Tim McCoy and The Covered Wagon: the Birth of a Movie Star

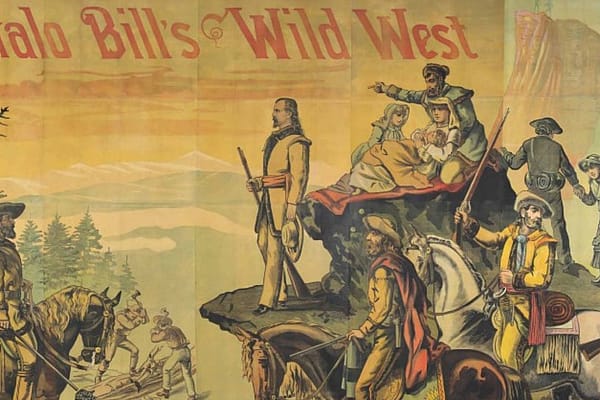

When Tim McCoy was eight years old, his father took him to a showing of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Tim dated his desire to be a Westerner from that point. He enjoyed his childhood in Saginaw, Michigan. He loved to watch the north woods lumberjacks swarm his town after the log drives in the spring. He boated on Lake Huron and played in a marching band with a collection of relatives. Tim had an eye for adventure. He was especially impressed when one day, standing on a railroad platform with his dad, he saw a broken-down old man. Wearing a wool coat. On a hot muggy day. Why? “That man,” Tim’s dad said, “is a good deal younger than he appears. He spent time at Andersonville prison camp during the Civil War. It took away his health and he wears that coat, always. He says it keeps away the chill.”

But nothing impressed Tim so much as the day he met Buffalo Bill. Ushered back into his tent after a Saginaw performance, young Tim McCoy was dumbstruck. He didn’t remember what was said, but he thought Cody “The most impressive man I had ever seen, unmatched either before or since.” Tim meant it, as we will see. “Years later,” he wrote, “I would have the opportunity of renewing my acquaintance with that remarkable gentleman, but for the time being I and my friends had to be content imitating Buffalo Bill and the Indians, by riding wooden broomsticks across the front yards and through the back streets of Saginaw.”

Tim’s family wasn’t impressed with his downwardly mobile choice of the profession of cowboy, but this did not stop him. In 1908, he was living with his mother’s two bachelor brothers and three spinster sisters in Chicago while he attended St. Ingatius’ Jesuit College. Latin was on the menu. Many of his classmates were studying for the priesthood. Tim blew off school for an entire week to watch the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Wild West Show. After Christmas, he slipped away to the train station. He had a toothbrush, one change of clothes, and enough money for a ticket. He was eighteen years old.

When the ticket agent asked him where he wanted to go, Tim didn’t know what to say. At random, he picked Omaha, Nebraska. It sounded Western, and it cost less than a ticket to Montana. Getting a job as a horse herder, he wound up in Lander, Wyoming.

Tim McCoy spent years roaming the Wind River Basin. Unlike other cowboys of his day, he made friends with the Arapaho Indians in the area. He pulled night guard with George Shakespear, a long-haired Arapaho who had grown up in a teepee. The other cowboys joked about how they were gonna tie George down and “roach” his long hair. It took a while for Tim to get George to thaw out, but he was persistent. And that’s how Tim learned Indian sign language.

Years later, in 1922, in Cheyenne, Tim received a visitor in his office: a casting agent from Famous Players-Lasky. He wanted 500 Indians for a movie, and heard Tim McCoy was the man to talk to. Now Adjutant General of the State of Wyoming, Tim had served in World War I as a member of the U.S. Cavalry. Tim originally tried to get involved when he wrote a letter to former President Theodore Roosevelt offering to raise a company of horsemen to fight. Roosevelt loved it. He sent Tim a telegram. “Bully! Do proceed!” The plan was rejected by Woodrow Wilson, but Tim managed to talk his way into the U.S. Cavalry anyway. Tim McCoy was a guy who made things happen. Now sitting in an office in Cheyenne in Army boots, he was bored.

McCoy’s friendly overtures to the Arapaho had not gone unnoticed. The Arapaho liked him enough that they even gave him his own name, High Eagle. History is full of whites who claim to have been adopted by Native tribes, but the Arapaho seemed to see Tim McCoy as sincere. And now the movie industry was planning a big epic. They wanted real Indians, real locations, and they had read about Tim McCoy. Mr. Lasky, the agent explained, wanted the picture to be as authentic as possible. “Don’t you speak that sign language of theirs? Then you’re our man.”

Tim was suspicious. He had seen how many times the Arapaho and other tribes had been, as he put it, “Taken to the cleaners.” As Adjutant General he had spent considerable time trying to get Arapahos who had served as Army scouts their pension money; no one had told them they were eligible.

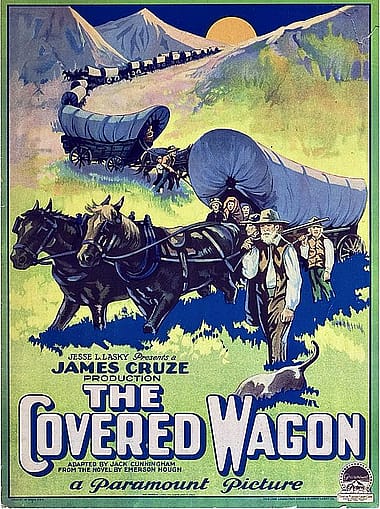

On-site Western films were a new thing. The first Westerns had been made in New Jersey. From there they went to California. A “town” called Inceville sprung at the mouth of Santa Inez Canyon, compete with Western sets. Today it’s a part of Pacific Palisades. The streets of Hollywood thronged with cowboys who had heard there was good money to be made falling off of horses for the movies. This new epic movie was called The Covered Wagon. It was based on a novel by Emerson Hough. The film location, near Milford, Utah, thronged with thousands of extras and hundreds of tents and teepees, not to mention horses.

Tim made sure the Natives would be paid — five dollars a day per adult, fifty cents a day per child — and that they would be fed. This was more than most reservation inmates made in a year. Cookfires featured roasting haunches of beef, which had been carted off from the cook tent. There was plenty of jerky for everyone.

In this way McCoy was following in the footsteps of his hero. One thing Buffalo Bill did for the Natives he employed was to get them off the reservation for a while; on movie sets and Wild West shows Indians could dress as they liked, see the world, and make a little money as opposed to literally starving on a reservation.

The Covered Wagon highlighted a strange thing about Wild West mythology: the movies and the real thing bled over into each other in the early days. The wagons used in The Covered Wagon were real wagons that had been used on overland journeys. Many of Tim’s Arapaho buddies, now commencing film careers, had been present at the signal battles of the Old West. The conditions for the cast and crew mimicked those experienced by pioneers. At one point a fierce blizzard blew through. The only comfortable people in the outfit were those living in teepees, which were quite warm. During the downtime the Natives ate, visited, and played rawhide drums. The white staff and actors shivered in Army-style tents. Finally they decided to shoot anyway. The scene of wagons staggering through a blizzard made the final cut.

At the grand opening, Tim stood on stage with about thirty Arapahos at Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood, where he conversed with them in sign language on stage to introduce the movie. Moviegoers were seeing the real deal: on stage with McCoy were Left Hand, who had fought Custer; Goes in Lodge, who fought the whites and later served as an Army scout, and Lizzie Broken Horn. Lizzie was actually a white woman who had been captured in 1865 when the wagon train she was with had been attacked. When her family finally tracked her down in 1902, she declined to go “home.” She was now Kills In Time, a redheaded Arapaho, married to a man called Broken Horn. I suppose Lizzie was repatriated at this point, but not in the way that anyone had pictured it out.

Tim McCoy, as you can see, cuts quite a figure. The runaway turned real-life cowboy was drafted to act himself. He eventually starred in over eighty Westerns and appeared on a Wheaties cereal box. In the 1950s he hosted his own TV show, where he gave history lessons on the Old West and showed his movies. Tim McCoy had got to the West early enough to rub shoulders with rustlers on the open range; he also made it into the zenith of the Western genre era, radiating out of small box TVs for viewers who lived far from the wide open he had lived long enough to see disappear.

Written By

Eric Rossborough

Eric has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the McCracken Research Library. Eric comes here from Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.