A Public Monument: Theodore Roosevelt, “Rough Rider” – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2008

A Public Monument: Theodore Roosevelt, Rough Rider

By Stuart Gunn

Former Assistant Registrar, Whitney Western Art Museum’s 50th Anniversary

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs are gifts of A. Phimister Proctor Museum with special thanks to Sandy and Sally Church.

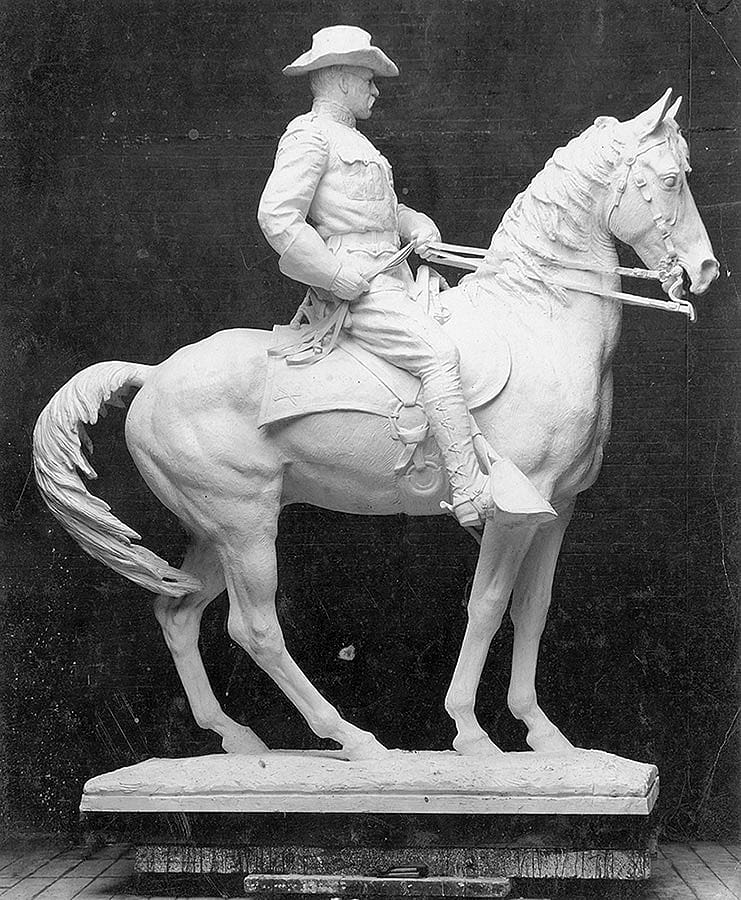

If public monuments must meet two requirements, that they be both beautiful and convey a message, then Alexander Phimister Proctor’s statue of Theodore Roosevelt met both criteria. Proctor’s contemporaries agreed that Rough Rider was indeed a work of art, and its dedication to the children of America served to transmit the values and ideals of the past to a future generation.

It was Dr. Henry Waldo Coe, a physician in Portland, Oregon, who was ultimately responsible for the creation of a monument to Theodore Roosevelt. The monument stands today on the South Park Blocks at Jefferson and Madison Streets, opposite the Portland Art Museum, formerly the site of the Ladd School, an Oregon public elementary school. Responding to the call of the City Beautiful movement, Coe came forward to offer a gift to the city of Portland in the form of a memorial to a personal friend and national hero, the late president (Roosevelt died in 1919), an offer that was gladly accepted by Portland city officials.

The project begins

Coe’s first task was to find a sculptor who was capable of creating a heroic-size bronze equestrian sculpture. In touring the studios of New York sculptors, he visited Proctor’s studio. Among the sculptor’s work, Coe saw the bas-relief of a mutual friend and was so impressed by the resemblance and Proctor’s ability to capture the character of the man, that Coe offered the commission to the sculptor on the spot. Proctor gladly accepted.

From 1920 to 1921, Proctor worked on the commission in his Palo Alto, California, studio on the campus of Stanford University. Once the model was complete, Proctor sent it to New York to be developed into a monumental plaster figure. Later, when Proctor was asked why he had chosen to represent Roosevelt in the uniform of a Rough Rider, he gave as his reason that “Dr. Coe wished an equestrian statue, and to my mind, the Spanish War period was the one to choose.” Proctor also felt that Roosevelt as a soldier presented a “picturesque” air, and that his participation in the Spanish-American War—from which Roosevelt returned to a hero’s welcome—had led to the governorship of New York state and finally to the presidency of the nation.

In early 1922, the heroic-size figure in plaster (now in the collection of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West) was finished, approved by Dr. Coe and the Roosevelt family, and sent to the Roman Bronze Works in Brooklyn, New York, for casting. Proctor executed the work in the Beaux-Arts style, characterized by monumental scale, idealized form, and generalized detail. The style had triumphed in Chicago at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, where Proctor was designing and making a number of sculptures for the exposition. It was there that Proctor first met Teddy Roosevelt, who would later come to Proctor’s studio to see the progress Proctor was making. Because bronze is a dark material, it was necessary to enliven or animate the Rough Rider, an effect Proctor achieved by modeling a textured surface that created a rippling effect as light and shadow played over the surface of the sculpture, suggesting the illusion of a fleeting moment.

On October 8, 1922, the finished bronze statue arrived in Portland aboard the steamer Ohioan, making the trip from New York via the Panama Canal. The following morning, it was lifted from the hold of the ship, greeted by cameramen and news photographers, and stored in a warehouse at the dock prior to moving it to the installation site opposite the Ladd School in Portland.

The politics of site selection

However, the selection of the site posed a problem from the beginning. According to a Portland newspaper, the site selection committee chose the Park Blocks site at Park, West Park, Jefferson, and Madison Streets, opposite the Ladd School, as early as March 1922. A petition favoring the site, signed by the eight hundred students of the Ladd School, was presented to the committee at that time.

Nevertheless, by June of that year, a decision had still not been reached. Both Proctor and Coe were opposed to placing the monument in the Park Blocks; it was, at best, a second choice. Their preference was for a triangular plot of ground at Chapman, Nineteenth, and Washington Streets. The previous autumn, in the Portland press in late October 1921, Proctor gave his reasons for opposing the location of his monument in the Park Blocks: “I’d like to see it there [the triangular plot] rather than in a park. I don’t like things put away where people have to make a trip to see them.” Proctor wanted the greatest number of people possible to see his monument, and he would be assured of this if it were placed at Chapman, Nineteenth, and Washington Streets.

There were problems to overcome with both sites, though. In the case of the Park Blocks site opposite the Ladd School, many Portland citizens objected to the removal of trees, on which Coe insisted. Even though he was reluctant to see healthy trees removed, it was an action he considered necessary to protect the monument from possible damage in the event of a tree falling.The difficulty with the triangular plot lay in persuading a group called the David Campbell Committee to give up the land that had been set aside for a monument to commemorate Campbell, a former fire chief who died in the line of duty a few years earlier. By mid-June 1922, though, the press felt confident enough to report that the Roosevelt statue location was near solution, “and that any obstacles will be cleared away…regarding the use of the triangular plot of land at Nineteenth and Washington Streets.”In the meantime, Coe hinted at the possibility of choosing another city for his monument. Coe said that “many cities other than Portland sought the statue,” but that “naturally he would like to see the statue located here” in Portland. This remark clearly indicated Coe’s increasing frustration with the committee’s inability to reach a decision on the monument’s location.

Ultimately, the David Campbell committee was not prepared to part with the land unless public sentiment indicated a desire to see the monument placed there. This was not forthcoming, though, and in late June 1922, the selection committee—with Coe present—made a decision in favor of the Ladd School site.

Post 215

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.