The Wild West in the Keystone State, Part 2 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2012

The Wild West in the Keystone State

Part 2

By Wes Stauffer

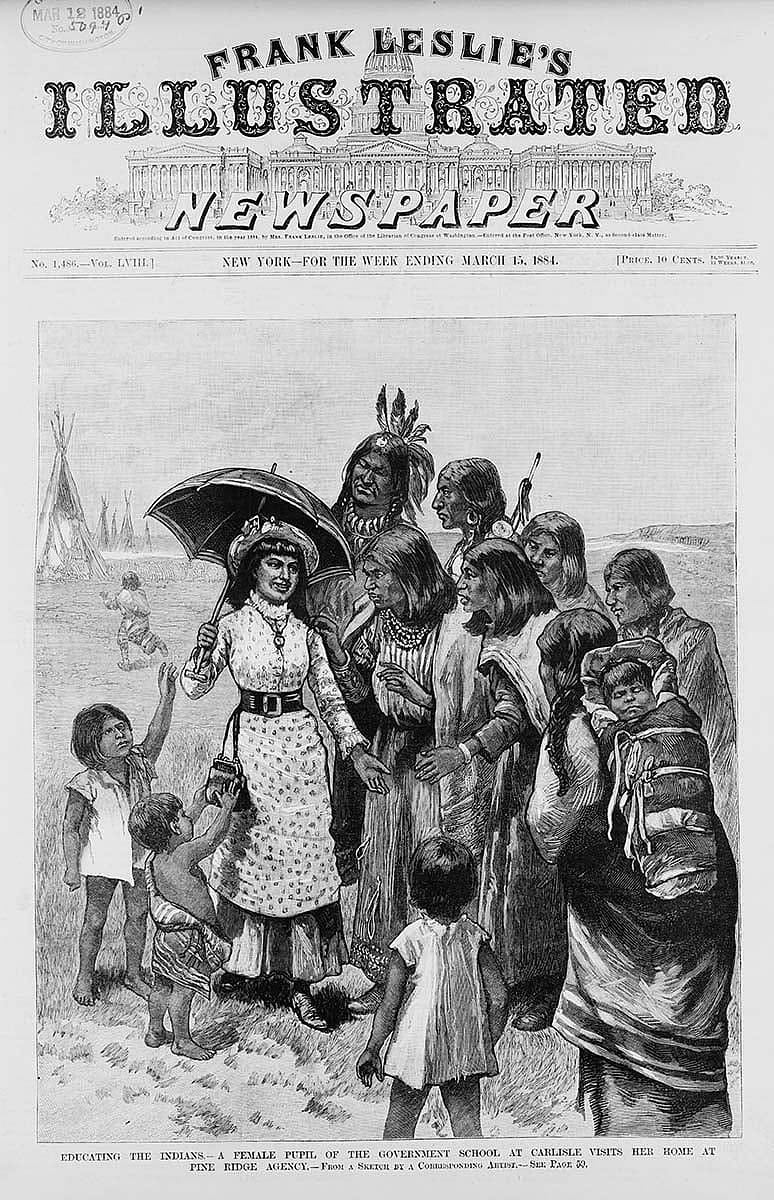

In the previous issue of Points West, historian Wes Stauffer used area newspapers of the day to tell the story of William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody in Pennsylvania, especially the logistics and effects of Cody’s Wild West show. In this excerpt from his thesis, Campfires, Conflicts, and Colonel Cody, he continues the story with the effect the Wild West had on Henry Pratt’s Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

While most people enjoyed Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in south central Pennsylvania in the late nineteenth century, not everyone approved of the role of Native Americans in his show. For example, Edward Marsden (1869–1932), of the northwestern Tsimshian Tribe, worked as a Presbyterian minister, educator, and missionary to Alaska Natives, and advocated for the rights of Native Americans and their higher education. On January 24, 1896, in the Carlisle Indian Helper, a publication of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School located in south central Pennsylvania, Marsden revealed his impressions of Native Americans in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Encountering performances while traveling throughout New York, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia during the summer of 1895, Marsden observed:

• • • •

…that is not the true Indian. You are deceiving the public. You are making money by upholding a bad relic of heathenism. You are inviting much ridicule and mockery upon William Penn’s intimate friends. You are disgracing the modern American civilization. No, that is not the true Indian. Just give him a fair chance, and he will soon find his way into the pulpit, the legislative hall, the commercial house, and the scientist’s laboratory, as others of his own race have already done.

• • • •

These words echo the mission of the Carlisle School which hoped to steer Native Americans away from their cultural ways and transform them into the school’s version of an ideal American citizen. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West ruffled some feathers in Carlisle, and Colonel Cody knew about the sharp criticisms which flew his way like proverbial arrows.

Captain Richard Henry Pratt (1840–1924) founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1879 and served as its director until 1904. Carlisle Indian School’s curriculum stressed learning English and vocational training, which included living and working with local families and businesses. In Carlisle’s boarding school setting, administrators required Indians to shelve their native fashions, to cut their hair, and to dress in street clothes. Notable graduates included talented football player and Olympian Jim Thorpe, and Charles Bender, Hall of Fame pitcher for Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics (1903–1917).

Pratt and other administrators at Carlisle School, aware of the popularity of wild west shows, believed they demeaned Native Americans. However, in 1897, the school allowed some of its students to attend the performance in Harrisburg. The Carlisle Indian Helper’s ghost-writing editor commented on August 6, 1897:

• • • •

A few of the students were allowed to go to Harrisburg yesterday to see Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Carlisle’s plan is to give full personal liberty to students in so far as it is practicable. The hope in giving this liberty was that those who should witness the disgraceful exhibition of the so-called savagery of their kin, would have intelligence enough to see that the whole thing is only a bold scheme to get money out of portraying in an exaggerated and distorted manner the lowest and most degraded side of the Indian nature. Only the SAVAGE in the Indian does Buffalo Bill care to keep constantly before the public gaze, and it is only the SAVAGE in the Indian that a certain ignorant, excitable element of society pays fifty cents and a dollar a seat to go see. Carlisle tries to bury the SAVAGE that the MAN in the Indian may be seen. Those who cannot see how such shows keep alive the little spark that the world delights to call savage, and how encouragement of the same injures the cause of Indian education, must truly be blind.

• • • •

Sharp words such as these reflect Pratt’s belief that all aspects of Native American culture, “savage” in his mind, needed to be eradicated. In keeping with this philosophy, any effort to preserve the Indian way of life promoted savagery and hindered education. Furthermore, he believed that all wild west shows exploited Indians.

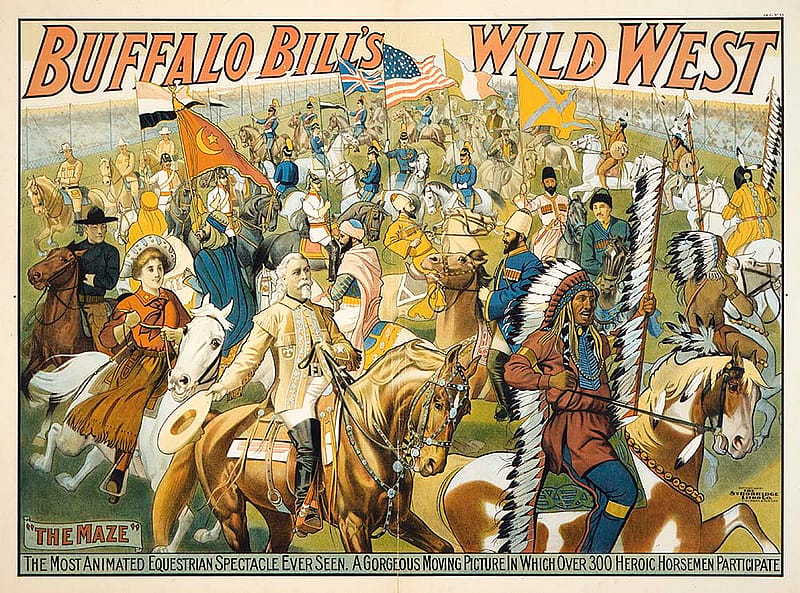

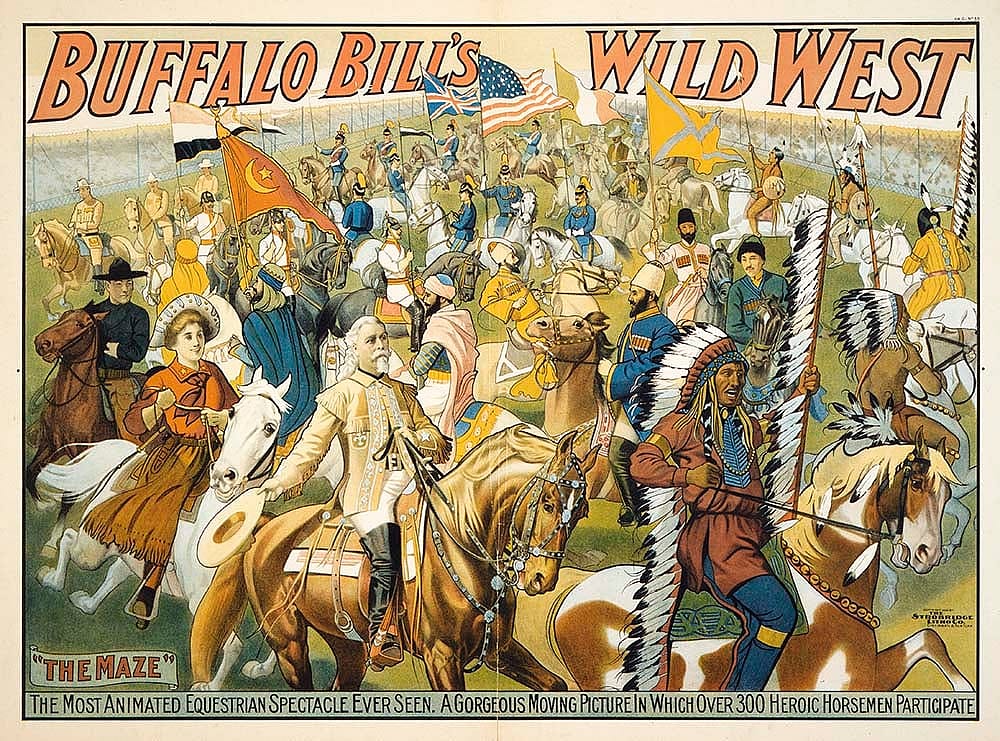

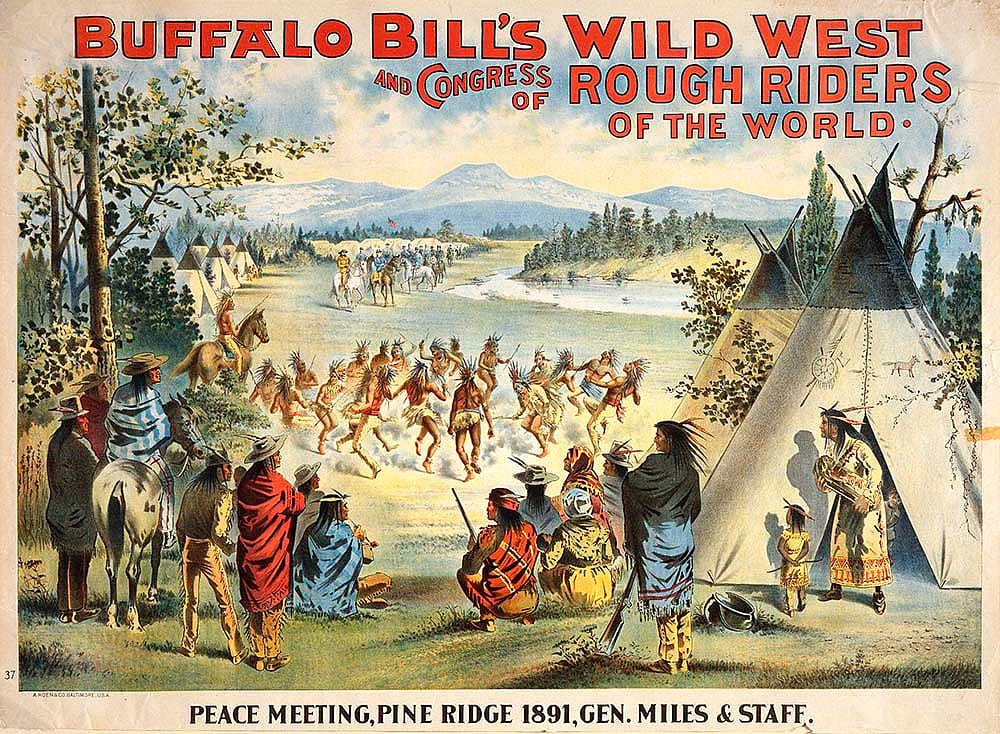

Col. Cody was quick to respond to criticisms such as these. A showman and businessman, he understood the important role that Native Americans played in his production. He also respected them and demonstrated interest in their culture. In 1898, Buffalo Bill brought his Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World to his “critics’ arena” in Carlisle. On Friday, June 24, 1898, workers erected a grandstand on the grounds at College, Walnut, and Willow Streets, and a souvenir book from the show says this of “Nature’s Nobleman”:

• • • •

Do not ignorantly and unjustly teach your children to hate, fear and despise the American Indian. He will soon be but a memory, and his character, as estimated by those who have best known him and hardest fought him, deserves that…memory should recognize and perpetuate his many noble qualities and virtues, which may well be emulated for all time to come… That renowned Indian fighter, General Nelson A. Miles…declares that he has no sympathy with that view which would debar the Indian from admission to the brotherhood of man, brands as false the brutal epigram, erroneously attributed to General Sherman, that “the only good Indian is a dead Indian,” and speaks admiringly of him as a diplomatist, a statesman, a warrior, and a friend…. Col. W.F. Cody, who fully subscribes to the opinions expressed above, while once among the Indians’ most active and dreaded foes is now regarded by them as their truest friend and safest counselor, and they not only place the most implicit reliance in his word, but solicit his advice on all important matters—an illustration of magnanimous admiration and forgiveness others might emulate with profit.

• • • •

Cody praised the “many noble qualities and virtues” of Native Americans and stated that they should be imitated. Once enemies on the field of battle, former foes forged friendships and respected the strengths each demonstrated in their earlier struggles on the Plains. Cody affirmed the Indians’ admirable roles as diplomats, statesmen, warriors, and allies. The assertion that the Native American “will soon be but a memory” echoed contemporary feelings within their own community.

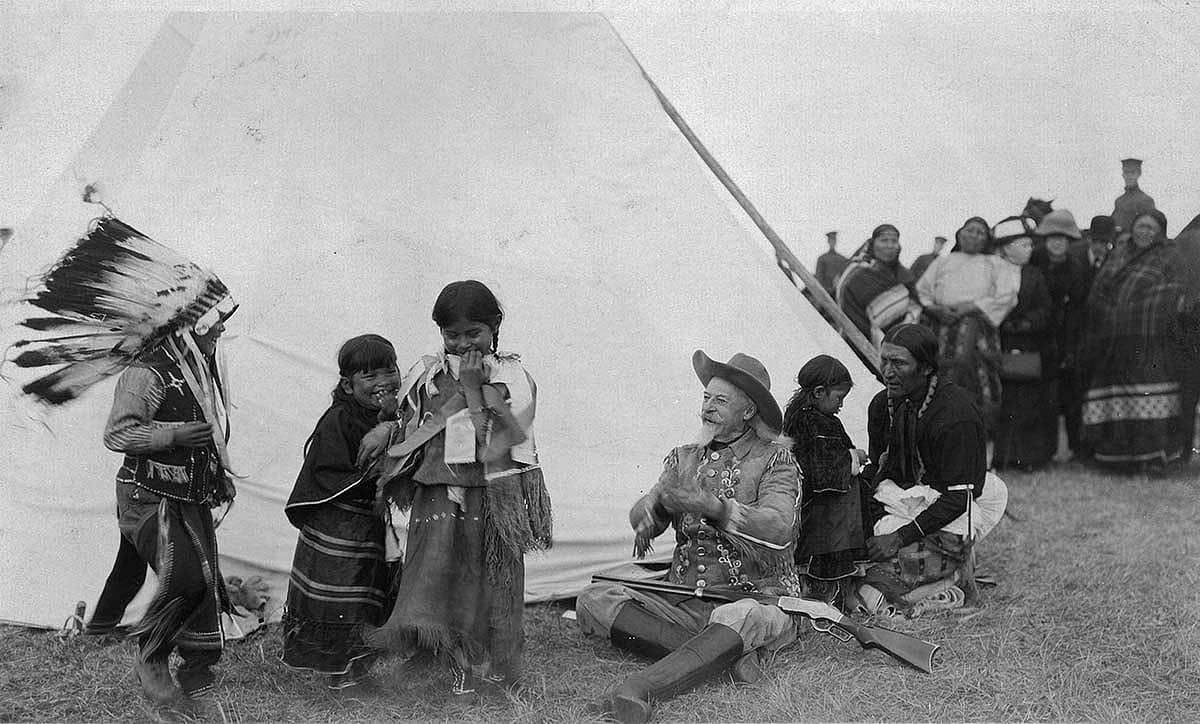

Carlisle Indian School administrators allowed their students to attend Buffalo Bill’s Wild West ad Congress of Rough Riders of the World again on Friday, June 24, 1898—and attend they did. On that day, the Carlisle Daily Herald records that “The Indians in the parade were profuse in saying ‘How’ (their way of uttering, How-do-you-do?) to the Indian School pupils along the line of march.” During the afternoon performance, Captain Pratt and the teachers, employees, and pupils from the Indian School “occupied prominent positions in the audience,” guests of Colonel Cody. Shows such as these certainly left an impression on the students of the Indian School; although not always to the pleasure of the administrators.

Excited by the show, at least one student ran away, presumably to join the Wild West, but unfortunately, tragedy resulted. “An Indian lad, 15 years of age, ran away from the Carlisle Indian School, on Saturday night, to follow the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show, and a few hours later a telegram to the school authorities announced that he had been killed by a train at Mexico, Juniata [C]ounty, a station on the Pennsylvania Railroad. The body was brought to the school on Sunday and was interred at the school in the evening.” The article closes by informing the reader that “The lad was of the Oneida tribe and was a wayward and incorrigible boy.”

Several graduates from the Carlisle Indian School did in fact join Buffalo Bill’s Wild West including Luther Standing Bear, a Lakota Sioux from South Dakota; Sammy Lone Bear, an Arapahoe; and William Brown, also Lakota Sioux. One of the first students to enter Captain Pratt’s school in 1879, Luther Standing Bear graduated in 1883. He made good use of his education by teaching, ranching, serving in ministry, and acting as an interpreter. In 1902, he joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West for a winter tour in England. A responsible individual, he supervised and advocated for the seventy-five Indians in the show. Standing Bear spoke well of Buffalo Bill and his Wild West, and he described some of his experiences in his autobiography, My People the Sioux.

On one occasion while in Europe, cooks served the show’s Indians a second rate meal of leftovers. Standing Bear immediately brought this to Colonel Cody’s attention. Upon hearing the concerns, Buffalo Bill’s eyes snapped as he arose from the table. Standing Bear wrote:

• • • •

“Come with me, Standing Bear,” he [Cody] exclaimed. We went direct to the manager of the dining-room, and Colonel Cody said to him, “Look here, sir, you are trying to feed my Indians the left-over pancakes from the morning meal. I want you to understand, sir that I will not stand for such treatment. My Indians are the principal feature of this show, and they are the one people I will not allow to be misused or neglected. Hereafter see to it that they get just exactly what they want at meal-time. Do you understand me, sir?” “Yes, sir, oh, yes, sir,” exclaimed the embarrassed manager. After that, we had no more trouble about our meals.

• • • •

Beyond his personal commitment to the comfort and happiness of his Native personnel, the United States Government also demanded that Cody look after their well-being. The Harrisburg Telegraph reported, “When one of these Indians is granted leave of absence to travel with the ‘Great Wild West,’ Colonel Cody must file a bond with the authorities at Washington providing for the proper care of the redskin and his or her swift return to the respective reservation at the expiration of six months from time of filing bond.” However, the Indians meant more to him than earnings at the end of the day. More than just business assets and wards, Cody (who grew up with Kickapoo friends in Kansas) took a genuine interest in their welfare.

Buffalo Bill commonly discussed Indian affairs with Standing Bear during their time together. Cody offered to represent Standing Bear’s tribe to President Roosevelt and, according to Standing Bear, “use his influence to help my people, providing he could get the authority from Washington. He asked if I would write home and ask all the old chiefs to appoint him as their helper. He said he would then engage some good attorneys to bring the grievances of the Sioux tribe before the President.” The tribe refused Cody’s assistance. Perhaps political ambitions influenced William Cody’s offer, but Standing Bear stated, “…Buffalo Bill gave up the idea, and once again we failed in securing someone who would take an interest in our welfare.”

When the winter 1902–1903 tour ended in England, Cody settled accounts with his company of performers. In addition to receiving their wages in full, all of the Indians received a new suit. For his service, Standing Bear noted that he received a bonus of fifty dollars cash from Buffalo Bill and said, “He said that was in appreciation of the good work I had done in keeping the Indians sober and in good order.” Summarizing his experience, Standing Bear wrote:

• • • •

…I am proud of the success I had while abroad with the Buffalo Bill show, in keeping the Indians under good subjection. It seems to me that when anyone joins a show of any sort, about the first thing he thinks of is drinking. That is wrong. It makes your employer angry and disgusted and does the person himself no good. It also takes courage to say “no” when thrown in with people who drink; but it pays. I respected my people and talked kindly to them.

• • • •

Standing Bear’s attitude reflects some of the values instilled by his Carlisle education. His responsibility and kindness paid dividends. He knew about critics’ accusations that Buffalo Bill exploited and neglected his Indian performers and Standing Bear refuted them.

After a short rest at his home in South Dakota, Standing Bear signed on with the show for the 1903 season. Unfortunately, Luther Standing Bear’s career with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West ended prematurely. On April 7, 1903, the show train in which Standing Bear traveled wrecked in Illinois while en route to New York, killing three showmen and injuring twenty-seven more. Standing Bear received severe injuries and initially medical personnel passed him off as dead.

Standing Bear recuperated, but never rejoined the show. He succeeded in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and affirmed the legitimacy of such employment for Native Americans. Using his four years of education received in Pennsylvania and exemplifying the successful aspects of the Carlisle Indian School, he retained his Native American identity and ultimately returned to the West where he worked to secure a better future for his people.

Captain Richard Pratt’s Indian School in Carlisle contributed significantly to the discussion about the future of Native Americans in the United States, as did Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Though Pratt’s philosophy differed significantly from Cody’s, Native Americans played a starring role in each institution. Buffalo Bill’s experiences in Harrisburg and Carlisle help illustrate the strong Pennsylvania contribution to the story of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

An independent historian, Wes Stauffer earned a master’s degree in American Studies from Penn State’s Harrisburg campus. His thesis explores William F. Cody’s Wild West connections to Pennsylvania. His resumé includes work as an archaeologist and in wildlife conservation.

Post 231

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.