On the Silent Hills Near the Little Big Horn

The relentless wind moved the sea of grass like ocean waves. Staring across the tranquil distance it was difficult to imagine the bloodshed that had taken place on these hills 145 years ago. Imprints from long overgrown rifle trenches seemed to be the only thing that showed the horrors this land had witnessed.

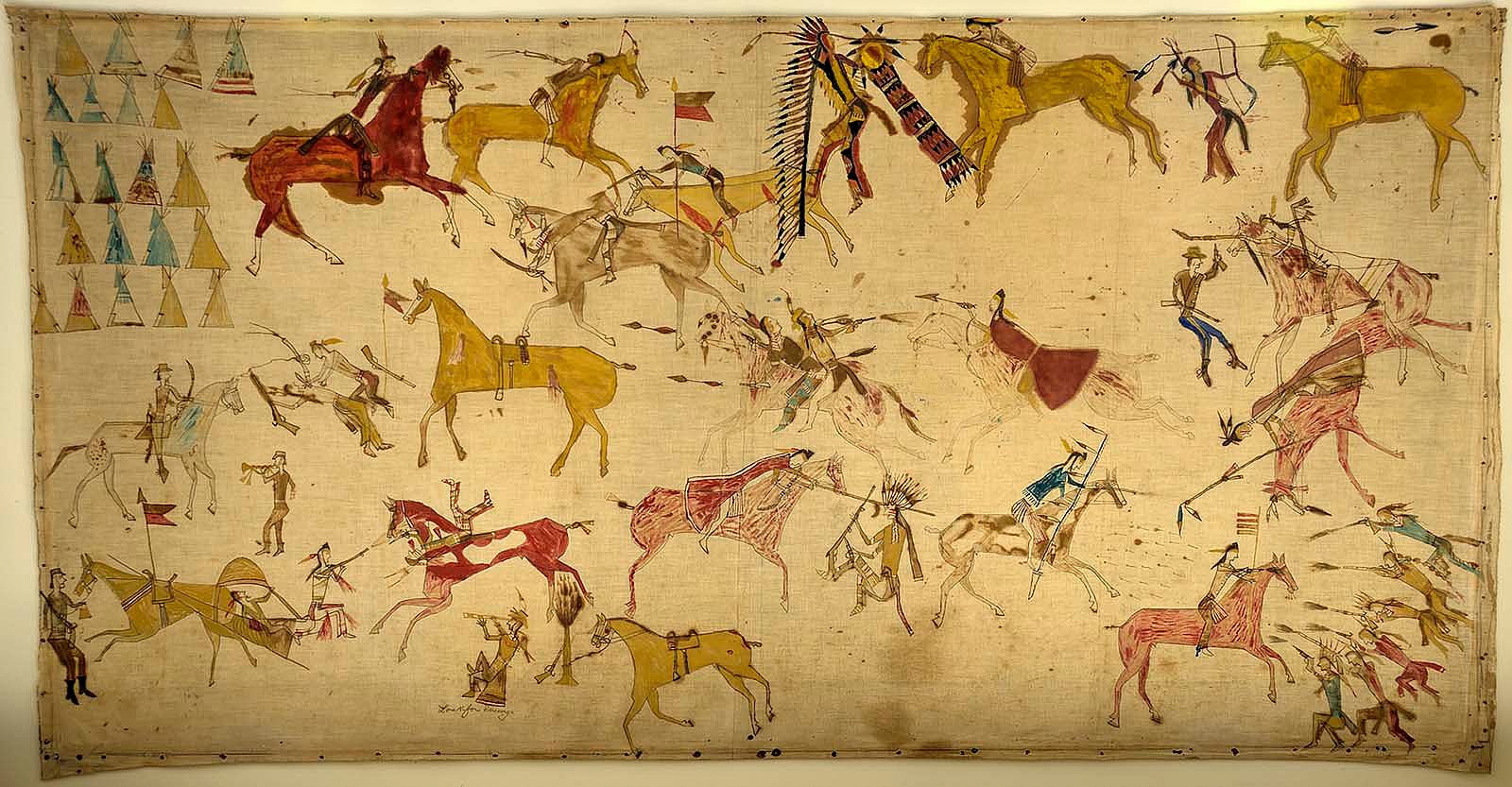

Two groups, one fighting to save a way of life, the other trying to push back those their president had labeled as “hostiles” met on the hills near the Little Bighorn River. The meeting which came to be known as the Battle of the Little Big Horn (or the Battle of the Greasy Grass), has fascinated historians and individuals since 1876. Join me as I share my experience on the banks of the Little Big Horn during the anniversary of this legendary conflict.

The Reenactment

Sitting near the banks of the Little Bighorn River on old, rickety bleachers I was stunned at the beauty of the landscape. The tall grassy hill poking up behind the meandering river only added to the reverence I felt for this place. I had always been interested in the battle since visiting Gettysburg and learning at the Center of the West about George Custer’s role in the American Civil War, but up until this weekend, I had only heard about Custer’s Last Stand from the side of the 7th Calvary. When I heard about the Real Bird Family Reenactment sharing the point of view of the Lakota, Arapaho, and Cheyenne tribes, I jumped at the opportunity.

With the echoes of the Crow anthem still hanging in the breeze, the story of the local Plains Indians was portrayed. As the narrator recounted stories and shared poems from his people’s beginning as hunter-gatherers, I was struck with admiration for a culture I had only read about up until this point.

I was saddened to hear the narrator recount the tragedy of the smallpox epidemic in the Native American tribes and to learn of the impact COVID-19 had on the Crow people in 2020. Then as the narrative continued with the discovery of gold in the Black Hills, the purpose of the U.S. army’s placement in Southern Montana became clearer.

The foundation for the battle had been set when Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and his 7th Calvary took center stage and made their last stand against Cheyenne, Sioux, and Lakota warriors as gun fire rang out across the hills. As Cheyenne Chief Two Moons recounted, the battle took “as long as it takes for a hungry man to eat his dinner” by the time the final US solider dropped to the ground.

As the gun smoke drifted away with the breeze, the consequences of the battle weighed on me. There was no real winner. Native American warriors who had just achieved victory on the banks of the Little Big Horn, would soon be forced to flee their homeland only to later return and be confined to life on a reservation. I saw those fallen soldiers and warriors as an ominous metaphor for the Plains Indian traditional way of life.

The Battlefield

With a new, more complete understanding of the battle’s context, I headed up the hill to walk the battleground. Journeying along the ridgeline, I saw the lack of cover available to both sides. The blistering sun reminded me how thirsty the soldiers and warriors must have been on those sweltering June days. I went by all the white or sequoia brown markers placed where American Soldiers and Native American warriors fell during the battle, thinking how each represents an irreplaceable life lost too soon, and mourning family left behind.

Standing in the center of the Indian memorial, I was touched reading the stories and seeing images of those who fought to protect their ancestral hunting ground. I stared at the large white monument marking the mass grave of American soldiers and turning the other way, I saw the Spirit Warrior Sculpture honoring the lost warriors. The monument fulfills its purpose well of joining both sides together. I loved reading the quote from Two Moons of the Northern Cheyenne, “Forty Years ago I fought Custer till all were dead. I was then the enemy of the Whitemen. Now I am the friend and brother, living in peace together under the flag of our country.” I hope we can continue to heed his words as we strive to live in peace.

Looking Forward

Situated in the remote, grassy plains of Montana, I am grieved that more people cannot go and experience the breadth of emotions available along the Little Big Horn River. Those hallowed grasslands gave me a greater understanding of and respect for the Native Americans and American soldiers who fought and died there in 1876. I hope you have the chance to visit the monument because the experience is indelible. If you are unable to travel to Southern Montana, I recommend reading this article to see how both sides have depicted the battle.

To finish, I would like to share a quote fittingly put on the visitor center at the national monument,

“Know the power that is peace” -Black Elk

Written By

Brennen Serre

Brennen Serre is a PR and Marketing intern at the Center of the West. During the school year, Brennen studies Finance at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. Having worked and volunteered for zoos and museums around the world, he is passionate for helping non-profit institutions achieve their missions. He enjoys hiking, listening to vinyl records, and cheering on his favorite college basketball team.