Art and Exploration of the American West: The Legacy of John Mix Stanley

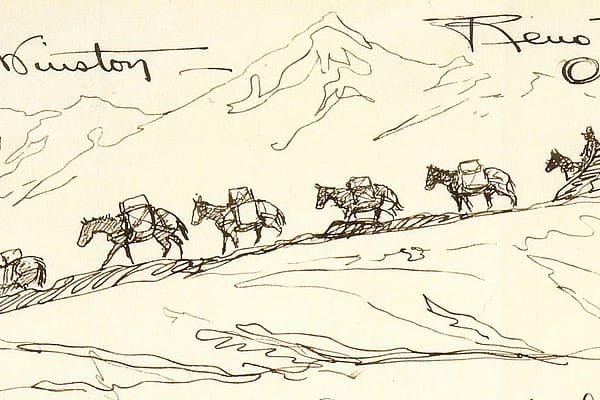

In 1853, the United States Government organized surveys to ascertain the most practical route for a transcontinental railroad. American explorer-artist John Mix Stanley (1814–1872) was enlisted as an artist for Isaac I. Stevens’s Northern Survey. This expedition granted Stanley the opportunity to record landscapes and Indian cultures on his journey across the country.

Stanley first traveled west more than a decade before the Stevens survey, in 1842, and became a premier painter of the western scene and American Indians during his lifetime. He died in 1872, only seven years after a devastating fire at the Smithsonian Institute destroyed the majority of his life’s work then on display. The Center of the West debuted the first major study of art of John Mix Stanley in 2015, and has in its collections sixteen works by the artist.

Currently on view in the Whitney Western Art Museum are eight lithographs (prints) produced after Stanley’s original artwork. These lithographs were inspired by Stanley’s journey with Stevens and range in topic from river and mountain landscapes to fortified structures and buildings.

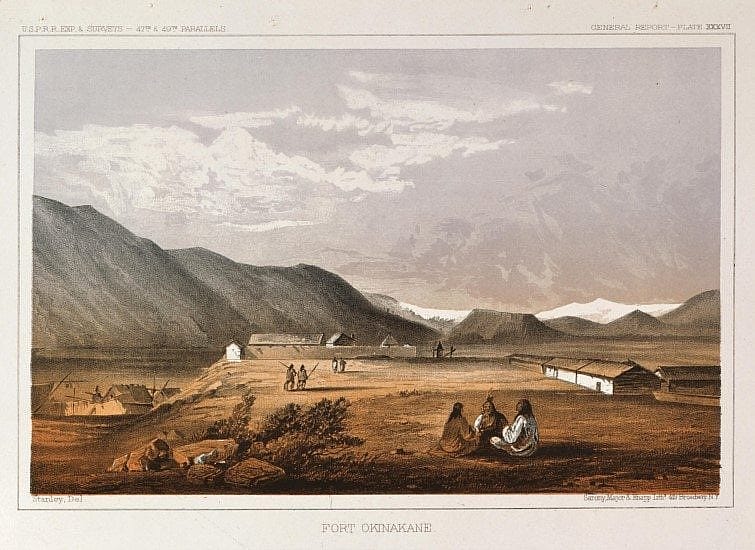

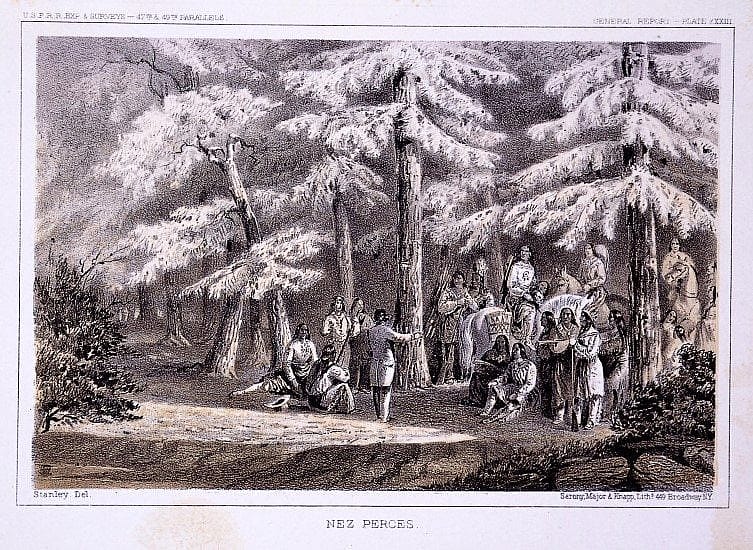

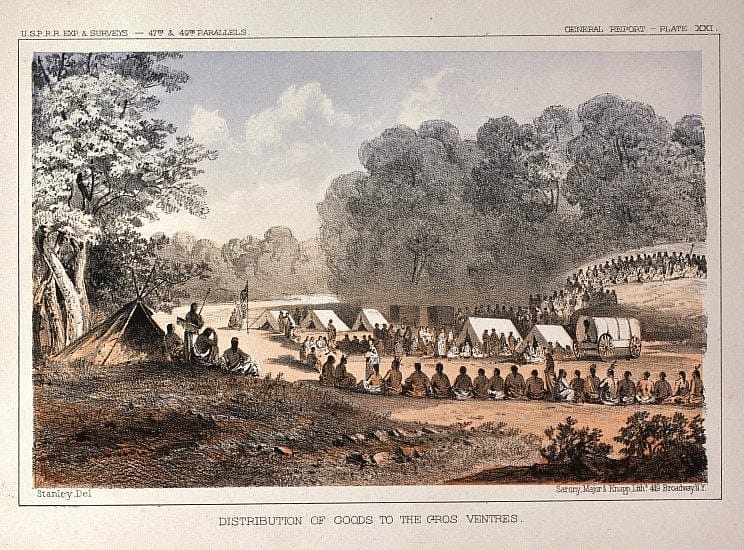

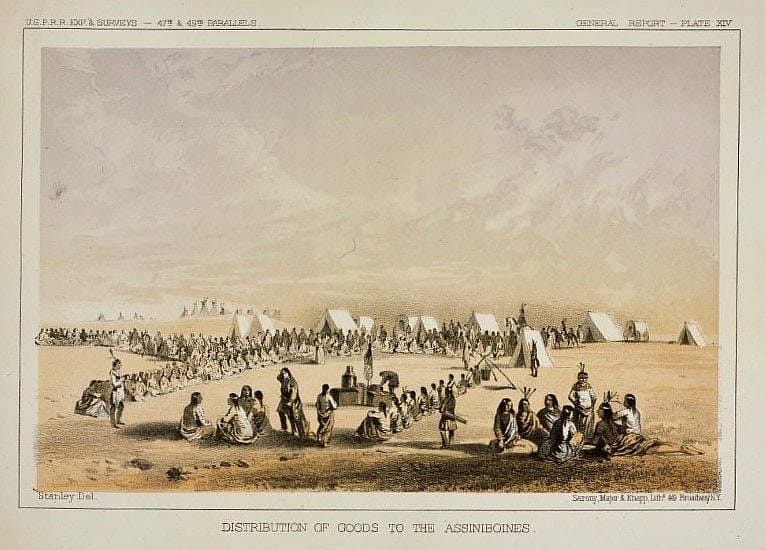

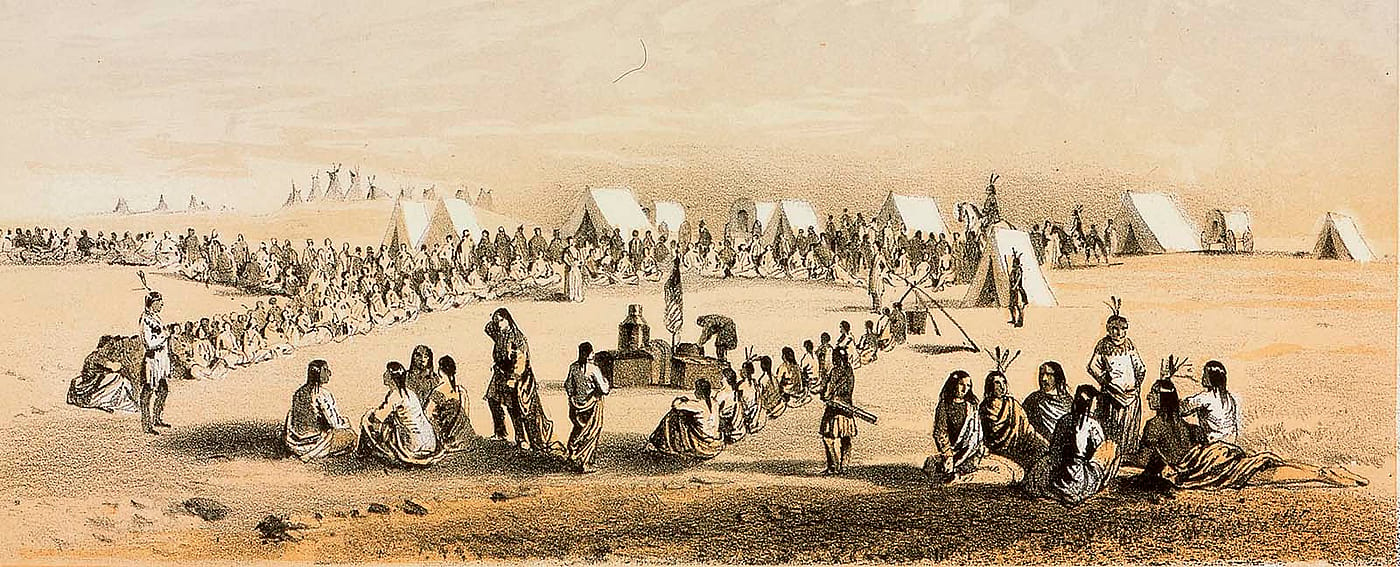

My favorite lithographs on display include Nez Perce, the Distribution of Goods series, and Fort Okinakane. These four prints provide glimpses into Native American cultures and lifestyles during the mid-nineteenth century, as seen through Stanley’s eyes. Several depict American Indians’ clothes and dwellings, and others picture interactions between Native Americans and Euro-Americans.

Stanley rendered the American Indians in Nez Perce as cautiously friendly toward a Euro-American male who stands with his back toward the viewer, arm outstretched in conversation with his audience. Wearing a tailored coat with tails and a waved hairstyle, the Euro-American male is the only figure with his back fully toward the viewer. He stands at “center stage,” in a clearing just beyond the edge of the forest. The American Indian audience members sit on the ground or astride horses or stand in groups among the trees.

The Distribution of Goods series and Fort Okinakane further showcase the artist’s interpretation of interactions among American Indians and Euro-Americans. In these scenes, Stanley depicts the progressive adoption of Euro-American lifestyles by American Indians.

Although Stanley created the imagery for these lithographs in promotion of the railroad’s westward expansion, he also captured in them depictions of cultural interaction and exchange during a tumultuous time in our country’s history.

Stop by the Center and enjoy the selection of Stanley works before they return to the vault!

Bibliography:

Augherton, Tom. “Buckeye Gets Burned.” True West Magazine. Last modified September 17, 2015. http://www.truewestmagazine.com/buckeye-gets-burned.

_____. “John Mix Stanley.” Smithsonian American Art Museum Renwick Gallery. Accessed October 10, 2016. https://americanart.si.edu/artist/john-mix-stanley-4600.

Pipes, Nellie B. “John Mix Stanley, Indian Painter.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 33, no. 3 (September 1932): 250-258.

Written By

Nicole Todd

Nicole Todd was formerly the Curatorial Assistant for the Whitney Western Art Museum. She graduated from the University of Oklahoma, with bachelor’s degrees in Zoology and Art History, and a master’s degree in Art History, with a focus on western American art and a specialization in Will James’s art. As Curatorial Assistant, Nicole engaged in art historical research, supported educational programming, answered public inquiries, and contributed to the Whitney’s online presence.