Col. Cody, the Rough Riders, and the Spanish American War – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 1998

Col. Cody, the Rough Riders, and the Spanish American War

By Paul Andrew Hutton, Guest Author

Former Executive Director, Western History Association

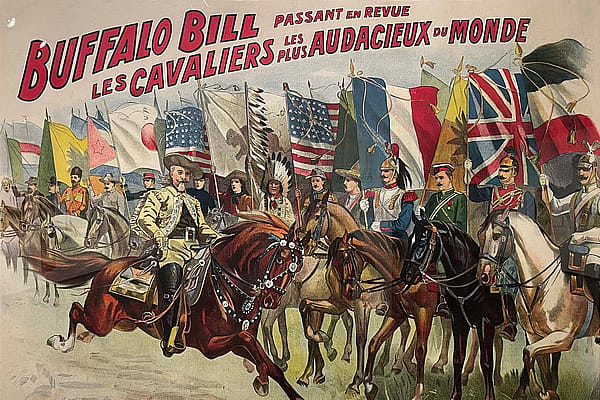

Buffalo Bill Cody’s Congress of Rough Riders of the World began the 1898 season with a performance in the grand amphitheater at Madison Square Garden, New York City. There was a pleasing familiarity to the great extravaganza-the Indian attack on the wagon train, crack shot Johnny Baker, Cossacks on horseback and a whirling dervish, the amazing Annie Oakley, and the historic spectacle of Custer’s Last Stand! The huge crowd loved it all, but the greatest ovation of the evening went up for a new feature, a small band of battle-scarred veterans from Cuba.

“Viva Cuba libre!” went up the cry from hundreds of throats as the white-clad Cuban rebels rode into the arena unfurling their red, white, and blue flag with its bald single star. The Wild West band played the Cuban national hymn and the crowd shouted itself hoarse. Out galloped a color guard carrying Old Glory and again went up the shouts of “Cuba Libre!” It was clear to all that evening that the destinies of the Cuban people and the American people were to be forever intertwined. Buffalo Bill had seen to that in a brilliant moment of topical showmanship. It had been six weeks since the U.S. battleship Maine had mysteriously blown up in Havana harbor, killing 260 Americans. For over a generation Americans had watched in horror as the Spanish imperialists had brutally suppressed Cuban independence efforts, killing thousands of Cuban civilians. Long fuming with indignation, American now demanded a war to liberate Cuba and avenge the Maine.

The master publicist John Burke had traveled to Cuba in 1897 and, despite the watchful eye of Spanish agents, had managed to recruit 14 Cuban rebels for Cody’s Wild West. The men had all been wounded in battle, one having lost a leg and another an arm. They were commanded by Lt. Col. Ernesto Delgado who had himself twice been wounded. “Colonel Cody has performed a distinct national service in bringing these Cuban heroes to the United States,” noted the World. “They give us an opportunity to see the kind of men who make up the insurgent army.” The people of New York were clearly impressed with what they saw.

Cody’s presentation of the Cuban insurgents could not have appeared at a more opportune time. War hysteria was sweeping the country, fueled in no small part by the same New York newspapers-the so-called “yellow press”-chat now lavished ink on Cody’s Wild West. Heroic portraits of the Cuban rebels appeared regularly, with emphasis placed on how much like Americans they were.

In a remarkable interview with Cody in the World on April 3, 1898 the headline boasted, “How I could drive Spaniards from Cuba with 30,000 Indian braves.” Lt. Col. Delgado was quick to add that such a force under Cody could “take Havana in one dashing charge.” Cody assured the World “that every Indian would be loyal to the American flag.” He had no doubt that by working in conjunction with the Cuban rebels his Indian force would finish off the Spanish in just 60 days.

It soon became clear that Buffalo Bill would get his chance in Cuba. President William McKinley, although opposed to war himself, could not resist the public pressure to take action. He finally demanded that the Spanish grant Cuban independence, and when they refused he asked Congress to vote on military intervention to assist the rebels. On April 19, 1898, a joint resolution calling for armed intervention passed Congress, and on April 23 Spain declared war on the United States.

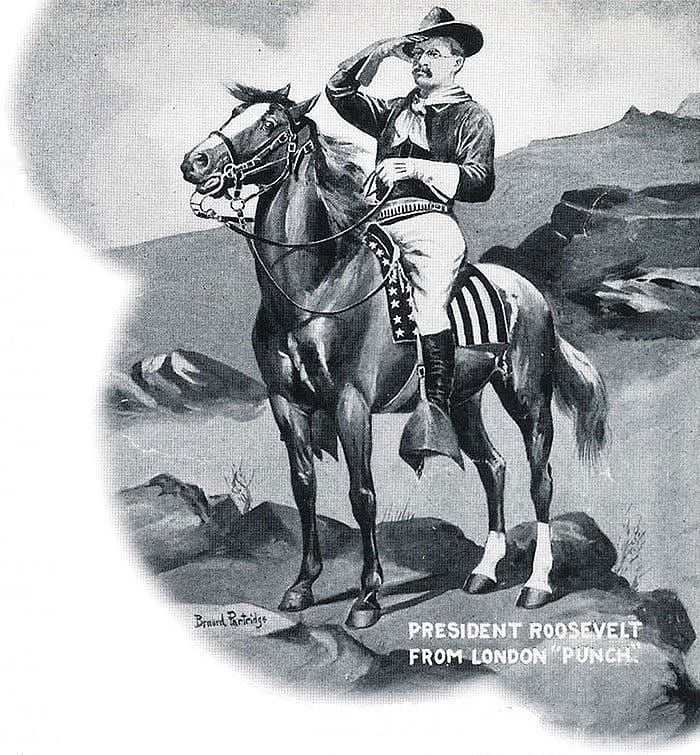

On April 25 the U.S. declared war, and on that same day Burke declared that Gen. Nelson A. Miles, commanding general of the U.S. Army, had asked Cody to join him as a scout. “Buffalo Bill will come back again,” Burke declared, “but he will leave a record behind him that neither Cuba nor America will be apt to forget, while Spain will remember him with a groan.” The next day the New York Herald featured Cody alongside other notable men—Theodore Roosevelt, Joseph Wheeler, Fitzhugh Lee, Charles King—who would hold commands in the expanded volunteer army. Roosevelt, the assistant secretary of the Navy, was to become a lieutenant colonel in a unique regiment of western “cowboy cavalry.” Cody would “serve on the staff of Major General Miles as chief of scouts” with the rank of colonel.

Ironically, despite all of Burke’s press agentry, Cody thought the war a mistake. On April 29 he wrote his friend George Everhart: “I will have a hard time to get away from the show–but if I don’t go–I will be forever damned by all–I must go–or lose my reputation. And General Miles offers me the position I want. George, America is in for it, and although my heart is not in this war–I must stand by America.” Cody, who held the Congressional Medal of Honor, did not need to prove either his courage or his patriotism in 1898. As a 52-year-old veteran of the Civil War and Indian Wars, he was a bit long in the tooth for campaigning in tropical climes. Even more pressing was his responsibility to the 467 employees in his Wild West. He delayed joining Miles while the show moved on to Philadelphia, Washington, and Hartford. Still, he made preparations to depart, sending two horses—Lancer and Knickerbocker—to the general in anticipation of joining the campaign. Cody waited too long for, as he had predicted, the war was over quickly. On July 1 American troops including Colonel Roosevelt’s Rough Riders-captured the San Juan Heights above Santiago de Cuba.

On July 3 the Spanish fleet was destroyed by American naval forces near Santiago and on July 17 the city capitulated. Miles sailed for Puerto Rico on July 21 and sent for Cody: “Would like you to report here, taking first steamer from Newport News.” Cody wired back that it would cost $100,000 to shut down his show, and wondered if he should not wait to see how the ongoing peace negotiations turned out. Miles cabled back a succinct one-word response: “Yes.”

That Cody had every intention of joining Miles is evident from a private letter he wrote his friend Moses Kerngood on August 3, 1898: “I am all broke up because I can’t start tonight,” he wrote. “It’s impossible for me to leave without some preparations and it will entail a big loss and my fortune naturally affect. But go 1 must. I have been in every war our country has back since bleeding Kansas war—in which my father was killed—and must be in this if I get in at the tail end.” But on August 12 an armistice was signed with Spain and the war was over. “I have been in every war since I was old enough, but this one,” Cody lamented, “and I did all I could to get into this.” Even if Cody missed the fighting, his connection with the Spanish-American War did not end with the armistice. The great hero of the hour was Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, whose Rough Riders emerged as the most famous regiment of the war. The regimental nickname had been borrowed from Cody’s “Congress of Rough Riders of the world” by the press corps. They quickly identified Roosevelt’s western cavalrymen with Cody’s arena cowboys and the alliterative title stuck. At first Roosevelt opposed the name, fearing that the public would never take the regiment seriously, considering it “a hippodrome affair.”

“Don’t call them rough riders, and don’t call them cowboys,” he begged the press. “Call them mounted riflemen.” Everyone ignored him and he soon relented to the inevitable, perhaps taking solace in the fact that he had used the term before Cody officially adopted it in 1893. In August 1886 he had written a friend from his North Dakota ranch that “I think there is some good fighting stuff among these harum-scarum roughriders out here.”

By September 1898 the name Rough Riders had become so identified with Roosevelt that Cody jokingly suggested that he might change the title of his show. “You know I originated the name “Rough Riders,” he declared. “I have been calling my men ‘Rough Riders’ for 10 years. Next year I am going to call them smooth riders. Why should I call them rough—They’re the smoothest riders on earth.” Humor aside, Burke’s press releases continually emphasized the fact that the term “Rough Riders” had originated with Cody’s show and not with Roosevelt’s regiment.

Burke moved quickly to exploit both the notoriety of Roosevelt’s Rough Riders and the connection between them and the show. Sixteen veterans of Roosevelt’s regiment were hired to perform during the 1899 season. Among those recruited was Cherokee Rough Rider Tom Isbell who had been the first to draw Spanish blood at the battle of Las Guasimas. Despite seven wounds Isbell had somehow survived. Before joining the show he had returned to Oklahoma and killed a rival who had been courting his girlfriend while he was away in Cuba. Another star recruit for the show was a bantam bronc buster from Indian Territory, Little Billy McGinty.

“He never had walked a hundred yards if by any possibility he could ride,” Roosevelt said of the master horseman.

Replacing “Custer’s Last Stand” as the grand historic spectacle of the 1899 and 1900 seasons was the “Battle of San Juan Hill.” Scripted by Nate Salsbury, the battle usually came as the show’s finale. It was presented in two scenes. The first was the bivouac of the American troops the night before the battle-Rough Riders, artillerymen, regulars of the black Ninth and Tenth Cavalry (buffalo soldiers), and Cuban rebels. The second scene presented the charge up the hill against the Spanish blockhouse and rifle pits (represented in a massive painted backdrop). Breathless press releases described the final heroic moments as “Roosevelt of the Rough Riders, on horseback, presses to the foot of the death-swept hill and calling upon the men to follow him, rides straight up and at the fortressed foe. There is a frantic yell of admiration and approval as the soldiers—white, red and black-spring from their cowering positions of utter helplessness and follow him and the flag.”

It is difficult to calculate the value that this spectacle had on the political fortunes of Theodore Roosevelt—but it must have been considerable. It boosted Roosevelt’s hero status, keeping his military exploits vividly before the public as he served as governor of New York and then ran for the vice-presidency in 1900. In September 1898, while TR was locked in a tight race for the New York governorship, Cody weighed in with a succinct and helpful estimation of his friend: “They don’t make any better men than Teddy Roosevelt.”

For the 1901 season, the Chinese Boxer Rebellion was used as the Wild West’s historic spectacle, replacing the Battle of San Juan Hill. Roosevelt was hardly forgotten, however, as The Rough Rider, a publicity courier distributed for the show, featured a large drawing of Buffalo Bill and Colonel Roosevelt riding side by side.

The following season, with President McKinley assassinated and Roosevelt the new President, the Battle of San Juan Hill returned as a permanent feature of the show.

Roosevelt never forgot the debt he owed Cody. In 1904 he wrote his son Ted from the White House, noting that Buffalo Bill had come to lunch with him. “I remember when I was running for Vice-President I struck a Kansas town just when the Wild West show was there,” he reminisced. “He got upon the rear platform of my car and made a brief speech on my behalf, ending with the statement that ‘a cyclone from the West had come; no wonder the rats hunted their cellars! “‘

In February 1917, a month after Cody’s death, Roosevelt lent his name to an effort to raise a statue on Lookout Mountain, above Denver, to his old friend. “Buffalo Bill was an American of Americans, and his memory should be dear to all Americans,” noted the former President, who would himself die almost two years to the day after Cody, “for he embodied those traits of courage, strength and self-reliant hardihood which are vital to the well being of our nation.” It was a fitting epitaph for both of those bold Rough Riders.

Post 039

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.