Harry Jackson’s Sacajawea – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2006

Harry Jackson’s Sacajawea

By Marguerite House

Media Coordinator/Editor, Points West

Literally every day, I pass Harry Jackson’s monumental sculpture Sacajawea as it stands proudly in the Cashman Greever Gardens of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Until my interview with the artist, little did I know Harry originally intended for it to serve as one of Wyoming’s representative sculptures in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, D.C. When I asked Harry why the plan had gone awry, he responded, “Politics.”

In the fall of 1975, John Barber of the Pine Bar Ranch near Lander, Wyoming, approached Harry about doing a monumental sculpture of Lewis and Clark’s Indian guide Sacajawea to be placed in the U.S. Capitol, along with Wyoming’s other representative sculpture of Esther Hobart Morris. “When I asked who was going to pay for it,” Harry said, “John told me, ‘Don’t worry about that; just leave it to me.'”

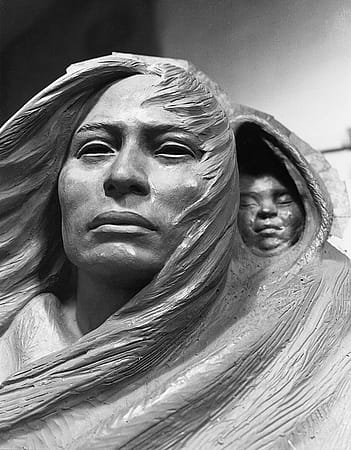

To find a model, Harry contacted his friend Reverend Patterson Keller in Cody, Wyoming, who asked a chaplain on Wyoming’s Wind River Indian Reservation to find a young Shoshone woman, preferably with a small child, to serve as the model for Sacajawea. Ultimately, it was Marie Henan Varilek who would pose for hours in Harry’s Lost Cabin, Wyoming, studio. Harry was quite satisfied with his first studies, noting, “They embody the monumental quality and majesty befitting a statue to stand 10 feet high in the U.S. Capitol, as well as our Wyoming State Capitol.”

Yes, negotiations had broadened the original Cheyenne commission to include not only the U.S. Capitol, but the Wyoming State Capitol as well. However, repeated controversy over Sacajawea’s actual burial site—indeed whether she’d been in Wyoming at all—left many wondering about her suitability as a subject truly representing Wyoming. In the end, the commission established a competition to choose a sculpture. Not only did Harry enter the competition in 1977, he caused another academic fray by spelling the Indian guide’s name with a “j” as the Shoshone Tribal Chairman asked him to do, rather than the “g” that Lewis and Clark had used.

Harry began working on studies for the sculpture only to have the deal fall through in March of 1978 as another sculptor’s work was eventually chosen by the commission. Nevertheless, according to Harry, his work had reached new levels with his efforts to create Sacajawea. “My desire to master volume and mass in painting on a flat surface naturally brought me to paint colors directly on to the actual three-dimensional surfaces of my heroic Sacajawea bronze. Sculpture for me is a way to be a better painter.”

The project languished a mere four months when Helen and Richard Cashman of Minneapolis “came to the rescue,” as Harry puts it, and generously donated the funds to cast Sacajawea as an outdoor sculpture in conjunction with the newly built Plains Indian Museum at the Center. The new commission was signed in August 1978, and in January 1979, Harry returned to his studio in Italy to “[go] to work immediately on the mass of water clay that had been roughed out on the huge armature.” By February 20, 1980, the final modeling of Sacajawea was complete. It would be cast in six sections—and it would be painted.

“I can’t imagine the world without color,” Harry maintains. “Walking down an ordinary street or out in a plain piece of unbroken country, even on a gray day, I see everything like it was painted.” In their book Harry Jackson, 1981 (Harry N. Abrams, Inc., publisher), authors Larry Pointer and Donald Goddard wrote, “Once freed from the absolute demands of realism and historical accuracy, he [Harry] was able to project the total image as both sculpture and painting, rather than just painted sculpture…. He was now painting on the massive forms as though they were a three-dimensional field or canvas.”

Sacajawea was unveiled and dedicated at the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] on July 4, 1980, a completed monumental sculpture, but also a “seer-artist” liberation for her creator. As he finished telling me the story about this, his first monumental sculpture, and the abundant details of researching, creating, and crafting that accompanied it, Harry acknowledged the project was transformed into more than a commissioned work. For him, it became a personal endeavor as he depicted not only Sacajawea, the guide, but also personified pure motherhood. For you see, the more Harry sculpted, the more he connected with a relationship denied him when he was Sunny, a lifetime ago—that of an uncompromised mother.

Read more about Harry Jackson in this post.

Post 196

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.