“It’s Just a Bird”- the Endangered Species Act

In recent years, we’ve heard increasing criticism of the Endangered Species Act and the inconvenience and potential economic costs of protecting native wildlife species, such as prairie dogs, sage grouse, and wolverine. On the other hand, many people around this country and the world point to our rich wildlife conservation heritage as a great achievement and source of American pride. Thanks to the foresight and Herculean efforts of people like George Bird Grinnell, Theodore Roosevelt, Gifford Pinchot, Aldo Leopold, and Richard Nixon, among many others, America is a beacon for conservation and environmental stewardship around the world. Unlike Europe, and most of the first world nations, the United States has worked to conserve and even restore a large component of our native wildlife heritage through habitat protection and science-based management strategies, in part through the Endangered Species Act. And we have done so while maintaining what is still a high standard of life for our people.

That’s why it is puzzling to hear some people decry our efforts to conserve and sustain our wildlife heritage. Of course, we want to keep our economy strong and improve the standard of living for our people while protecting our natural heritage. But as we continue to expand our footprint, and “tinker” with our environment, we should keep Aldo Leopold’s simple, powerful words in mind: “To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.” –Aldo Leopold, c. 1938. Joni Mitchell reminded us about the pain of losing what we can’t get back: “Don’t it always seem to go, that you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.” –from the song Big Yellow Taxi, 1970. Along the same lines, I’ve heard my colleague Chuck Preston say: “Every species represents a unique solution to a unique suite of environmental challenges—and to lose a species is to lose solutions.”

I perhaps flatter myself by thinking I’m an intelligent tinkerer. I don’t recall that I’ve ever discarded any cogs or wheels, although I will confess to disposing of some wires and switches, a screw or two maybe, with the caveat that I’ve confirmed the proper operation of the affected equipment before disposal of said parts. Like Aldo Leopold, I’ve found value in the cogs and wheels of nature that perhaps can’t be measured with the typical yardstick of economics, and like Joni Mitchell, I find it difficult to predict the impact of loss. The world will continue to turn if the sage grouse disappears from the planet. But, the loss of the sage grouse means that we’ve lost an iconic western landscape habitat—the sagebrush-steppe—that has supported wildlife and people for more than 10,000 years in this part of the world.

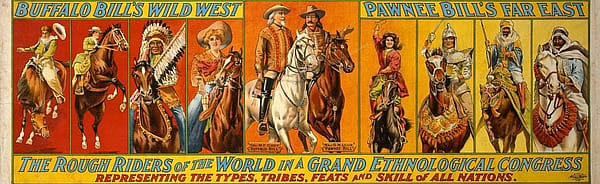

I look back to other circumstances, when we’ve been challenged to decide the fate of other species. The bison, centerpiece of the Wyoming flag, comes immediately to mind. Recall the grizzly bear, ironically the centerpiece of California’s flag, but which doesn’t roam wild there anymore. The bald eagle, symbol of our country, was nearly extinct when the Endangered Species Act came into existence and likely played a significant role in arguments for passing that legislation. The world would have continued to turn if any or all of these creatures had gone extinct. What good are they, if you can’t drill ’em, mine ’em, or find some way to turn ’em into money?

Well the fact is, tourism is the number two industry in Wyoming and there’s room for growth. But only if folks from around the globe can expect to have a chance to see America’s Wild West in some form that resembles what’s been marketed to them for the past hundred years. Why do we live in Wyoming; what is it that we value here that we can no longer find in most of the rest of the world?

I guess the central question becomes, “Does everything have to have a monetary value to be valuable?” This question has been posited by naturalists ever since the first one. For myself, I’ve watched the sage grouse perform its early morning mating dance, heard the glubbity sound of its call. I’ve been startled and thrilled by a flock taking to the air as I traversed the wild prairie. I’ve heard the howl of wolves as I sat by the campfire, hunted through the woods over the tracks of grizzly bears whose feet were bigger than my own, seen them looking at me from JUST OVER THERE! I’ve faced moose and bison from yards away and hoped they didn’t take a notion to be contrary.

I don’t want a tame Wyoming. I don’t want all the trees to be in a tree museum, and pay a dollar and a half just to see ’em, as Joni Mitchell predicts in her song. We could pave paradise and the world would still continue to turn. But pavement will not sustain us.

Thank you to Dr. Charles Preston for his collaboration in writing this post.

Written By

Phil Anthony

Phil Anthony is the Operating Engineer at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. He has been in the HVAC-R service industry for over 30 years (fifteen of them at the Center.) Phil holds journeyman certificates through the City and County of Denver as a steamfitter and a refrigeration technician, and a low-voltage electrical technician’s license with the state of Wyoming. An artist, poet, musician (sort of,) and avid outdoorsman, Phil has been called "a true renaissance man."