Why These Objects? A Closer Look at the Buffalo Nation Spotlights

As the opening of the Buffalo Nation spotlights approaches, a deceptively simple question emerges: why these objects? What makes them “spotlights,” and how do they help tell the larger story of Buffalo Nation?

The answer unfolds across the Center of the West, where each museum offers a distinct lens on the bison’s enduring presence. Together, these spotlights reveal the animal not as a single symbol, but as sustenance, subject, spirit, and catalyst for change.

Draper Natural History Museum

The Draper Natural History Museum’s spotlight explores both ancient practice and modern interpretation, focusing on bison jumps and the archaeological work that helps us understand them today.

In the left case, objects used in bison processing and crafted from bison materials anchor the story in lived experience. An obsidian scraper, a horn spoon, and a bone flesher speak to the immense investment of time and labor involved in bison jumps, as well as the animal’s many uses. These tools invite visitors to consider how bison shaped daily life, from food preparation and clothing to travel and seasonal movement.

The right case shifts to the present day and asks a different question: how do archaeologists make sense of vast bone beds left behind at bison jumps? Teeth provide one key. Because bison consume gritty diets that gradually wear their teeth at a predictable rate, archaeologists can estimate age by examining dental wear, most often in the lower jaw. These age profiles help reconstruct herd structure during a single hunting event. When combined with radiocarbon dating and site location, they offer powerful insights into how bison jumps were used across time.

Plains Indian Museum

In July 2025, the Plains Indian Museum welcomed artist John Hitchcock (Kiowa / Comanche) as artist in residence, with support from Interpretive Education’s Heather Bender. A returning artist with prior residencies in 2017, 2019, and 2022, Hitchcock collaborated with American artist Emily Arthur to create Buffalo, Deer, Bird, a monumental mural composed of more than 600 individual pieces.

The work interprets buffalo as a keystone species within the Yellowstone ecosystem, emphasizing their interconnected relationships with land, people, animals, and the spirit world. Buffalo, Deer, Bird celebrates the bonds between earth and sky, plants and animals, humans and spirits. Buffalo, deer, and reptiles inhabit the land below, while birds rise into the sky toward the Seven Sisters constellation, or Big Dipper, a symbol of the four seasons and the stages of life: birth, childhood, adulthood, and death. In the final season, silver and black animals transition into the spirit world.

What does the mural represent?

The mural’s imagery holds personal and cultural meaning for its creators. For Hitchcock, water birds reflect his Kiowa and Comanche upbringing. Arthur modeled red raptors after birds featured in the Draper Museum Raptor Experience, highlighting the Center’s ongoing conservation efforts.

From concept to installation, the mural took four months to complete with the help of studio assistants Penelope Johnson, Fifi Limbcomb, and Andie Almond. Each element was silk-screened, cut, and nailed by hand. When designing the layout, Hitchcock imagined the immersive soundscape of being at the center of a swarm of dragonflies, moths, songbirds, and raptors. Stretching forty-two feet, the mural incorporates three wall vitrines featuring Plains Indian Museum objects connected to song, dance, and seasonal life.

Cody Firearms Museum

The Cody Firearms Museum spotlight examines the tools used to hunt buffalo on the Great Plains and across the West, revealing a surprising range of firearms and motivations.

The selected objects demonstrate that buffalo were not hunted solely with what later became known as “buffalo guns.” Trade guns, flintlocks, and percussion rifles were used by both settlers and Native Americans well before the Civil War. Firearms commonly associated with buffalo hunting, such as the Sharps rifle and Springfield Trapdoor, were relatively new to the frontier by the time large-scale buffalo hunting peaked and declined in the early 1880s.

Other firearms, including the Evans and Winchester 1866, illustrate that many hunters prioritized practicality over power, often using calibers that would seem undersized by today’s standards. Utility, rather than specialization, guided many choices.

The exhibit also connects past and present by highlighting the role of modern hunting in conservation, including legislation like the Pittman–Robertson Act of 1937, which continues to fund wildlife conservation efforts today.

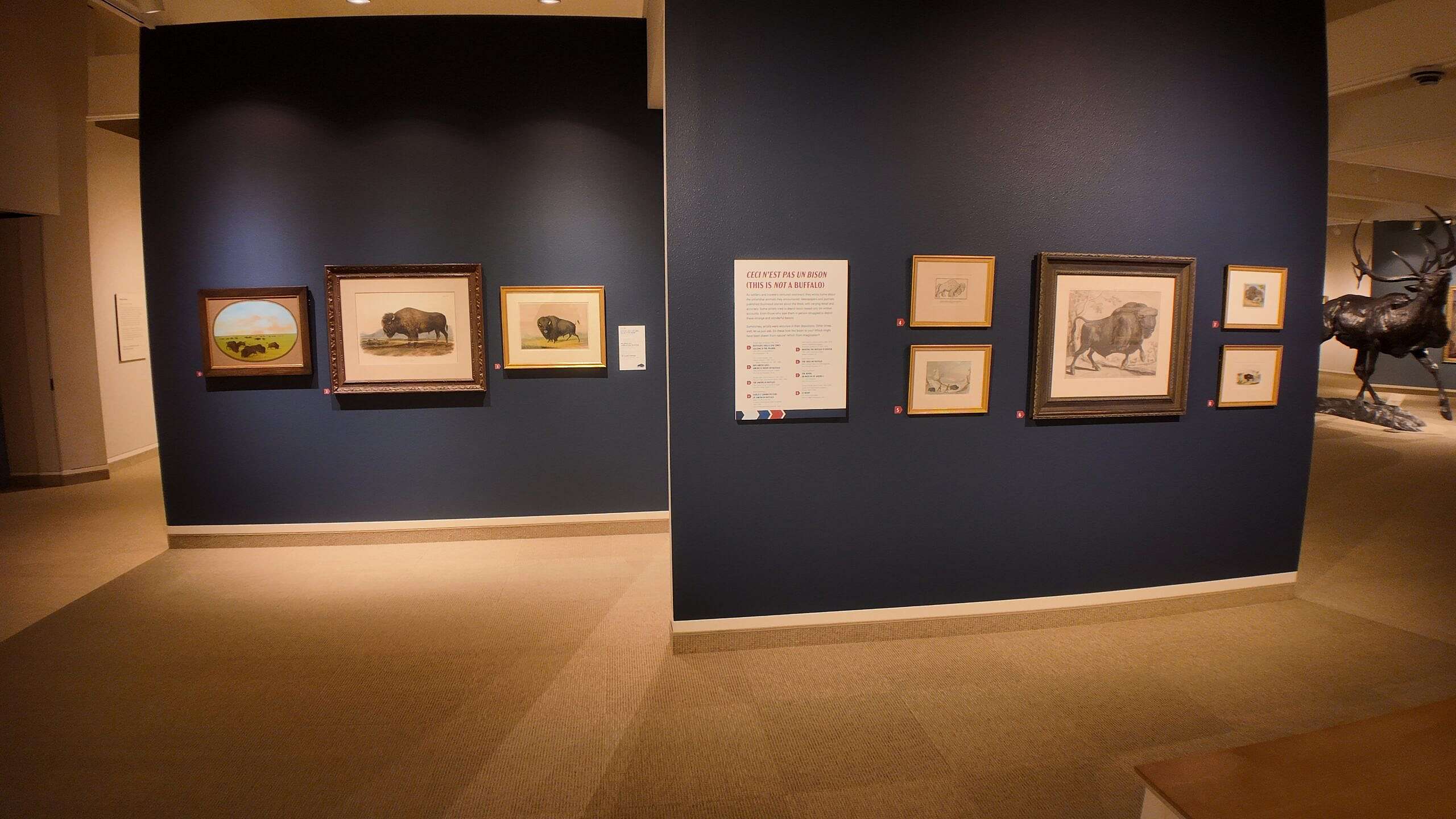

Whitney Western Art Museum

Bison in Art and Imagination brings together a special selection of artworks spanning five centuries, from the sixteenth century to the present. Paintings, prints, mixed media works, and sculpture offer varied interpretations of America’s national mammal, capturing its abundance, near extinction, revival, and enduring cultural meaning.

Early artworks humorously reveal artists’ struggles to accurately depict an animal few had seen firsthand. Historical masterworks include Albert Bierstadt’s evocative scenes of vanishing herds and William Jacob Hays’s vision of bison thriving in a sunlit West. Contemporary artists expand the conversation further. Julie Buffalohead (Páⁿka / Ponca) draws on Lakota prophecy, while Elaine Defibaugh incorporates familiar lyrics from “Home on the Range.”

Together, these works show the bison as sustenance, symbol, and spirit, viewed through many eyes and across generations.

Buffalo Bill Museum

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s identity is inseparable from that of the American bison. His global fame helped elevate the animal to national-symbol status, shaping how both Cody and the bison entered popular culture.

The Buffalo Bill Museum spotlight explores this intertwined legacy through objects and imagery that reveal the myth-making power surrounding both man and animal. Visitors can see “Lucretia Borgia,” the rifle that earned Cody his famous nickname, along with Wild West promotional materials, artwork celebrating his buffalo-hunting persona, and even a buffalo coat owned by Amelia Earhart.

McCracken Research Library

The Buffalo Nation spotlight in the Shiebler Gallery delves into the complex story of the American bison’s destruction in the late nineteenth century and the beginnings of conservation efforts. Photographs, postcards, and books trace this difficult history, examining William F. Cody’s evolution from buffalo hunter to conservation advocate and the role of bison in Wild West shows.

Visitors also encounter key figures in the conservation movement, including Chief Quanah Parker, Buffalo Jones, and William Hornaday.

Among the most significant objects on display is Swiss artist Karl Bodmer’s stunning portfolio Reise in Das Innere Nord-America in den Jahren 1832 bis 1834 (Travels in the Interior of North America in the Years 1832 to 1834). Between 1832 and 1834, Bodmer traveled more than 5,000 miles along the Missouri River with German explorer Prince Maximilian, documenting landscapes, wildlife, and Plains Indian nations. Bodmer produced over 400 field sketches and watercolors, while Maximilian kept a detailed journal. Together, their work offers an unparalleled record of Plains life in the 1830s. Selected images from the portfolio depict the bison’s central role in Mandan culture. This remarkable work is a generous gift from the Knobloch family and an exciting new addition to the library’s collection.

The library’s connection to bison storytelling continues into the present. In September 2021, the McCracken Research Library hosted Florentine Films during production of Ken Burns’s The American Buffalo. The Center of the West became one of the project’s top contributors of archival images and objects, with materials drawn from the McCracken, Plains Indian Museum, and Whitney Western Art Museum. Attentive viewers can spot more than a dozen Center objects in the final film and its companion book, Blood Memory.

Want to know more about Buffalo Nation?

The Buffalo Nation experience begins January 30, 2026, with six Spotlight Exhibitions presented across the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s museums and library. Each Spotlight offers a unique entry point into the buffalo’s story, through art, history, natural science, and fascinating museum collections.

On August 22, 2026, the primary exhibition opens to the public in the Duncan Special Exhibition Gallery, surrounding visitors with immersive environments and interactive experiences. To learn more about Buffalo Nation and all that is planned, head to Buffalo Nation – Buffalo Bill Center of the West.