Constructing and consuming atomic culture in the American West – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2007

Uranium mines to Atlas missiles: Constructing and consuming atomic culture in the American West

By Michael A. Amundson, PhD

Editor’s note: The West is synonymous with cowboys, pioneers, horses, cattle drives, Indians, trappers, and landscapes like no other. But in the 1890s, radium was discovered on the Colorado Plateau, beginning a new relationship between the West and radioactivity. From the World War II top-secret Manhattan Project to 1960s atomic testing in Nevada, images of new atomic pioneers, uranium mining cowboys and Indians, and mushroom clouds over magnificent landscapes helped usher in a new “Atomic West.”

Mike Amundson has made a career studying the American West; he received a 2007 Research Fellowship from the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West]. In that project, his focus was the historic western photography of Cheyenne, Wyoming, photographer Joseph E. Stimson. Here, we share an article borne out of his fascination with the “Atomic West.”

Introduction

Several years ago, I was invited to present a paper at the Eisenhower Presidential Library’s conference on 1950s atomic culture. As an American West scholar with a book on uranium mining and another on atomic pop culture, I was thrilled and readily accepted. But when the program arrived, I was a bit nervous to see that I had been sandwiched between presenters named “Kruschev” and “Eisenhower.” My anxiety deepened as I thought about what someone like me, not even alive in the 1950s, could say alongside former Soviet Premier Nikita Kruschev’s son Sergei, or President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s granddaughter Julie.

But as I thought more about my research—how everyday westerners had brought the atom into their lives—l realized I did have a story to tell, and that my own family history might help to understand the Nuclear West.

My father, Arlen, graduated from a small South Dakota high school in 1956 and then entered the Air Force where he studied electronics. Following a brief stint in San Antonio, Texas, he moved to Lowry Field in Denver, where he soon met the daughter of a Wyoming coal miner attending Colorado Women’s College. He served his four years; they married; and my father began working at the Martin Marietta plant in Denver. He was employed there about two years before moving north to Loveland, Colorado, where he began a long career with Hewlett Packard.

Even the cribbage games I played with my sister as we grew up in Colorado had a curious twist related to this time and place. The old board’s original pegs had been replaced with little metal pins—objects I later learned my father had scavenged from the Martin Marietta assembly line: tiny parts of a Titan I Intercontinental Ballistic Missile!

Just as the Kruschevs and the Eisenhowers were making some of the toughest decisions of the 1950s, ordinary Americans like my father became part of the growing nuclear landscape and culture of the American West. From mine to missile, the United States vertically integrated the nuclear production line, drawing workers into occupations such as uranium mining, missile construction, and plutonium manufacturing because they offered good wages and new opportunities.

“A” is for affluence…and the atomic bomb

At the same time, post-war popular culture hit on the atomic theme as a sexy way to sell the country’s growing affluence. Pop music, comic books, motion pictures, View-Masters, board games, defense films, and even business names joined in the nuclear frenzy resonating with the public on multiple levels. On one level, they reflected the continuing American interest in technology and science. On another, they echoed Eisenhower-era optimism and nuclear energy’s tremendous potential. On still another level, these expressions were simply diversions, part of the country’s developing disassociation with the devastating potential of nuclear warfare.

As a western historian, my focus is on the trans-Mississippi Nuclear West and the two ideas of “construction” and “consumption.” Americans first constructed nuclear landscapes across the region—from uranium mines in Colorado to Atlas Missile silos in Montana—under the premise of compartmentalization (i.e. separating resources for the sake of security). But there was another reason—a western, grassroots means to an old end: continued economic prosperity. Then, westerners joined the American public at large in consuming atomic popular culture, popularizing it, and making this powerful weapon seemingly benign.

Radium, uranium, plutonium

The West’s affair with nuclearism goes back more than one hundred years to the Colorado Plateau’s radium mines. First discovered in the 1890s, radium was processed and sold as a cancer cure through World War I. Uranium followed, with its primary purpose to serve as a paint pigment. World War II’s Manhattan Project, the mission to develop the first nuclear weapon, truly ushered in the region’s Nuclear Age. It utilized federal lands, attractive to the project’s leaders because of the sparse but patriotic and politically weak populations, and the region’s wide-open spaces.

The nuclear industry procured top-secret sites to mine and mill uranium in Colorado; produce plutonium at Hanford, Washington; construct atomic bombs at Los Alamos, New Mexico; detonate one at nearby Trinity in 1945; and train its delivery crew over the salt flats of Nevada and Utah. By the time its work was known at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the West was the nucleus of America’s atomic world.

With the conclusion of the war and the failure to either end nuclear development or internationalize it, the U.S. entered the Cold War. It sought to expand its nuclear facilities both for continued weapons growth and testing, and to begin the seemingly promising development of atomic energy for peaceful uses.

As with the Manhattan Project, political leaders in the new Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) sought to diversify the West’s nuclear landscape. The idea was that if attacked, we would not be caught holding all of our nuclear eggs in one basket. Under the guise of national security, westerners greedily welcomed nuclear projects for patriotic and economic reasons, and any self-respecting western congressman worked hard to acquire them for his state.

Putting the “boom” in atomic

The nuclear production line grew across the region after the war. Uranium mining and milling expanded from Colorado into Wyoming, New Mexico, Arizona, Washington, Idaho, and South Dakota. Research and development increased at Hanford and Los Alamos but also spread to the Sandia Labs at Albuquerque, New Mexico, Lawrence Livermore labs in California, Rocky Flats near Denver, and Pantex near Amarillo, Texas.

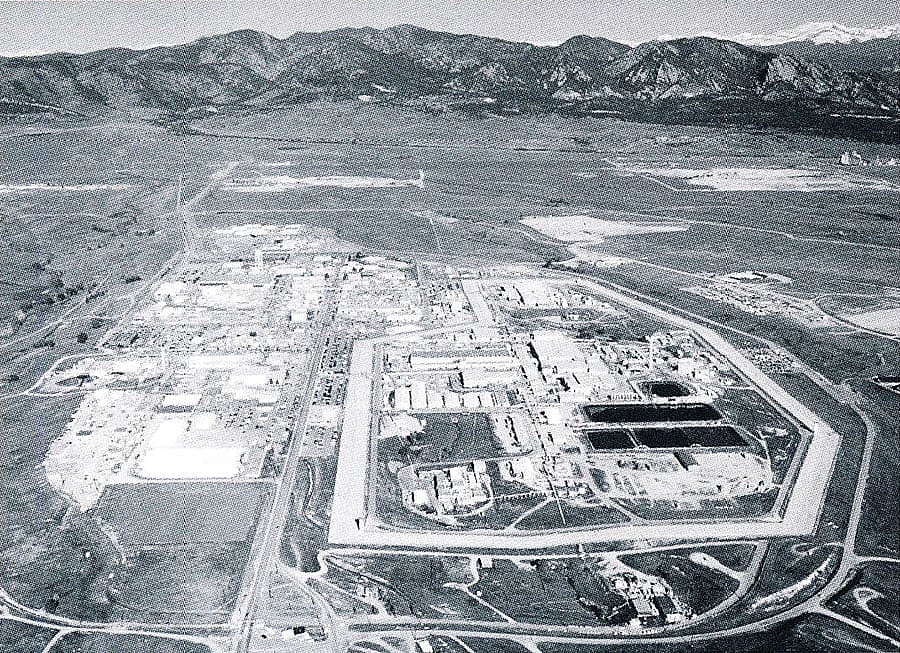

After conducting tests in the Pacific until the first Soviet bomb was tested in 1949, the government moved all bomb testing to a site northwest of Las Vegas, eventually detonating more than 150 bombs with fallout spreading across the Southwest. From there, scientists exploded bombs underground in Colorado, New Mexico, and Alaska as experimental engineering projects in Project Plowshare. At the Nuclear Reactor Testing Station near Idaho Falls, the AEC built forty test reactors to power both generating stations and the nuclear navy. Key civil defense air bases were also constructed: the Strategic Air Command in Omaha and the North American Air Defense Command just west of Colorado Springs.

As part of our national deterrent, Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) were sown across the West. First, Atlas missiles were constructed in San Diego and then planted with their crews in California, Nebraska, Wyoming, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas. After that, Titans—the same rocket that propelled our first astronauts into space, built in Denver by ordinary guys like my father—were placed in Colorado, California, Washington, Idaho, and South Dakota.

Titan IIs, bigger and more powerful, then found homes in Arizona, Kansas, California, and Arkansas. Finally, Minuteman missiles were deployed at Montana, South Dakota, Missouri, Wyoming, and North Dakota. By 1965, the year I was born, every state in the West—from Texas to Washington and from North Dakota to Arizona and Alaska—was part of our nuclear production, testing, and deployment line.

Unlike World War II’s classified Manhattan Project, these Cold War nuclear sites were not top-secret facilities thrust onto unknowing states. On the contrary, they were front page stories in local newspapers bragging about how boosters had secured part of the nuclear pie. A few examples: a headline in Grand Junction, Colorado, called local uranium miners “soldiers on the Cold War’s front lines”; the Denver Post welcomed Rocky Flats with the banner: “There’s Good News Today: U.S. to build $45 million A-Plant near Denver.” When word came to southeastern Idaho that the AEC was going to build its nuclear reactor testing station nearby, each past as well as the current president of the Idaho Falls Chamber of Commerce kicked in $100 (matched by the Chamber) to lure the project’s headquarters away from Pocatello, Idaho. The Tucson Daily Star showed construction photos of the local Titan II missile silos being built.

Ordinary, all-American boosterism

Ordinary westerners expanded this atomic boosterism through their everyday activities. In Las Vegas, postcards showed tourists lounging by pools watching distant mushroom clouds. An Atomic City boomed and busted in Idaho. Near Hanford, the Richland, Washington, high school football team was known as the Bombers and had mushroom clouds on their helmets. One could spend the night at the Atomic Motel in Moab, Utah; eat at Los Angeles’s Atomic Café; order a drink at the Atomic Liquors in Las Vegas; or eat a uranium burger (covered in tabasco) in Grants, New Mexico. Missile crews in South Dakota could get a 10-percent discount at the famous Wall Drug.

Atomic culture thus exploded into the American West through the dissemination of nuclear facilities and the grassroots boosterism it created. Local supporters patriotically added their locality to the nuclear landscape and welcomed the pork barrel federal jobs. These projects both increased national security by distributing the process across the region and developed a grassroots nuclear partisanship where locals defended the economic security of nuclear development and looked askance at doubters. Westerners wanted to continue the economic development started during World Warr II and to forever end their reputation as the “plundered province” of eastern capital. In doing so, they made “devil’s bargains” that the economic benefits of nuclearism would outweigh its effects.

Consuming the bomb

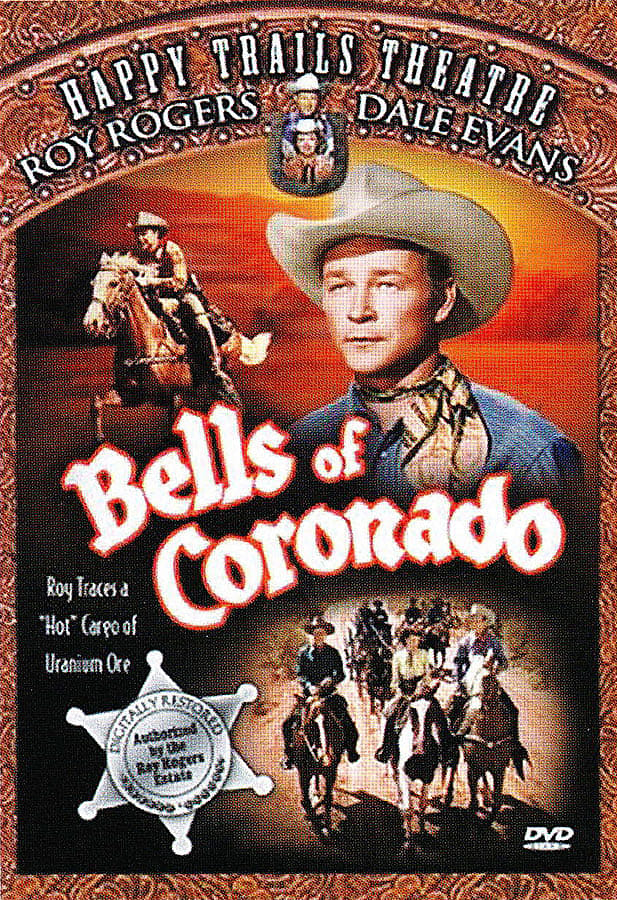

The construction of nuclear facilities provided a ready group of consumers for cold War atomic culture as marketers seized on all things atomic as the sexy new phenomenon that showed power and style. Comic book heroes like Spiderman and the Atomic Rabbit used the atom to fight evil. Films like Them! and The Atomic Kid sensationalized nuclear testing’s effects both melodramatically and humorously. The 1950 western Bells of Coronado even featured cowboy star Roy Rogers as an undercover insurance investigator following a mysterious murderer planning to sell American uranium to foreign spies.

Other forms of pop culture, including television shows, toys, board games, View-Master reels, cartoons, and even children’s literature, adopted similar schemes of atomic props used to support official government positions. Walt Disney’s classic children’s book Our Friend the Atom educated American youth from an obviously pro-nuclear viewpoint. Nuclear songs included “Atomic Baby,” “Atomic Boogie,” and “Atomic Love Polka.”

Bert the Turtle’s famous Duck and Cover cartoon taught children of the 1950s the basics of Civil Defense. Lesser known were the atomic beauty contests that incorporated a popular theme at the time: threats to world peace and domesticity could be assuaged by atomic weapons. At the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas, locals vied for the title of “Miss Atomic Bomb” clad in skimpy bathing suits covered with puffy white mushroom clouds—a contest promoters hoped would bring more tourists to the out-of-the-way desert locale to see the mushroom clouds up close and personal.

In Grand Junction, Colorado, uranium companies hosted a “Miss Atomic Energy” pageant where the winner received a truckload of uranium ore! Lucy and Desi hunted for uranium; Popeye had “Uranium on the Cranium”; and families played “Uranium Rush,” in which players touched a flashlight-like “Geiger counter” to the surface of an electric board in hopes of striking it rich.

Not so benign after all

By 1965, atomic culture had dispersed throughout the West with the construction of nuclear jobs and the consumption of atomic bombs as silly props for pop culture. Both means too often dissociated the devastating potential of nuclear warfare from the realities of everyday life.

It would take another generation and its actions—the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Test Ban Treaty, Vietnam, Watergate, Three Mile Island, and New Mexico’s Rio Puerco*—to get the West to examine critically its nuclear past. When it did, a whole series of problems showed the West’s true nuclear legacy: uranium miners with radon poisoning, down-winders exposed to fallout, and the Superfund environmental problems at Hanford and Rocky Flats.

The post Cold War American nostalgia for the 1950s Atomic World—witness the 1999 movie Blast form the Past or the cartoon The Simpsons—has been muddled by the real threats of 9/11. Beyond worrying about dirty bombs entering western ports, the region continues to deal with its nuclear past at Yucca Mountain, Nevada; Los Alamos, New Mexico; Moab, Utah’s uranium pile; and Rocky Flats. As the price of uranium skyrockets and the call for more nuclear power plants escalates, westerners again face a nuclear future while still coming to grips with its past.

Take heed

Take heed though. Historians and other social scientists are busily unraveling our complicated nuclear history to help Americans understand past lessons. As they expand the nuclear library, they are telling stories about the West’s nuclear history—stories of how uranium miners and their families came to be exposed to radioactivity, why the Miss Atomic Bomb pageant reflected 1950s Cold War domesticity, and how western icons like Roy Rogers adopted atomic themes into their films. There’s even one about the son of an ICBM assembly line worker who kept count of his cribbage hands with pegs from a Titan missile and later found himself at a Presidential library, quite at home talking among the offspring of world leaders.

*On July 16, 1979, one hundred million gallons of radioactive water containing uranium tailings breached from a tailing pond into the north arm of the Rio Puerco, near the small town of Church Rock, New Mexico. Even though few Americans were aware of it, some consider it the worst nuclear spill in U.S. history. Within three hours, radiation was detected as far away as Gallup, New Mexico, contaminating 250 acres of land and up to fifty miles of the Rio Puerco.

Dr. Michael Amundson is a professor of history at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff where he teaches courses on the American West, the Southwest, and recent American history.

Amundson is author of Wyoming Time and Again; Rephotographing the Scenes of J.E. Stimson and Yellowcake Towns: Uranium Mining Communities in the American West, as well as the co-editor of Atomic Culture: How We Learned to stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

Post 210

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.