Traveling With Charlie Russell

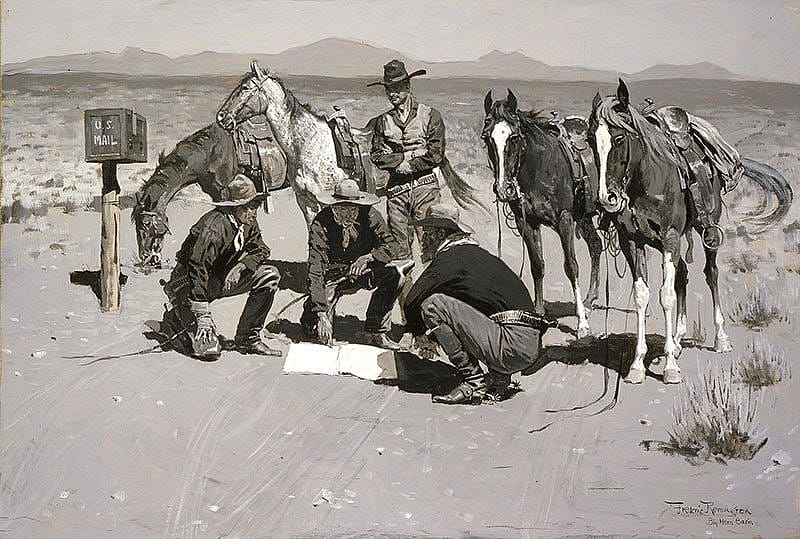

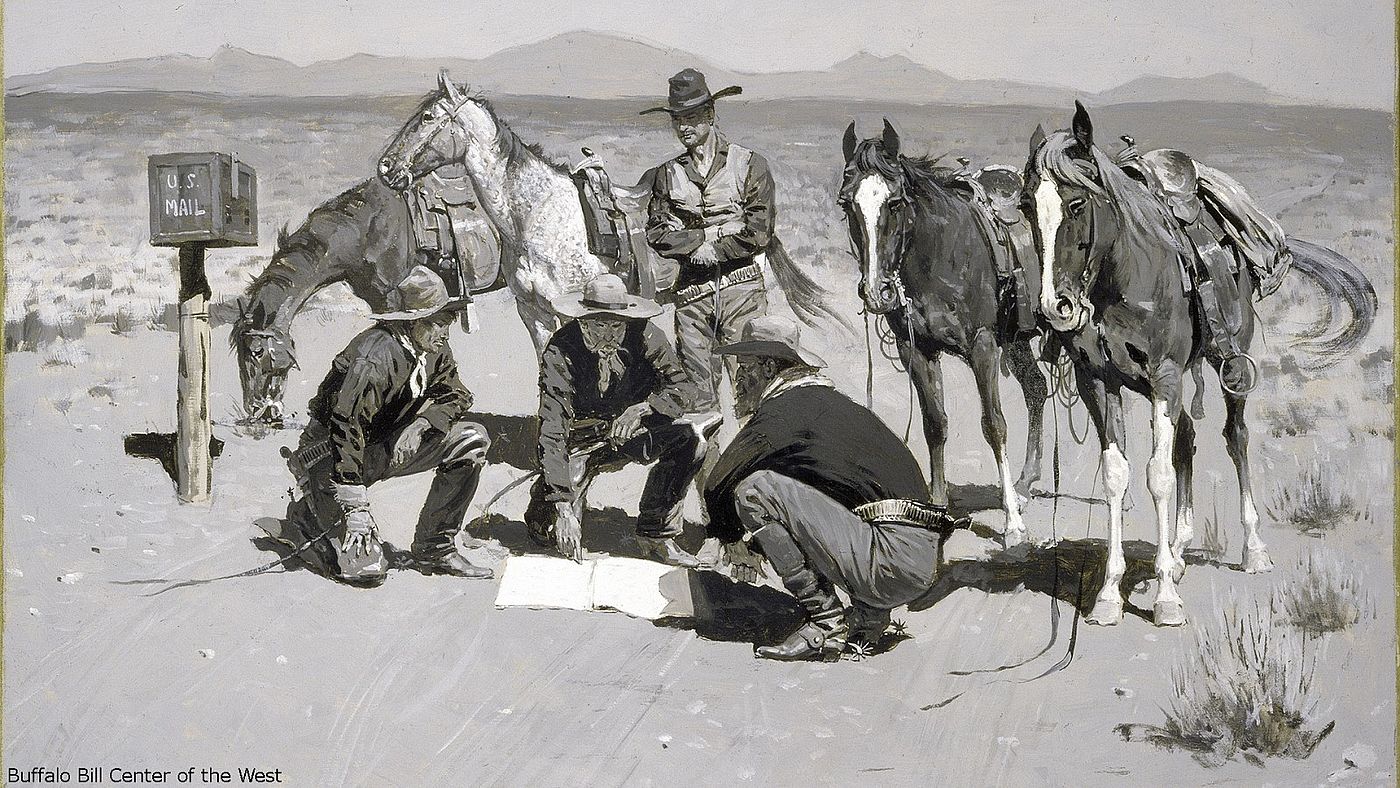

I dreamed the other night I was traveling with Charlie Russell. The first scene of my dream was suggestive of Frederic Remington’s painting A Post Office in the “Cow Country.” There were a group of us surrounding Charlie, out in the middle of nowhere at a crossroads. One of us handed him a catalogue raisonne of his work, which he autographed using a paintbrush and his “signature” buffalo skull. I thought that was pretty cool. Even better when Charlie reached for my copy and did the same thing.

Dream Charlie did not look like his portraits. Dream Charlie was short (no taller than me) and a bit overweight, clean shaven with short, reddish, strawberry blond hair. But this was Dreamland.

Flash to a bunkhouse at the Buffalo Springs Ranch, where I worked as a youth. Like Charlie, dream Buffalo Springs Ranch was not like the real thing. There were a few outbuildings, the likes of which are seen in paintings by Charlie or Frederic Remington—log structures faded, weathered, sound but showing age. The chinking was still in place. Charlie had a studio in one of those, and the Holtorf boys came and went as if Charlie were part of the family—which in the dream I suppose he was. He had some easels around. As I watched, he painted a picture—a stylized map of the West with trails and such marked out. It was remarkable how quickly he completed it.

He had objects about his studio as well: parfleches, bonnets, a rawhide box. I asked him if these were props he used in his paintings, like Remington, Sharp, or Koerner kept in their studios. Nope—just stuff he’d gathered.

I just finished a book, Big Sky by A.B. Guthrie. Published in 1947, it is the first in a series Guthrie wrote, the second of which, The Way West, won a Pulitzer Prize. A sub-theme of the book might be said to be that “wild country” is a relative term. Boone Caudill, the main character of the book, meets a fellow named Dick Summers, who becomes Boone’s mentor in learning the skills of a mountain man. In various places in the book, reminiscences first by Summers and later by Caudill describe the sensation of being the first person to see or experience a particular wild place, that the sensation could never be repeated, and that the country itself was changing. “It’s all sp’iled, I reckon, Dick,” Boone says in one of the final lines of the book.

Charlie Russell wrote a book of short stories, published after his death, called Trails Plowed Under–Stories of the Old West. Charlie arrived in Montana somewhat later than the period Guthrie wrote about. Still, he watched as the West changed, and his book—even the title—touches on the “taming” of the West.

My friend Den Barhaug grew up in Cody. He tells stories too, of how different the country of his youth was compared to today. His nephew, Larry Quick, used to drive a sheep herd right through town every year, when it was time to move to summer pasture in the high country. Those days are gone.

I could talk about my own house, how when we first moved into it we had an open view all the way to the chimney at the Heart Mountain Relocation Camp. We can still see the chimney, but now there are a bunch of houses in between.

Soylent Green happened to be on Turner Classic Movies the other night. I hadn’t seen it in many years so we watched it. It was made in 1973. I didn’t remember that as early as 1973 someone was already talking about the greenhouse effect. But there it was.

“It’s sp’iled, I reckon, Dick.”

Written By

Phil Anthony

Phil Anthony is the Operating Engineer at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. He has been in the HVAC-R service industry for over 30 years (fifteen of them at the Center.) Phil holds journeyman certificates through the City and County of Denver as a steamfitter and a refrigeration technician, and a low-voltage electrical technician’s license with the state of Wyoming. An artist, poet, musician (sort of,) and avid outdoorsman, Phil has been called "a true renaissance man."