The Wild West in the Keystone State, Part 1 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2012

The Wild West in the Keystone State

Part 1

“Is the show in town?” asked the stranger of the native.

“Yes, just at present,” was the reply, “but in an hour or two, the town will be in the show.”

—Harrisburg Patriot, September 12, 1895

By Wes Stauffer

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West toured America and Europe 1883–1913, making 191 visits to Pennsylvania. Using area newspapers of the day to tell the story, Wes Stauffer writes about the Keystone State and how it affected William F. Cody, as well as the ways in which the show, in turn, affected Pennsylvanians. Starting with the passages below, Stauffer focuses on the Wild West show itself—logistics and effects—reminding us once again that Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was a colossal undertaking.

• • • •

On Wednesday, September 11, 1895, the Harrisburg Opera House in Pennsylvania reported a slim attendance at the evening performance of Three Jolly Old Chums. No matter how jolly the chums on stage, earnings did not make for merry management in the opera house that evening while Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World wowed large crowds in its open air arena elsewhere in the city.

• • • •

In 1901, the mighty Pennsylvania Railroad recognized the futility of trying to make employees report to work at the booming Altoona railroad shops and declared a holiday when Buffalo Bill’s exposition kicked up dust in town.

• • • •

Marketgoers dropped their coin at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and not into York shopkeepers’ pockets on Friday, May 22, 1908. The York Gazette reported, “When a show is in town…the city markets appear…deserted. In fact, the markets were the dullest of the season…”

Moderately priced fish in large quantities could not lure buyers in although, “The attendance of farmers for a short time was very encouraging, but this did not last long when the band began to play at the ‘Wild West’ show.”

• • • •

In March 1898, shortly before the show season opened, Buffalo Bill stirred up a buzz when he arrived in Coatesville. After rounding up his stock (six bison and a couple hundred horses) from local farms, “A large number of people gathered at the [Pennsylvania Railroad] freight station to see them loaded into the cars.”

The Wild West comes to town

A route book from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West states that in 1898 the show transported 329 show horses along with six mules for performances and an additional 118 draft horses to haul the show’s tents and supplies between rail yards and show grounds. At least six bison traveled with these horses. In 1899, traveling with an equally sized herd, agents for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West purchased 12 tons of hay and straw plus more than 200 bushels of feed from C.F. Finegan and Company in Chester, Pennsylvania. This fed the Wild West’s stock for the one day that the show performed in Chester.

Area farmers profited from feeding contracts and stable leases, while local businesses benefited from feed sales, veterinary and farrier needs of the livestock, as well as room and board for the show’s performers. On March 24, 1902, the West Chester Daily Local News reported:

• • • •

The big Wild West show of Hon. W.F. Cody, “Buffalo Bill,” is rehearsing at the farm where the animals are kept over winter every year….A large number of cowboys and Mr. Cody are at the place, the latter superintending the work. There were a large number of visitors from Coatesville and other places at the farm yesterday to see the horses and the six buffaloes. Late last season a large number of horses belonging to the show were killed in a railroad wreck and new ones have since been purchased. It is necessary to train the new animals for their various tricks and to get the entire show into shape for the road. It will start out for the season in a few weeks.

• • • •

Busting bucking broncos also drew crowds, and Wild West press agents recognized the excitement it generated. Earlier, one wrote in 1897, “As an aid to digestion riding a bucking bronco may be recommended—It is unique in this—that there is nothing like it. As an exercise it combines the advantages of riding on an express wagon without springs and traveling up and down on a swiftly running elevator.” This sounds more like a recipe for indigestion! Tough cowboys and Indians who dared ride unbroken horses discovered, “there seems to be no fixed limit as to the number of revolutions per minute” attained by a bucking bronco. “It may stand up or lie down, or ‘just buck,’ but, whatever it does, it does thoroughly and with exceeding promptness.” Often, the riders promptly needed a doctor.

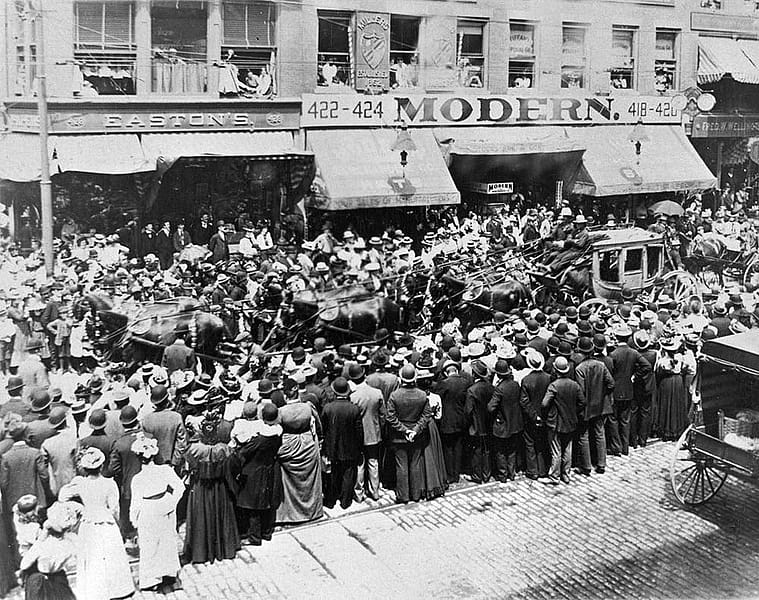

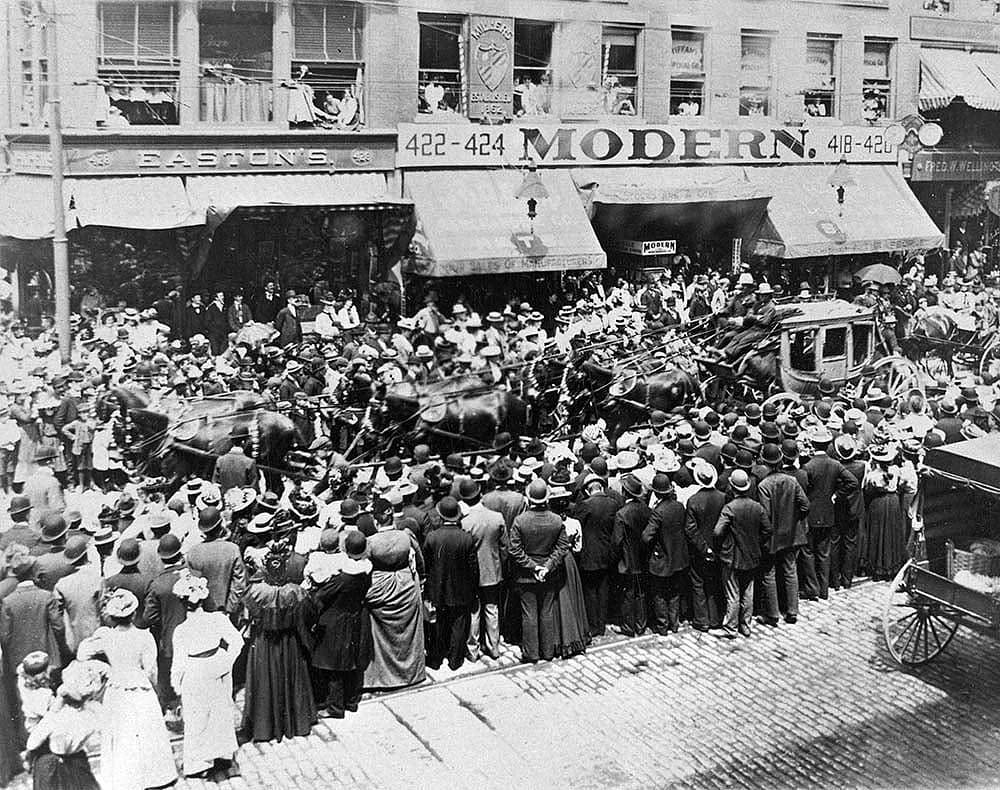

The show’s parades were popular with townsfolk, too. In the summer of 1897, Buffalo Bill led the colorful Wild West parade through Harrisburg’s streets riding in a carriage pulled by two white horses. “The Prince of Showmen,” his hair a bit grayer than when he last visited, “was a picture in his broad slouch hat and double-breasted coat, with his long hair waving about his shoulders,” a writer for the Harrisburg Telegraph observed. The writer continued, “It isn’t often our citizens can stand at their own doors and witness a cavalcade of natives, such as was presented to our wondering eyes in this morning’s parade of Buffalo Bill’s great show. So, to do honor to this red letter event the entire town forsook its usual haunts and camped on the curbstones. And it is safe to say not one of the great crowd—not even the habitual grumbler—was disappointed.”

Later that day, tickets sold out for the show’s two exhibitions when, according to the Harrisburg Patriot, “Perhaps never in the history of Harrisburg have two such enormous audiences witnessed any outdoor performance as assembled on the Sixth [S]treet grounds…” Enjoying a pleasant spring day with temperatures in the upper seventies, an estimated 26,000 people attended both shows including, “not a few of the German Baptist Brethren and their families…” A German Baptist conference convened the same day as Buffalo Bill’s show, and showmen mistakenly anticipated smaller crowds. Noting some of the strict churchmen at the Wild West, their presence indicated that, “either the peculiar fascination that the circus has for the average person was too strong…or they deemed the performance instructive, rather than amusing.” That day, approximately a thousand spectators watched from behind ropes in the standing-room-only section at each performance, and another four thousand disappointed citizens went home unable to get tickets at all.

The Wild West show by the numbers

From a financial standpoint, Wild West management took the show where the people lived and where it could enjoy the largest crowds. Pennsylvania’s economy boomed at the turn of the twentieth century (fueled by industry and natural resource extraction) and provided a rich pool of humanity from which to feed the coffers of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Some revealing facts emerge from a quick analysis of statistics contained within the 1899 show season Route Book.

During the five years 1895–1899, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West played to more towns than during any other time in its history, traveling 49,172 miles throughout the United States by railroad, an average of 9,834 miles per year. During that time, 10 percent of all the show’s stands (each in a different town) appeared in Pennsylvania (63 out of 632). New York hosted 10.1 percent, and Massachusetts hosted 7.8 percent to round out the top three venues at this time.

Seen through twenty-first century eyes, the Wild West tour schedule appears grueling. In 1898, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West covered a total distance of 10,253 railroad miles, barnstormed through 26 states, and erected its tents in 133 different towns. In 200 days, the Wild West performed 347 shows, not including parades. Of course the show’s hardy performers, all of them rough and tumble men and women, met the challenge. They faithfully delivered “an apocalypse of horsemanship, living romantic history” and “heroic, realistic action” day after day.

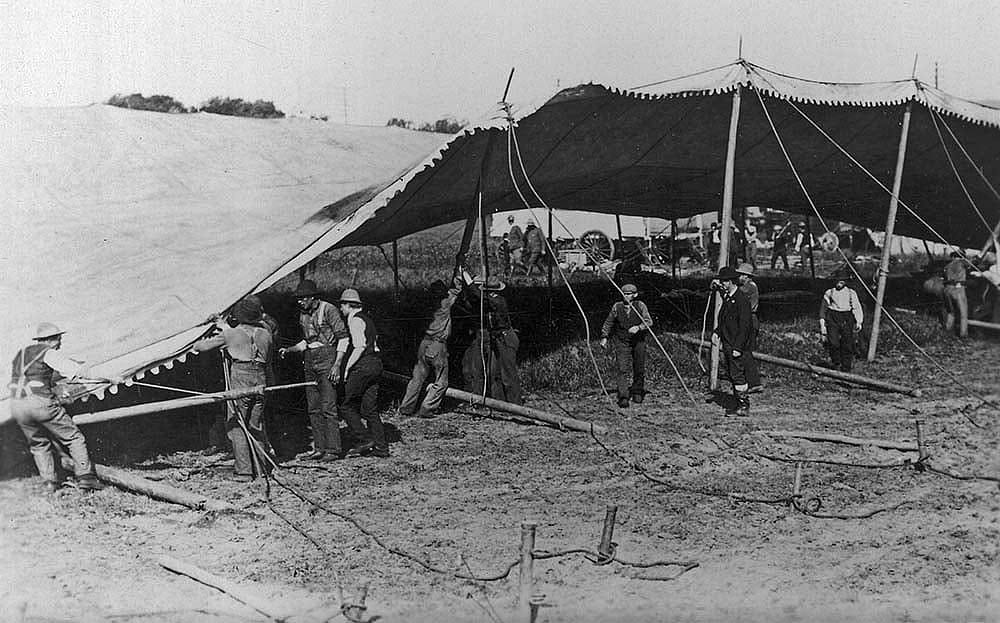

Buffalo Bill traveled with an entourage displaying military precision when transporting and erecting the show tents. In fact, European armies modeled their railroad movements and logistics after the Wild West’s efficient operation which would later contribute to the conduct of World War I. In 1898, Colonel Cody’s “army” consisted of 467 people, more than 450 horses, 35 baggage wagons, two water tanks, two steam engines (to generate electricity), four buggies, two prairie schooners, two field pieces, two caissons, as well as the Dead¬wood stagecoach.

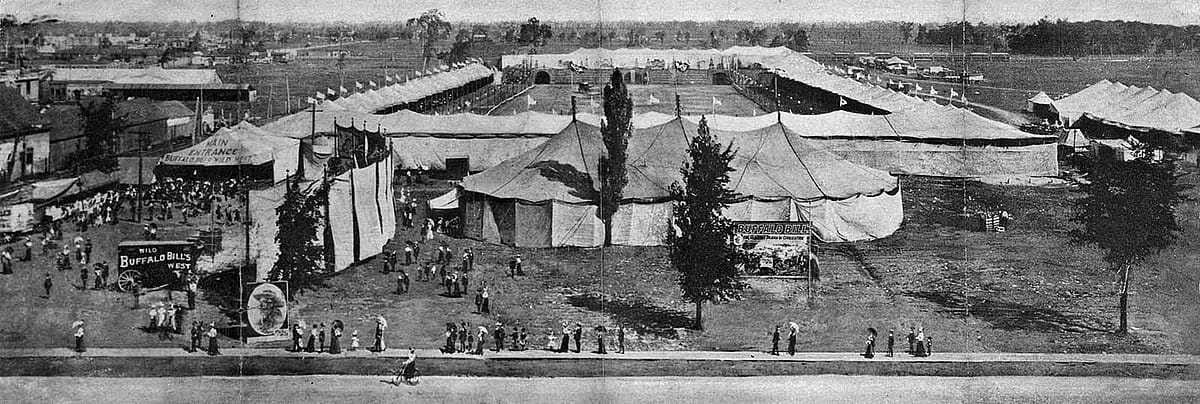

Lighting equipment included the double electric dynamos (“the largest portable ones ever made”) generating 250 candlepower as well as 76 arc lamps strung around the arena. The horseshoe-shaped canvas-covered bleachers seated 20,000 spectators and encompassed a five-acre arena. Show tents consisted of 23,000 square yards of canvas, needed 1,100 tent stakes, used twenty miles of rope, and required 11 acres of show grounds.

Typically, advance men arrived a day or two before the show to purchase supplies. In 1908, while in York, Wild West agents purchased $200 worth of hay, straw, and oats from Strayer and Brothers Company. In 1911, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Far East traveled with 600 head of stock (including elephants) which consumed 20 tons of hay and 300 bushels of oats during its one day stand in Wellsboro, Pennsylvania. Two years later, the York Daily noted the presence of Wild West purchasing agents in York the day before the “Two Bills Show” performed and noted that the show’s caterer, responsible for feeding 780 people three times a day, routinely purchased all supplies from the merchants of each town where the show performed.

After the evening performance, workers disassembled everything, hauled it all to the rail yard, and loaded the show trains which traveled through the night to the next town. The mess wagon left the show grounds first so it could roll off the train early in the next town, maximizing the cooks’ preparation time to feed the cast and crew. During the train ride, the company squeezed in a little sleep on the crowded, noisy, and swaying railcars.

William F. Cody spoke highly of the arena which his Wild West transported from city to city and erected for each show. In the final analysis though, which arena did Buffalo Bill really ride into? An arena shaped like a horse-shoe, lit by double dynamo-powered lights, and seating 20,000 people? Rather, Buffalo Bill rode into the larger arena of Pennsylvania where the entire state watched his show with a unique perspective into the changes taking place in American society at the end of the nineteenth century.

An independent historian, Wes Stauffer earned a master’s degree in American Studies from Penn State’s Harrisburg campus. His thesis explored William F. Cody’s Wild West connections to Pennsylvania. His resumé includes work as an archaeologist and in wildlife conservation.

Post 230

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.