before them. It is the land which nourished and sustained the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara people from a time well before Columbus to the twentieth century.

The Three Affiliated Tribes are known as permanent dwellers of the Northern Plains—agriculturalists who adapted many varieties of corn, beans and squash to this harsh growing climate. Early on, there were large populations of these peoples inhabiting the area, but by 1880, less than 1,000 people remained huddled in a makeshift village at a place called Like-a-Fishhook on the upper Missouri River. Epidemics of smallpox and cholera, the loss of buffalo, warfare, and the nation’s Manifest Destiny doctrine contributed to their decline and the loss of their way of life.

Still, the population had rebounded by the early 1900s, and the buffalo culture was replaced by the horse and cattle culture. By 1944, although farm and ranch cash income was minimal, the people were living quite well since the land itself was so productive.

In the closing days of 1944, the U.S. Congress passed the Flood Control Act (Public Law 78-534), which authorized the construction of the Garrison Dam on the Missouri River. This news was a punch that took the breath away and broke the hearts of the people. They couldn’t believe their beloved lands would be flooded—“their inherent property from time immemorial and in no sense given to them by any human power” as stated in a 1945 tribal resolution.

The next six or seven years would be marked by intense opposition to the dam as negotiations began with the federal government. Lines of defense included the right of original occupancy; the sanctity of treaties; provisions of the Louisiana Purchase; the Dawes Act, which provided for allotments of lands; stewardship theories; trust status of Indian land; lack of Congressional power to condemn tribal land; certificates of competency; sovereignty; and humane treatment of citizens. They were the generation of my parents who bore the full brunt of this terrible blow. Today’s tribal leaders identify this time as the second most traumatic event in the history of their people; the 1837 smallpox epidemic, which killed 90 percent of the Mandan and Hidatsa populations in the upper Missouri River villages, was the first.

Public Law 437 (1949), referred to as the Taking Act, stated that the government must compensate for the lands they acquired from the Indian people. However, at every hearing and meeting, no matter its location, the Indian people simply refused to sell their land. Finally, the government said, “either sell your land or it will be condemned and you may receive even less than what is being offered.”

Ten people faced this dilemma as they traveled from the Fort Berthold Reservation to Washington, D.C. in April 1949. Traveling by train or bus, lodging in meager quarters, and eating in diners sympathetic to Indian people, these ten were to present testimony in a hearing before the House Committee on Public Lands. The committee’s purpose was to purchase 155,000 acres of Fort Berthold Reservation lands for the creation of the Garrison Dam project. The hearing would determine the value of the land to be taken from the Indian people.

Those representing the tribe were chosen for their areas of expertise. Mr. Packineau spoke about hunting; Mr. Little Soldier about ranching, and Mr. Heart about coal mining. Other subjects included fur-bearing animals in the area, timber, farming, and tribal history. They all did their own research and wrote their own speeches. The records tell about Mr. Heart lying on the floor of the hotel room with a pencil and paper writing out this testimony. I think we can conclude that there were probably several of the men sharing a small room in a low-budget hotel without the standard desk you find today.

The delegation returned home on May 1, 1949, already sensing their testimony was undoubtedly to no avail. I wonder what their thoughts were as they looked out the window as the train rolled westward. They knew the battle had been lost, and that even as they moved along, construction crews were already hard at work building the dam.

Three years later, in 1952, Tribal Chairman Martin Cross issued a statement in hopes of delaying the flooding of the Three Affiliated Tribes land. It read, in part,“The gates of the Garrison Dam are scheduled to be closed on July 1, 1953, so it is obvious that the time element is against us. Can you do something for us before the floodwaters close over our heads?” He was referring to the lack of coordination between the agencies—the Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and other officials who were managing the relocation effort. Despite Chairman Cross’ plea, thousands turned out June 11, 1953, to join President Dwight D. Eisenhower in celebrating the Garrison Dam’s closure.

During the Missouri Basin projects era, the Three Affiliated Tribes membership suffered the highest percentage of land loss among Missouri River Basin tribes (approximately 95 percent). However, they were not the only Native peoples affected by the Flood Control Act of 1944. Before the projects were completed, twenty-three different tribes would suffer similar fates. While the details varied for the Sioux, the Crow, and the Northern Cheyenne, the results were invariably the same. It would be some 48 years, however, before Congress enacted legislation acknowledging the fact that the U.S. Government had not justly compensated the tribes at Fort Berthold and Standing Rock Reservations when it acquired their lands for the Garrison Project. According to the 1992 legislation (Three Affiliated Sioux Tribes and Standing Rock Sioux Tribes Equitable Compensation Act), they were indeed entitled to additional compensation. For the Three Affiliated Tribes, the decision was a long time in coming.

For further reading:

Read more about the Plains Indian Museum and Plains Indian culture.

Read more about Plains Indian tribes.

Dammed Indians: The Pick-Sloan Plan and the Missouri River Sioux, 1944 – 1980. Michael L. Lawson. Norman, Oklahoma and London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1982 and 1994.

Coyote Warrior: One Man, Three Tribes and the Trial That Forged a Nation. Paul VanDevelder. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2004.

There are a host of websites about this project. Simply enter “Garrison Dam” in your browser window.

While not addressed specifically by symposium attendees, this story about Rocky Ford, Colorado, typifies the complexity of Watering the West.

In April 1949, ten representatives from the Fort Berthold Reservation testified before Congress against building the Garrison Dam. Excerpts from four of those testimonies are printed here.

Martin Cross

As Tribal Chairman of the Three Affiliated Tribes and First Vice President of the National Congress of the American Indian, Martin Cross became one of the first Indian leaders of the modern era to use the law and the U.S. Constitution to fight his tribe’s battles in the U.S. Congress. In his testimony, Cross remarked, “This is not the first time that public interest has sought to acquire the lands of the Fort Berthold Indians. It has been done before in the 1866 Treaty which opened the territory for railroads, and by subsequent Executive Orders of 1870 and 1880 which reduced some more of our territory without our consent, until now we have only 600,000 acres left of our original 9 million acres. Is that not depreciation enough? No! The public demands some more. Do you argue why we protest against this further demand?”

Anna Wilde

At age 78, Mrs. Anna Wilde was the eldest and only female member of the Three Tribes 1949 delegation to Washington, D.C. According to her testimony, Wilde explained, “Our ancestors and forefathers gave us our land and homes which our United States Government in peace treaties promised would be ours forever. From her (the mother’s) garden, the harvest was a large crop of corn, beans and squash. It was from such a supply that she furnished seeds to the pale-faced stranger who had come into our midst. Along the Missouri River bottom land grow different kinds of berries which are picked and preserved. We mothers continue in prayer for humane justification. So that again we may take heart and feel we may rightfully hold up our heads to sing, ‘My Country, “Tis of Thee.'”

Carl Whitman, Jr.

Carl Whitman, Jr., a 36-year-old Mandan from the Lucky Mound District, was a progressive who envisioned economic development. In his testimony, he said, “We see our best land being taken from us and we know not yet what our future will be. We kept our promise and have worked to build up a strong and growing cattle industry and steadily expanding agricultural program. Just as we were in sight of economic independence, you began to build a reservoir and to take away the heart of our reservation.”

Carl Sylvester

Carl Sylvester was a 62-year-old Hidatsa from Elbowoods, educated at the Carlisle School. I remember him as being rather mysterious—a loner that we did not really know. He was also well educated in the East, and most thought him a very smart man—maybe even a lawyer. His testimony referred to the 1851 treaty of Fort Laramie, Wyoming where the Fort Berthold Indians were assured by the federal agents that their lands would be secured and would be free from danger of dispossession in the future for any reason whatsoever. Sylvester noted, “This understanding was firmly established from that time to this, even in the light of repeated and glaring violations on the part of the government and its citizens. The Three Affiliated Tribes have kept their part of the treaty and deserve the utmost consideration. There is no excuse on the part of the government to take steps at intimidation and instilling of fear in them about property confiscation. We were not at any time at war with the government.”

Post 026

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.