Mark Twain and Buffalo Bill Cody, part 3 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Fall 2006

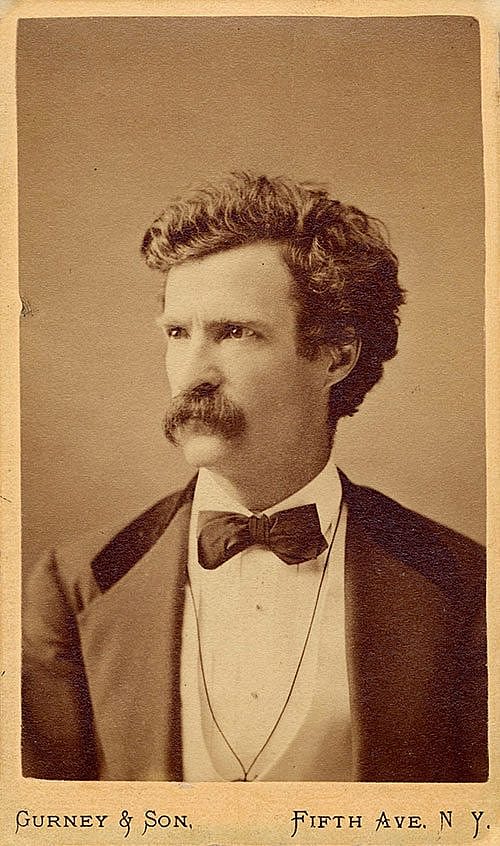

Mark Twain and Buffalo Bill Cody: Mirrored through a Glass Darkly, part 3

By Sandra K. Sagala

Guest Author

In this, the third in a four-part series, Sandra Sagala compares the fame of two of the American West’s best-known personalities—Mark Twain and Buffalo Bill Cody—as they made their marks on nineteenth-and-twentieth century America.

If you missed the start of the series, click here to go to part 1.

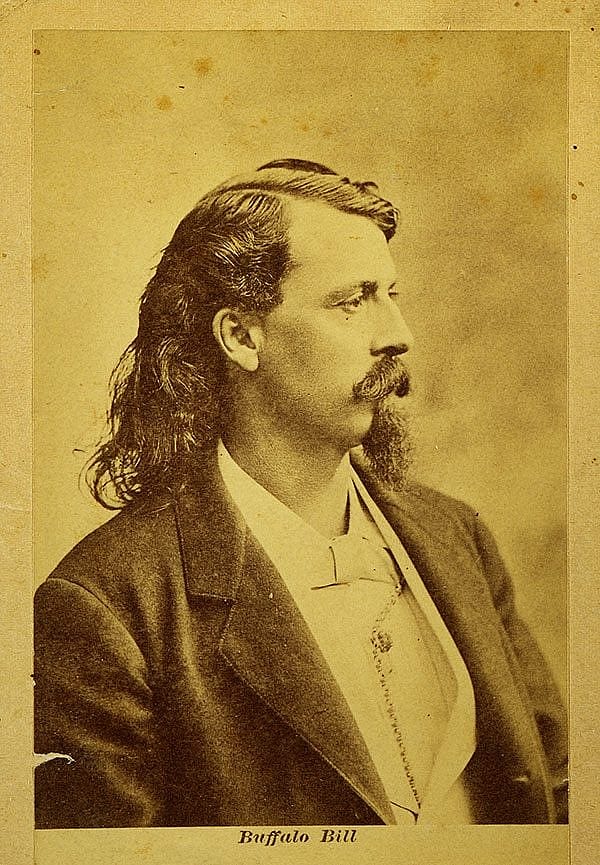

In the nineteenth century, while many of Cody’s and Clemens’ contemporaries never moved farther than 50 miles beyond their birthplaces, some crossed the country in search of better land, higher wages, or simple adventure. Unlike most of them, Cody and Twain became world travelers. Cody toured the country from east coast to west with his stage plays and Wild West for 15 years. Then he took his show to Europe, for four years at a time. While in England, he held a special command performance for Queen Victoria who was delighted with the exhibition. During one performance, Buffalo Bill drove four European kings—those of Belgium, Denmark, Greece, and Saxony—around the outdoor arena in his Deadwood Stagecoach. In Italy, he presented the Wild West to Pope Leo XIII on the anniversary of the pontiff’s ascension to the throne of St. Peter. Cody—for all his homespun, plainsman past—grew comfortable entertaining royalty and world leaders.

Mark Twain traveled even more widely than Buffalo Bill. Sought after as a speaker, he addressed audiences not only across America, but also in Europe where he lived for years at a time. His lecture circuit encompassed the globe, taking him to the Sandwich Islands, India, the Holy Land, Ceylon, Russia, and Australia. Clemens, too, was comfortable with high-ranking, influential people. He was just a fellow writer to his friends—future notables whom twenty-first century readers regard nearly as popular as he—such as Bret Harte, Charles Dickens, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Helen Keller. Twain twice met King Edward VII, successor to Queen Victoria, first in Germany, and again at a Windsor garden party. He grew close to former president Ulysses S. Grant during the last year of Grant’s life when a publishing company Twain originated acquired the contract to publish Grant’s Civil War memoirs. Twain involved himself in promoting Grant’s book. With that success, he secured sanctions for a biography of Pope Leo XIII, a venture which, though profitable, fell far short of expected earnings.

As confident as they were in performing before large international audiences, both men began their careers as frightened as anyone might be, faced with an expectant crowd. “Before I well knew what I was about, I was in the middle of the stage, staring at a sea of faces, bewildered by the fierce glare of the lights, and quaking in every limb with a terror that seemed like to take my life away,” Twain admitted. Buffalo Bill Cody, at his theatrical debut in Chicago in December 1872, watched the crowd enter the opera house through holes in the curtain as his “nervousness increased to an uncomfortable degree.” When the curtain rose, fellow actor Ned Buntline “appeared, and gave me the ‘cue’ to speak ‘my little piece,’ but for the life of me I could not remember a single word.” In the wings, the manager attempted to prompt him, “but it did no good; for while I was on the stage I ‘chipped in’ anything I thought of.” Finally, with Buntline’s coaching, Cody managed to relate a hunting story the audience greeted with foot stampings and hoots of pleasure.

While he did overcome the stage fright and develop his own “voice,” Twain often resorted to what one expert calls his “system of destruction.” His method of humor was to present reality, by “unwriting” what others had done. For instance, in his travel guide Innocents Abroad, Twain wrote about the myriad shrines he visited in Italy: “Some of the pictures of the Saviour were curiosities in their way.” He went on to describe the hammer, nails, sponge, reed, and crown of thorns affixed near a crucifix as accoutrements. Instead of inspiring faith as a travel writer might expect from such a display, Twain found “the effect is as grotesque as it is incongruous.” He also loved to entertain by insisting he was telling the truth. In Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Twain, using Huck’s voice, writes, “You don’t know about me without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer; but that ain’t no matter. That book was made by Mr. Mark Twain, and he told the truth, mainly. There was things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth.” Not that Twain was above prevarication. He quoted Thomas Carlyle who said, “A lie cannot live forever,” but Twain added in his dry fashion, “It shows that he did not know how to tell them.”

Buffalo Bill Cody worked to present history as he saw it, real and imagined, but placed himself at the center. In his Wild West shows, Cody featured representations of pioneers’ travails with the Indians. Instead of demonstrating the cruel reality of the scalpings and tortures—hardly entertainment—he happily-ever-aftered the stories. Cody charged into the arena in the nick of time to save the settlers from sure destruction. His depiction of Custer’s Last Stand always ended with him galloping up after the last soldier had fallen. His crew unfurled a large sign proclaiming “TOO LATE,” insinuating Cody had tried to save the hapless general, when, in fact, Cody was hundreds of miles away from Little Big Horn when Custer and the Seventh Cavalry met its fate.

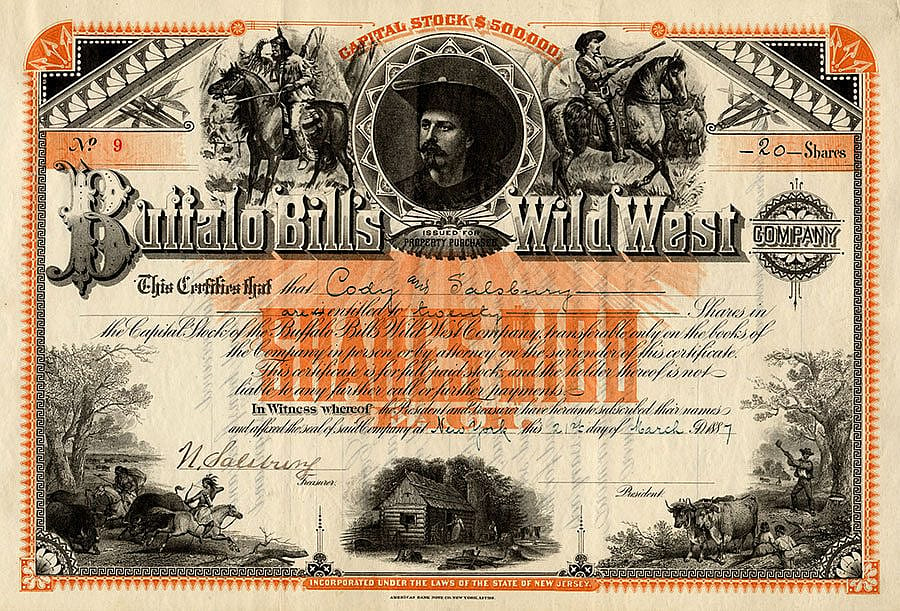

Between 1876 and 1886, Twain and Cody enjoyed very productive years. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885) made Twain a household name. With his newly earned wealth, he purchased a large house in Hartford, Connecticut. Since 1869, Elisha Bliss of the American Publishing Company had promoted many of Twain’s works but when Twain became unhappy with Bliss over the publisher’s increasingly non-Twain book list, Twain started his own subscription book company and set up Charles L. Webster to run it. Within two years the publishing firm found success with Grant’s Memoirs.

Dime novel writers, in particular Ned Buntline, whom Clemens may have met in May 1868 on a Sacramento River steamboat, discovered Buffalo Bill Cody and aggrandized his heroic adventures in the yellow-paged paperbacks. Borrowing from his own literature, Buntline created Cody’s first drama and cast himself in a major role. By 1879, after seven profitable seasons as a dramatic actor in frontier dramas, Buffalo Bill was persuaded to write his autobiography. When he finished it, Elisha Bliss’s son, Frank, also of the American Publishing Company, published it, making it perhaps one of the first books sold by subscription, that is, through book agents going door-to-door. Cody was a natural born storyteller. During the times he was hired to guide eastern sportsmen on hunting trips west, he entertained his charges with tall tales around the campfire. In his early years as an actor when he forgot his lines, he adlibbed stories around the fake campfire onstage.

Mark Twain earned his acclaim through his public lectures and writings, many based on his boyhood or his travels. In The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Tom says in the introduction, “most of the adventures in this book really occurred; one or two were experiences of my own, the rest those of boys who were schoolmates of mine,” while in The Mysterious Stranger, the narrator is a printer’s apprentice, as was young Twain. Twain’s travel experiences inspired Innocents Abroad and Roughing It. During the years he wandered around the West, Clemens learned to tell stories from old mountaineers and miners. While on long steamboat tours on the Mississippi, storytelling helped pass the time. But writing his own story came difficult to him, even though much of his fictional writing is clearly autobiographical. Clemens began his “official” story in 1870, and then put it aside, working on it intermittently over the next 30 years. Becoming more serious about it after the turn of the century, he found he enjoyed the process more of adding to it by dictating to his secretaries and by talking to A.B. Paine, his biographer.

Whether or not the other man read his contemporary’s biography, Mark Twain was certainly informed about Buffalo Bill, having attended Cody’s Wild West show more than once as his letter indicates. In his 1892 book American Claimant, Twain’s character Lord Berkeley dons a hat “of a new breed to him, Buffalo Bill not having been to England yet,” though in reality, Cody had traveled to England since 1887. In his 1905 novella “A Horse’s Tale,” Twain used Soldier Boy, supposedly Buffalo Bill’s favorite horse, as narrator. In the fiction, after the horse saves a general’s daughter from wolves, Buffalo Bill generously offers the animal to her as a gift.

Between his early theatrical seasons, Cody returned to the frontier. Playwrights chronicled his summer’s adventures in plays that he performed the following season. One of his plays was based on the Mountain Meadow Massacre, scene of an alleged Mormon attack against an emigrant wagon train in 1857 Utah. Sam Clemens had visited the scene in 1861 and summarized the contradictory explanations heard around the territory in chapter 17 of Roughing It. The carnage was possibly “the work of the Indians entirely,” or “the Indians were to blame, partly, and partly the Mormons” or “the Mormons were almost if not wholly and completely responsible for that most treacherous and pitiless butchery.” Ultimately, it was the Paiute Indians along with Danites, the Mormon guerrillas, who were to blame for the slaughter. Mormon leader John D. Lee was hanged on the spot 20 years later, an event that was featured in Cody’s drama.

Continued in Part 4...

About the author

Sandra K. Sagala has written Buffalo Bill, Actor: A Chronicle of Cody’s Theatrical Career and has co-authored Alias Smith and Jones: The Story of Two Pretty Good Bad Men (Bear Manor Media 2005). She did much of her research about Buffalo Bill through a Garlow Fellowship at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming. She lives in Erie, Pennsylvania, and works at the Erie County Public Library.

Post 151

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.