On Mechanical System Shutdown in Collection Storage Areas

Our chief conservator, Beverly Perkins, returned this week from the 42nd annual conference of the American Institute for Conservation held this year in San Francisco. She thought I might be interested in some of the papers presented at this meeting, so she gave me her abstract book to review. She was right—one topic in particular piqued my interest. The presentation was titled “Research on Mechanical System Shutdown in Collection Storage Areas,” and it caught my attention because it discusses a practice I first began implementing eleven years ago.

I’m frankly dismayed that the museum community is only now investigating the potential energy savings benefit of a formula that the commercial building community has been implementing for time immemorial.

The scientific method, as I was taught it, is as follows:

- Observation (you see something you’re curious about)

- Hypothesis (you present an explanation for what it was you observed)

- Experimentation (you devise ways to test your hypothesis, to see if it holds up)

- Theory (rigorous experimentation has perhaps caused you to modify your original hypothesis, but your idea has reached the point that every experiment you or your peers has performed has only reinforced the truth of your explanation—it is the accepted explanation for your initial observation)

- Law (if you’re lucky, an unassailable mathematical equation can be formulated to prove your theory)

I bring this up because this is precisely how I discovered I could save the museum a pile of money, and is also, I’m sure, the method by which the authors of the aforementioned paper came to their conclusions.

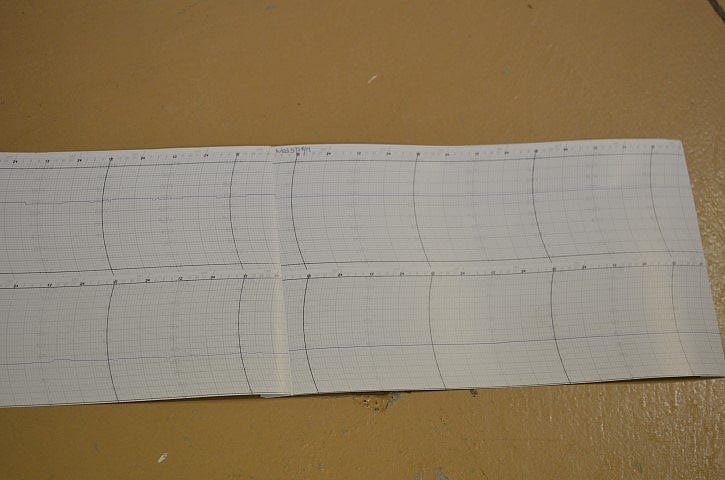

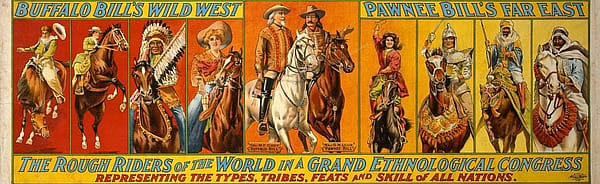

Observation: Early in my employment here, I was forced into an extended shutdown of the Center’s Buffalo Bill Museum section’s HVAC unit. It had a significant vibration which was causing bearing failure. To correct it, I needed to remove the blower wheels and send them to Billings for balancing. The fan was off for days. Looking at the recording hygrothermograph chart (time period one week) for that museum after the work was complete, I saw no significant difference in either temperature or humidity readings between the periods the fan was on and when it was out of service.

Hypothesis: In 2002, after completion of the Draper Natural History Museum, our utility bills skyrocketed. My supervisor asked me to see what I could do to reduce energy consumption, and I related to him my previous observations of the Buffalo Bill Museum, postulating that if I could cycle the mechanical equipment off during unoccupied hours, we could perhaps save some money without putting our collections at risk.

Experimentation: I devised programming for our computerized control systems which would turn off our mechanical systems during the night, but would turn them back on if our indoor environment exceeded high or low temperature, and humidity limits established through discussions with our conservation consultant (Beverly as it happens, but she wasn’t a museum employee at the time.)

This was not a fast process. We have a lot of mechanical equipment, after all, and parts of our building react to shutdowns far differently than others. My hypothesis had to be revised, in that two of our air handlers (to this day) never turn off. The rate of cycling (on-off-on-off) is just too great, and with one unit at least, the concept is further complicated by the fact that one area of the building supplied by that fan is never, ever, completely unoccupied. We also found out the hard way that while good energy savings could be achieved in winter months with the fans off at night, resulting condensation in our soffits was causing the stucco to fall off! Program logic had to be revised—and energy savings sacrificed—to prevent this.

Nevertheless, by 2009 electrical consumption was reduced by 27 percent, and natural gas consumption reduced by 31 percent relative to our peak consumption year of 2002, with minimal deflection in our indoor climate.

My advice to museum operators out there is: don’t be afraid to experiment! Energy savings can be achieved without detriment to your collections! As for me, I had no idea I could get grant money for doing this kind of work. If you, dear reader, are associated with a grant funding institution with money to be spent on projects such as this, I am not out of ideas yet!

Written By

Phil Anthony

Phil Anthony is the Operating Engineer at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. He has been in the HVAC-R service industry for over 30 years (fifteen of them at the Center.) Phil holds journeyman certificates through the City and County of Denver as a steamfitter and a refrigeration technician, and a low-voltage electrical technician’s license with the state of Wyoming. An artist, poet, musician (sort of,) and avid outdoorsman, Phil has been called "a true renaissance man."