Frontier Violence Would not Prevail – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2001

Frontier Violence Would Not Prevail

By Mark Bagne, Guest Author

Driving down main street of almost any western town, you’ll see the manicured lawns of neatly kept homes, the downtown business section busy with shoppers, the combination police station and jail, the fire hall, city hall, and clock tower of the courthouse rising from a town square. You may notice a police officer cruising main street or a lawyer carting his briefcase through the courthouse door. So common have these symbols of law and order become that you barely give them a second thought as you continue on your drive through town.

For a legal historian like John W. Davis, the sight of the police station or courthouse at the heart of any western town provides reason to reflect on how far the West has come. It’s hard to take the forces of law and order for granted when you understand the struggle they endured to survive and finally prevail over forces of violence that ruled the frontier.

Davis was one of four specialists in western law and the history of law enforcement who asked participants in the Frontier Justice Symposium one October morning to remember the days when the county sheriff or federal marshal was the underdog pitted against the sharp-eyed outlaw who was more apt to fire a bullet in his back than face him down in a stiff-legged shootout at High Noon.

During the “Westering of America,” a phrase penned by Steinbeck, the establishment of law was among the last elements of civilization to set down roots on the open spaces being prodded by explorers, trappers, and traders. As settlers sketched out territories and carved boundaries of states, federal lawmen and local officers worked within confusing jurisdictions—sometimes chasing the same criminal for different crimes, according to Frederick “Ted” Calhoun, a former historian for the U.S. Marshal’s Service.

Unclear about the scope of their mission, lawmen heading West for their first assignment were entering a dangerous world. An officer charged with enforcing court orders in the 75,000 square miles of Indian Territory after the Civil War confronted what was “probably the wildest place in western history, or on the face of the globe,” according to Robert B. Smith of the University of Oklahoma College of Law.

At the peak of its lawless period, other pockets of the West such as the Big Horn Basin of Wyoming were also rocked by the “violence and mayhem” of the times. It was a world dominated by rough-and-tumble cowboys whose idea of a little fun was to circle round a grizzly bear and try to lasso the beast, a scene captured in the Charles M. Russell painting The Stranglers.

In this vacuum of law and order, Davis points out, angry citizens were known to resort to vigilante justice – like the mob of cowboy raiders who swooped out of the darkness one night, blasting their guns, killing three sheep herders and leaving their wagons ablaze in the aftermath of the Spring Creek Raid.

Smith recalls another form of vigilante justice resulting from an ill-conceived effort by the Dalton Brothers to pull off “one last strike” on two banks in the small town of Coffeyville, Kansas. In the wake of that 1892 episode, the entire town rallied to defeat the bank robbers and parade their slain figures down main street. Newspaper photographers propped the dead outlaws up against a fence to pose a photo capturing the moment.

According to another story of the times, Smith told symposium observers, Judge Parker, “The Hanging Judge,” once hung six convicts at the same time on one gallows. His gallows could handle as many as 12 and was purported to be the biggest in the world outside of France. His assistant, the “Prince of Hangmen,” kept the gallows in perfect condition, and his well-oiled ropes in a special basket.

Stories like those represent the extremes of the times, not the daily course of life, but symposium speakers used them to help set the stage for the climate of danger and confusion facing law officers on the frontier. The times demanded a well-trained force of professional lawmen, but the marshals who took up the challenge rarely fit the Matt Dillon mode.

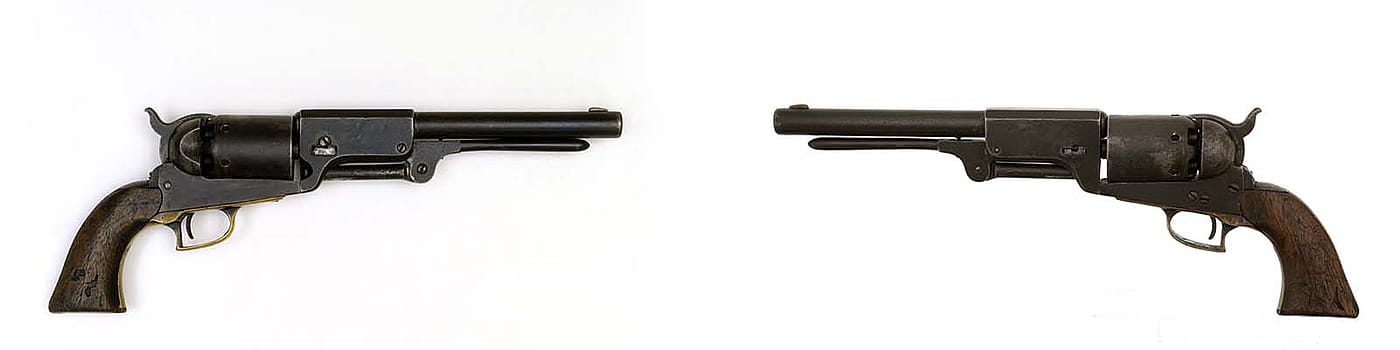

Drafted into the frontier version of a war against crime, marshals heading out on their mission were provided few instructions, little training and a considerable dose of harping from government officials to keep their expenses down. “These were courageous and brave men, but they were amateurs,” Calhoun says. “They were not professional gunfighters like the outlaws they chased who lived and died by their guns.”

The outlaw of the West presented a formidable enemy. He was a wily character who was not about to challenge the sheriff to a clean and surgical duel on main street like the High Noon shootout staged in western movies. “The real pro shootist didn’t fight like that,” Smith points out. “He’d shoot you in the back if at all possible, and he’d shoot you in the dark if he could.”

The “amateur” federal marshals who served on the frontier in the late 1800s were often no match for the superior forces of outlaws and vigilante mobs. That imbalance of power spelled disaster for the lawmen that lost their lives in the Going Snake Massacre in Indian Territory in 1872, Calhoun says.

An American Indian man killed his wife. He was charged with murder under Indian law and was ordered to stand trial in Indian Court. Since there was no courthouse in the vicinity, authorities established a makeshift court in a schoolhouse. As judges and attorneys gathered for the trial, a platoon of federal marshals took up posts around the schoolhouse to guard against potential violence from angry citizens. While the marshals stood guard, a ten-member posse of vigilantes, including four relatives of the murdered woman, drew up battle plans for an attack.

The posse of vigilantes swarmed down on the schoolhouse and overwhelmed its defenders. Even the judge and the prosecutors took up arms to aid in the defense of their courtroom, but the vigilantes slaughtered the marshals in the field outside. They shot seven marshals dead and inflicted fatal wounds on another.

Movies often show the sheriff racing out of his office and leaping on his horse in pursuit of the outlaw galloping away from the scene of the crime. In reality, several days often passed before a sheriff was alerted to a distant robbery or murder. By the time he reached the crime scene, the criminal was long gone. “A sheriff did not actually do a lot of policing,” Lauer notes. “For the most part, being a sheriff was a pretty dull pastime.”

Speakers at the forum suggested law enforcement was hamstrung during its early years on the frontier because it had stretched too far beyond its critical support network of civilization. Without the sources of funding, communication, an established court system and other efficiencies of settled populations, law officers had to wait for civilization to reach them.

Davis points to a day in 1909 when a jury comprised mostly of farmers “finally vanquished” the rule of vigilante justice in the Big Horn Basin. In the wake of the Spring Creek Raid that left three sheepherders dead, the cattlemen suspected of murder were brought to trial. This was a time when cattlemen ruled the region and held the forces of law in disdain. To this point in Wyoming history, no cattleman had ever been convicted of a crime.

“But the pace of change was moving faster than anybody knew,” Davis points out. “When the trial started and the jury was seated, the jurors were a group of neutrals. The basin had changed as irrigation brought farmers to the land.” As the jury returned a first-degree-murder conviction against defendant Herb Brink, “the forces of law and order took control and the rule of vigilante justice was finally vanquished.”

Post 044

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.