The Draw of Cody – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2019 – 20

The Draw of Cody: The Role of Place in Helping Make Artists Great

By Ruffin Prevost

It’s the incomparable landscapes. Also, the genuine locals. And the obvious history. The authentic, living West is here. Never underestimate the appeal of a chance to reinvent yourself in Cody, Wyoming.

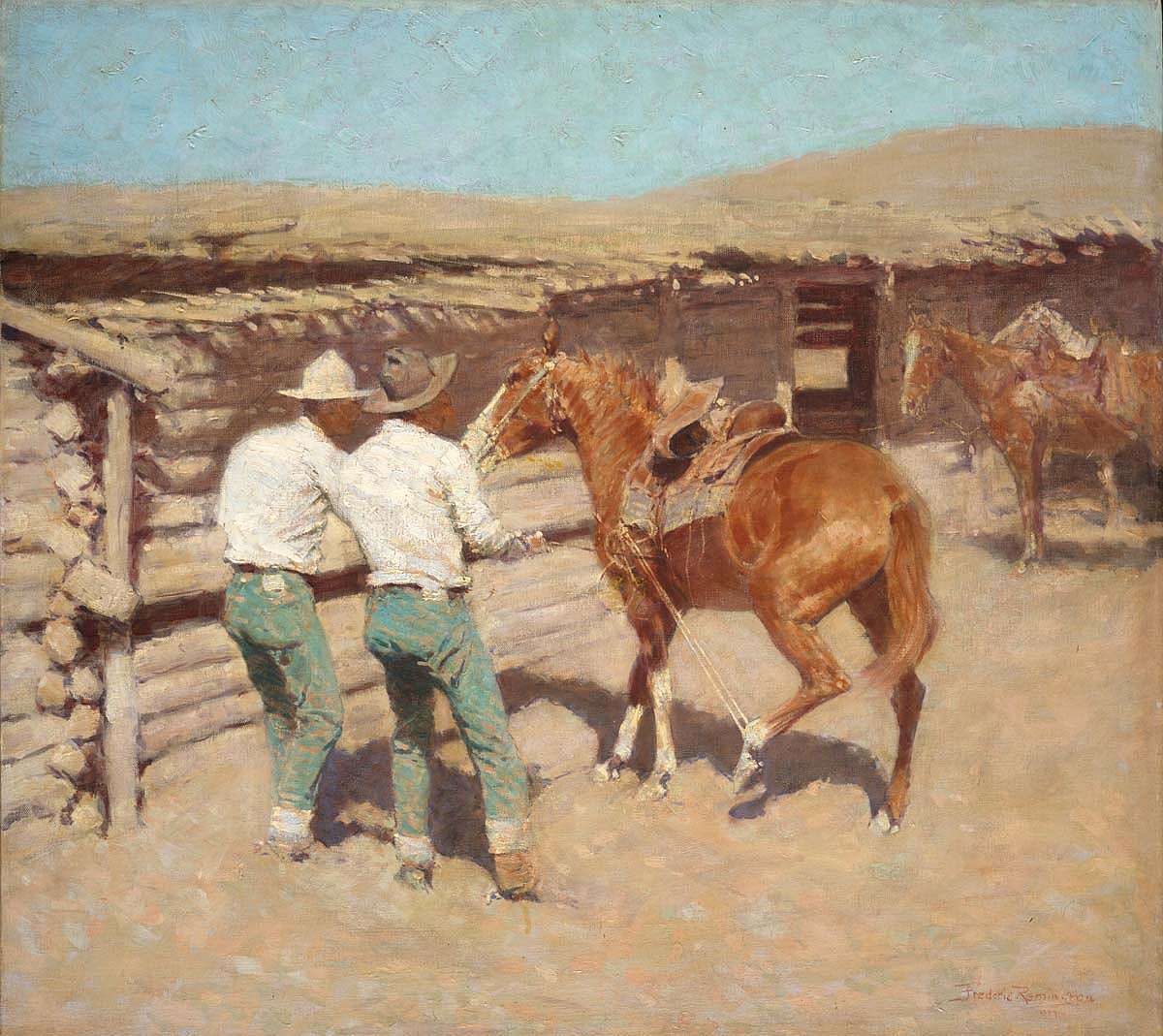

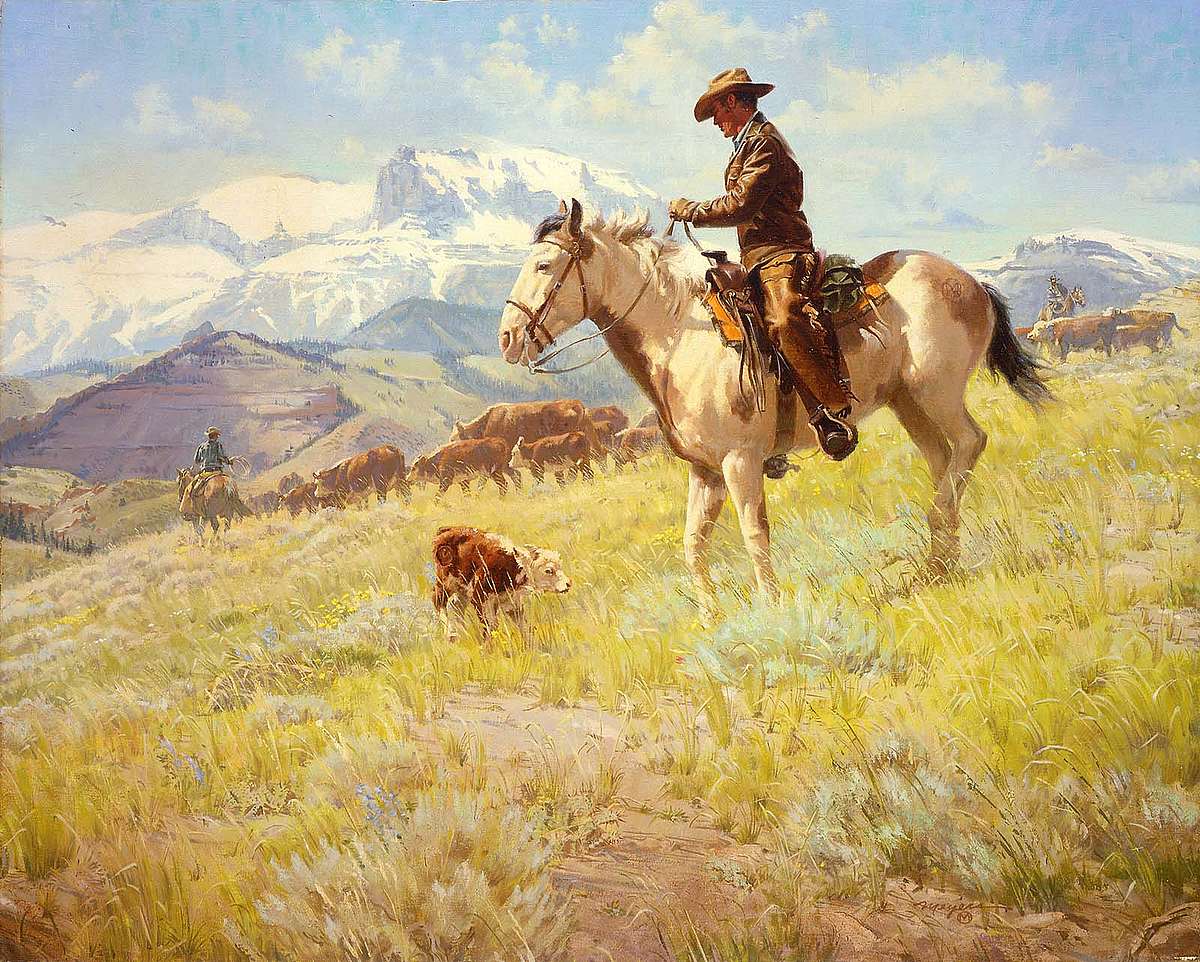

Those reasons all played a role in attracting a handful of artists who shared a common passion for Cody and the surrounding area: James Bama, Robert Meyers, Frank Tenney Johnson, and Frederic Remington. They each came at different times, but they have much in common. They all started their careers as illustrators and relied on photography as a tool in helping create acclaimed, fine art paintings that drew on Cody to help tell the broader story of the American West.

And in some ways, Cody may have played a role in helping make each of them a great artist. “Coming from an 18-story midtown Manhattan apartment building with a doorman to a place 36 miles outside of Cody was quite an adjustment,” recalled James Bama, who moved to the South Fork Valley in 1968, at the height of his career as an illustrator.

Along with his wife, Lynne, Bama first visited Cody at the invitation of his friend and fellow commercial illustrator, Robert Meyers. Both men worked for the same New York studio, and Meyers walked away from his illustration career in 1960 to buy and operate the Circle M Ranch. After a few trips to visit Meyers, Bama moved to the same ranch, creating fine art paintings by day and paperback book covers by night to pay the bills.

“There’s something about Wyoming that invites people to be what they want to be,” said Karen McWhorter, Margaret and Dick Scarlett Curator of the Whitney Western Art Museum. That was the case not only with Meyers and Bama, but also with “master of moonlight” Johnson, as well as painter and sculptor Frederic Remington.

Johnson had a studio in the North Fork Valley near Cody for most of the 1930s, making frequent plein air painting trips into Yellowstone National Park and the surrounding forests. Remington never lived in Cody, but spent time here drawing inspiration for works that would help define the West for generations. Both Johnson and Remington, like Bama and Meyers, started as illustrators, and would often use reference photographs to help inform their fine art.

Like Meyers, Johnson’s time in Cody was closely tied to dude ranching. Meyers’ cousin started Rimrock Ranch in 1926, said Gary Fales, who operates the ranch today. Guests can still stay in the “Artist’s Cabin,” which was Johnson’s studio until he died in 1939.

“Shortly after they started the ranch, the Depression came,” Fales said. “But Johnson had connections in New York and California, and kept the place filled with artists and other friends who still had jobs and money.”

Money was one reason all four illustrators sought to transition to careers as fine artists. But the freedom to draw, sketch, or paint whatever they wanted was paramount.

Pursuing work as fine artists was “a great opportunity to become more well-known,” McWhorter said. “But it was also an entry point to creative freedom that they didn’t have when working on commissioned pieces.”

Remington made a concerted effort in the latter part of his career to distance himself from his work as an illustrator, McWhorter said. Cody offered an authentic connection to the Old West that Remington saw slipping away elsewhere. Johnson spent his time around Cody working to perfect his technique for painting nocturnes—instantly recognizable twilight and nighttime depictions of horses, landscapes, and cowboys rendered in silvery blues and viridian greens.

Meyers, the least known among the four, was murdered in 1970, leaving behind a body of work that never quite achieved the full transition to fine artist as realized by the other three. Perhaps that’s because Meyers moved to Cody in 1960 to run a dude ranch, rather than to specifically pursue or perfect his artistic ambitions.

Bama still lives [Ed. note: James Bama passed away on April 24, 2022] in the North Fork Valley, although he no longer paints. At 93, he has long since achieved the kind of cult local character status he sought in his portrait subjects when he first arrived. [Ed. note: James Bama passed away on April 24, 2022]

“I like to paint old people, people with character, wrinkles,” he said, adding that he doesn’t miss painting.

“I’m not frustrated. Everything ends. Since kindergarten, I was copying the comic strips, Flash Gordon and Tarzan. Everything ends and I’ve had two successful, great careers,” he said.

For Bama, it was Cody’s local characters, while Johnson loved the area’s moonlight, hills, and horses, McWhorter said. And whether for artistic inspiration or for pursuing a new life on a ranch, Remington and Meyers saw in Cody an authenticity and connection to the past that was hard to find elsewhere.

“For different and also for similar reasons, they were all attracted to this place. It was fairly remote and therefore supported more of the traditional lifeways of the West,” McWhorter said. “A lot of people to this day still live here because they’re committed to living a more traditional life that’s closer to the land and older ways of doing things.”

“There’s no doubt this place had something to do with making all of these artists great.”

About the author

Ruffin Prevost is a freelance writer from Cody, Wyoming, and editor of Points West.

Post 327

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.