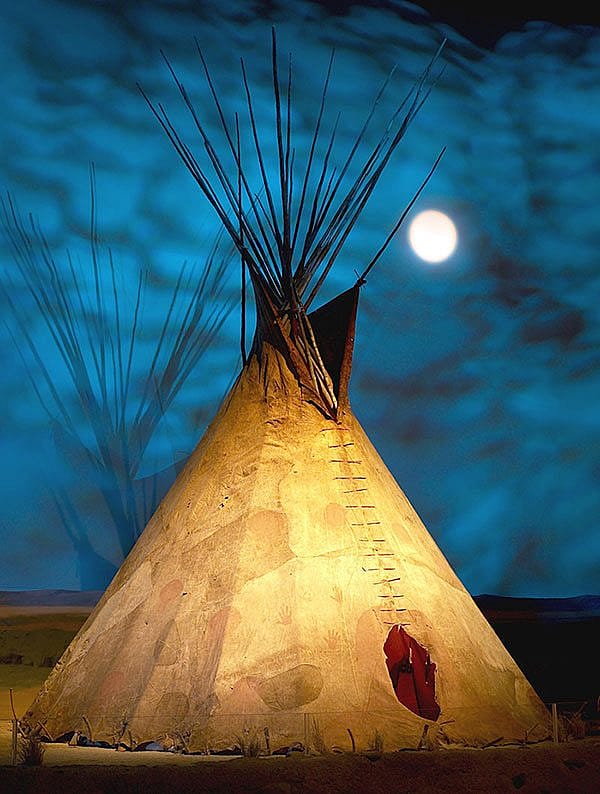

I’m Glad I Don’t Live in a Tipi

The solstice has just passed. Snow on the ground muffles sound, but it’s more quiet right now anyway. The world’s creatures are lying low, huddled for warmth as the mercury dips below zero. The museum is closed for three days a week this time of year, and many of the staff are out on holiday too, so it’s as quiet inside the building as out. There’s a stillness to the earth that only happens during winter. It’s a time for reflection, introspection, and contemplative creativity. ‘Tis the season when I think of my own little work bench as “Santa’s Workshop”…

The wind was howling the other night, and the temperature was bitter cold. At moments like that, I often say to my wife, “I’m glad we don’t live in a tipi.” She agrees. Don’t get me wrong—for a pre-industrial nomadic society the tipi is about as good as it gets. It’s portable and takes the edge off even the worst weather. But when the wind is blowing snow at speeds of fifty or eighty miles an hour, that hide has got to be shaking and flapping, little snow drifts appearing wherever outside air is coming in, and at times like that the occupant has to be hoping the thing stays standing. During the summer we erect tipis, as well as modern pole tents, on museum grounds. In a high wind the tents are much more likely to come down than the tipis, but even the tipis sometimes shift or collapse too. Maybe we’re just not as good at putting up a tipi as someone whose life depends on it is.

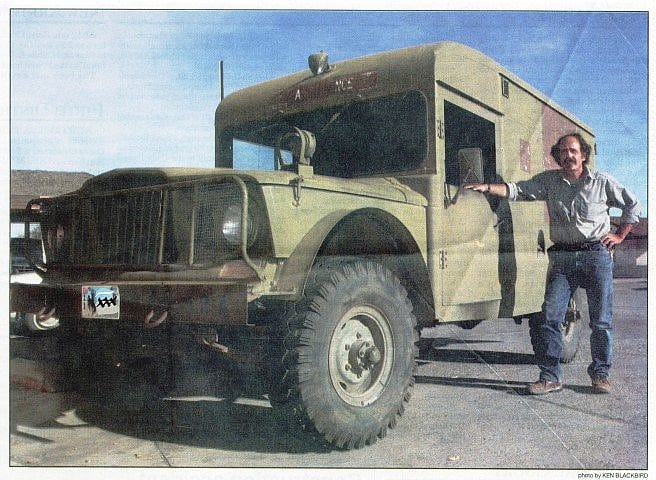

I used to fantasize about living a nomadic life—not in a tipi but in my old Army ambulance. It gets pretty noisy with all its rattling and banging when the wind is blowing, but I know it won’t collapse. And it gets pretty cold inside, but it does have a couple of inches of insulation in the walls—something a tipi can’t provide. After a cold winter night in the Jeep I’ll wake up to a thick layer of frost on the walls. I’ve slept in a tent too—not in the depths of winter, but late autumn can certainly throw some nasty weather at you. I’ve had my tent buried under the snow. I’ve had to force my complaining feet into frozen boots.

The hardest moment of the day in winter camp is the moment when one commits to getting out of bed.

I suspect most of the pre-reservation Native American decorative art we see was produced during the winter in a tipi. What better way to spend a frigid day than inside your shelter with a little fire going, doing beadwork or carving a pipe, or painting a winter count on a hide. The lighting was probably not very good though, and keeping the fire going would have been a chore.

Winter was a time for stealing ponies and I can’t imagine that. You’d be walking, possibly hundreds of miles, traveling light because everything you brought you had to carry. Gore-Tex didn’t exist, and I don’t care how much bear grease you put on your moccasins your feet are going to be wet and cold. No goose down parkas. A buffalo hide is warm but it’s also heavy—would you bring one on your raid? I read the story of a Crow warrior once whose name, “Two Leggings,” was a corrupted translation of the teasing nickname given by his friends, who called him “Many Leggings” because of his propensity to bundle up when it got really cold out. But even he was astounded by the amount of clothing the white guys wore, and their aversion to facing winter weather, even when it involved something as important as recovering one’s own stolen ponies. My friend the Sarge thinks people of yore were genetically superior—I won’t go that far but I do think they acclimatized much better than us modern humans can imagine. Pain and suffering were part and parcel of daily life, at least in the winter.

The idea of a simple life in a tipi is a romantic one. The reality is somewhat different, I suspect. Even John Colter and John Johnston moved back to civilization.

Written By

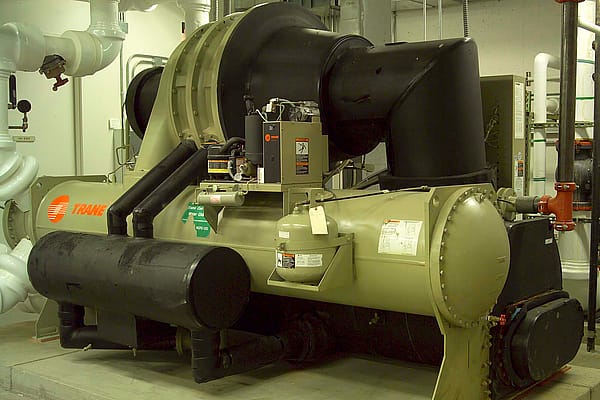

Phil Anthony

Phil Anthony is the Operating Engineer at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. He has been in the HVAC-R service industry for over 30 years (fifteen of them at the Center.) Phil holds journeyman certificates through the City and County of Denver as a steamfitter and a refrigeration technician, and a low-voltage electrical technician’s license with the state of Wyoming. An artist, poet, musician (sort of,) and avid outdoorsman, Phil has been called "a true renaissance man."