The Art in the Stone: Turquoise

This article was written by guest author Gene Waddell for the exhibition Adornment in the West: The American Indian as Artist. Gene is owner of Waddell Trading Company of Scottsdale, Arizona, a family owned business specializing in Indian jewelry and arts.

Turquoise in scientific terms: Turquoise forms in highly faulted and fractured zones of igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rock. It forms in arid regions and at elevations of 3500 to 8500 feet. Turquoise forms in a precipitate (chemical reaction) with copper and aluminum phosphate. Its color ranges from various shades of blues and greens. If more iron is present, the turquoise will be greener.

The history of the turquoise stone being used in jewelry dates back 10,000 years from many locations in the Middle East, including the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt and Persia. Turquoise was worn not only for its beauty but also for its mystical powers. It was believed to heal, ward off danger, and bring good luck as well as have spiritual connections to the spirits.

The Indians of the southwest began using turquoise in jewelry over 2,000 years ago in the Four Corners area which is now Colorado, Utah, Arizona and New Mexico.

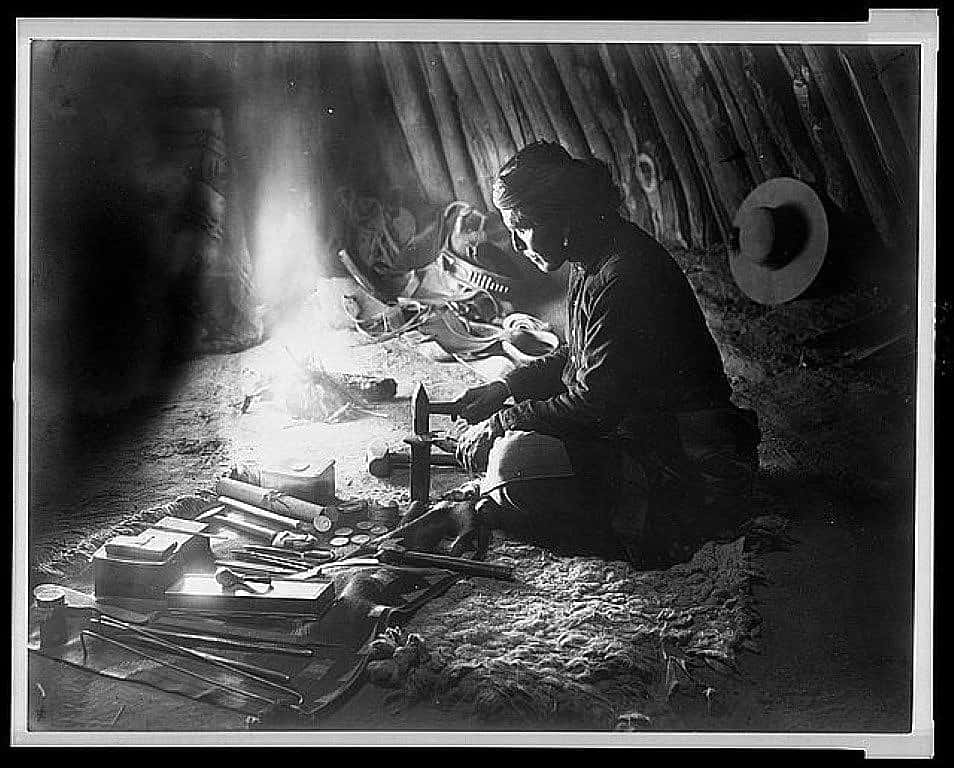

The jewelry made during this time was fashioned into pendants, drilled as beads, and mosaic inlaid on shells. It wasn’t until the 1870’s, after the “Long Walk” of the Navajo to Bosque Redondo* that the Navajo began to do silverwork. During that time they learned how to make jewelry from the Spanish blacksmiths which became an essential part of the Navajo economy. This was the beginning of “Jewelry as Adornment” for the Native Americans of the Southwest using turquoise and silver. The Zuni and Hopi followed suit in the making of turquoise jewelry using their own cultural styles. From 1910 to 1920 jewelry was more primitive and crude and it was the beginning of an ethnic jewelry deeply rooted in the cultures of each tribe.

Most of the silversmiths seemed to be born with an innate talent of making jewelry as an art form. It was during the time from 1870 to 1930, the Indians began making beautiful rings, pendants, necklaces, squash blossoms, bolos and concho belts. In the 1950’s and 60’s, as better tools and machines were developed, this jewelry became even more refined. From the 1970’s to today we have the contemporary Indian jewelry movement. Cross cultural styles of design are seen. Navajo and Hopis are doing inlay with a different twist, not like their Zuni counterparts.

There have been many turquoise deposits mined in the American Southwest over the last 75 to 80 years. Large operations in Arizona were primarily massive open pit copper mines in which turquoise was a by-product. These mines produced the most turquoise over the years because of the large amount of money and equipment available. The smaller turquoise operations in Nevada, New Mexico and Colorado, produced much less turquoise in comparison.

Classic southwest turquoise mines are the ones with the most highly priced and desired turquoise. This turquoise is desired by the silversmiths, the public, the store or Gallery owners and especially the collectors.

A partial list of the finest and most desirable mines is as follows:

| Nevada | Arizona | New Mexico | Colorado |

| Lander Blue | Bisbee | Cerrillos | Cripple Creek |

| Lone Mountain | Morenci | Tyrone | Kings Manassa |

| #8 | Kingman | Hachita | Villa Grove |

| Red Mountain | Sleeping Beauty | ||

| Blue Gem | Castle Dome | ||

| Godber | Turquoise Mountain | ||

| Nevada Blue | |||

| Indian Mountain | |||

| Carico Lake | |||

| Fox | |||

| Royston | |||

| Blue Diamond |

Of these mines, only 6 are still producing turquoise today. There are a few lesser known mines that produce small amounts of turquoise. The ones mentioned above are the “Classics.”

* “The Long Walk” refers to the January 1864 forced relocation of approximately 8,500 Navajo from their homes in Arizona to the Bosque Rendondo Reservation, over 300 miles away, in Eastern New Mexico.

The exhibition Adornment in the West: The American Indian as Artist ran June 19 – October 16, 2015.

Written By

Rebecca West

Named as the Center of the West's new Executive Director in April 2021, Rebecca West has served as Curator of Plains Indian Cultures, as well as the Collier-Read Director of Curatorial, Education, and Museum Services. Rebecca has worked with the people, objects, ideas, and programs that define the Plains Indian Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.