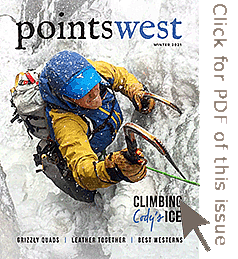

Climbing Cody’s Elusive South Fork Ice – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2021

Frozen Treasure: Climbing Cody’s Elusive South Fork Ice

By Ruffin Prevost

All kinds of people come from all sorts of places to search for all types of treasure around the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Big game hunters want to bag that elusive trophy. Miners have long sought gold and other buried treasure here. Many others hunt for coal, oil, and natural gas. Photographers spend days—even decades—searching for the perfect shot.

But the hills around Cody are arguably richer in one particular kind of treasure than any other place in the country. Fanatics come from around the world, and some even move here, to hunt for ice. Not just any ice, mind you, but tall, shimmering pillars begging to be conquered by elite climbers looking for singular, unforgettable experiences.

Less than an hour’s drive southwest of Cody, ice climbers gather each winter in the South Fork Valley to scale literal frozen waterfalls. Some are freestanding columns of ice—gargantuan icicles the size of grain silos—unconnected to anything but the ground below and cliff above. Others are towering, multi-leveled cascades of seemingly endless ice, stair-stepping into the winter clouds overhead.

Yet, even for most Cody residents, ice climbing is relatively unknown compared to Cody’s nightly summer rodeo, Yellowstone National Park’s abundant wildlife and thermal wonders, or even the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s sprawling campus of collections and attractions. But for top ice climbers, Cody is rightly famous for its frozen treasure.

With roots in mountaineering, and similar to rock climbing, ice climbing involves using specialized gear like ice axes and spiked boot attachments called crampons to aid climbers in ascending columns and walls of ice. The Cody area is home to the largest concentration of challenging climbing routes in the U.S., aficionados say.

“Cody is unique because it’s the only place in the continental U.S. that has this big valley of alpine wilderness full of so much challenging, or even intimidating, ice,” said Aaron Mulkey, a top ice climber who moved to Cody to pursue the sport.

Now in his mid-40s, Mulkey moved to Cody from Boulder, Colorado, in his early twenties specifically because the ice climbing opportunities are so abundant and challenging.

“The wildness, the adventure, and the potential for new routes—that’s what resonated with me,” he said. “Climbing was my focus. It wasn’t a social scene or dating. Climbing is what I wanted to do.”

The South Fork Valley is accessed by Wyoming Highway 291, which runs more than 40 miles along the South Fork of the Shoshone River before it dead-ends, making the area far less-traveled by tourists than the road to Yellowstone.

Rugged, remote, and isolated, the upper valley is home to several large, historic ranches, properties now prized as much for their scenery and recreational value. Aside from bison and caribou, every wild ungulate species found in the Northern Rockies can be spotted along the South Fork Valley: moose, pronghorn antelope, elk, mule deer, white-tailed deer, mountain goats, and bighorn sheep. And with all that big game wandering around, predators are always nearby, including grizzly bears, black bears, wolves, coyotes, and foxes, along with raptors like hawks and eagles.

A number of factors make the South Fork Valley the ice climbing paradise it has become, said Nathan Doerr, [former] curator of the Draper Natural History Museum.

“Amid the vertical cliffs and deep canyons that create the rugged topography of the South Fork Valley, geology, elevation, and climate come together to create a dynamic landscape,” he said. “Of the many distinct characteristics of the valley, its countless drainages, sheer rock faces and overhanging cliffs, and resulting waterfalls make it especially unique when it comes to recreation, particularly for ice climbing.”

“The layers of volcanic breccia, sandstone, and shale have been easily eroded by glaciers, water, wind, and gravity. The result has been drainages that are supplied by both ground and surface water.” Doerr said. “Given the high elevation of the surrounding mountaintops, cold temperatures, and angle of the sun, the water in the drainages begins to freeze, forming frozen waterfalls early in the season. As the angle of the sun changes over the winter months, other waterfalls freeze over, melting snow continually builds up the formations, and they last later into the season.”

Those natural processes and the ongoing freeze-thaw cycle mean the location, size, and composition of ice routes change continuously from fall through spring. Some routes appear only briefly when conditions align perfectly, making the hunt for frozen treasure part of the challenge of conquering a particular climb.

“One of the allures of ice climbing is a route can be there this year and not be seen for another 20 years,” Mulkey said. “I enjoy that hunt and the once-in-a-lifetime potential experience of finding a trophy piece of ice.”

Like many climbers, Mulkey documents his frosty conquests with jaw-dropping photos and videos on Instagram, Facebook, and other social media platforms. But he is also writing a guidebook to help climbers navigate the more reliably found and popular routes—climbs with names like Mean Green, Broken Hearts, and Bozo’s Revenge.

Though the sport is relatively new and has grown fairly slowly, climbers have been scaling ice in the South Fork Valley since the 1970s, said Bob Newsome, a longtime climber who started Cody sporting goods store Sunlight Sports in 1971.

Throughout the 1970s, Newsome and other climbers from around Cody began climbing ice near town, later expanding to the South Fork Valley and around Cooke City, Montana. Climbers from Bozeman were also part of the scene that saw early adopters improvising their own gear.

“We took old leather ski boots, peeled the soles off and had Waynes Boot Shop put a (custom) sole on them so they would stay rigid” for climbing vertical ice, Newsome recalled. Early ice climbers modified rock climbing equipment to create home-brew axes, crampons, and other ice gear until an industry grew up around the sport in the 1980s.

“Word started getting out that we had route after route, icicle after icicle in the South Fork, and people would just show up,” Newsome said.

Cody climbers and tourism boosters worked to publicize the area, and the local scene has continued to expand, with similar but less challenging scenes developing around Ouray, Colorado, and Bozeman, Montana.

An annual ice climbing festival in Cody that has been on hiatus in recent years is set to make a comeback in 2022, Mulkey said. And Newsome sees the sport continuing to slowly grow in the area.

That’s good news for winter tourism around Cody, as both Mulkey and Newsome said ice climbers are typically big spenders, investing thousands in gear alone.

Claudia Wade, marketing director for the Park County Travel Council, said Cody is “fortunate to be a world-class ice climber destination.”

“These enthusiasts come during the time of year when Cody lodging rates are at their lowest and coffee shops, restaurants, and breweries are less crowded,” she said.

“Less crowded,” of course, is also part of the appeal for Cody climbers like Mulkey and Newsome, who cherish the solitude and quiet splendor of winter in the South Fork Valley. It’s a spot that has more than enough ice to handle all comers, and abundant big, difficult ice to continually challenge longtime experts.

“A little bit of the attraction is doing something that not everyone else can do or wants to do,” Newsome said. “Why do people swim with great white sharks? There’s an exhilaration. I’ve scared myself on numerous occasions. It becomes a very personal and complex thing.”

Mulkey said he likes the “here today, gone tomorrow” nature of finding and climbing ice.

“Rock is always there. It doesn’t move or melt. Ice changes every year,” he said. “I can climb the same chunk of ice 10 times and it’s always different.”

“Then, it will literally melt and be gone. Three months from now, there’s no way you can get up the path I just climbed,” he said. “I’ve been in places where no one has ever stood before—I’m the only person. For me, that’s really cool.”

About the author

Ruffin Prevost is a freelance writer from Cody, Wyoming, and editor of Points West. He operates the Yellowstone Gate website and covers Wyoming and Yellowstone National Park for the Reuters global news service.

Post 339

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.