Buffalo Bill and His Donkey – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2009

Buffalo Bill and His Donkey

By Sandra K. Sagala

From Cleveland to Louisville to New York, critics seemed always ready to comment on Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Sandy Sagala has studied numerous accounts of the show, and for this story, discovered a star, of sorts: Jerry the Donkey.

Before he organized his Wild West show, William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody traveled the country as an actor playing in frontier melodramas. After only a few years, he adopted the role of educator, as well as actor. As such, he realized the artificiality of the plays and began to incorporate increasingly realistic western effects. Because animals were an integral aspect of the West, Cody’s decision to feature them in his dramas was significant.

Fellow scouts of the plains and later professional acting troupes accompanied him, playing secondary roles. For the most part, critics wrote flattering reviews. However, the occasional negative assessment should surprise no one as Cody was still learning the craft, and once in a while, his performance was less than sterling. The plays, too, particularly the early ones by Ned Buntline, were over-the-top melodramas. Ignorant of theatrical techniques, Cody affected a natural posture and, despite the criticisms a bad play might invoke, his presence was a showstopper.

For several months, Cody partnered with Jack Crawford, a military guide and “poet scout.” The two fought over many things, not the least of which was a plan to bring horses onstage. When they performed in San Francisco, the June 9, 1877, edition of the Chronicle reported that Cody and Crawford introduced “two very frightened horses” on stage which eventually settled down and performed admirably. Later, in an August 7, 1877, letter to Crawford (after he’d previously incurred Crawford’s wrath over a shooting accident), Cody insisted “it was not my fault as I never wanted to put the horses on stage. “

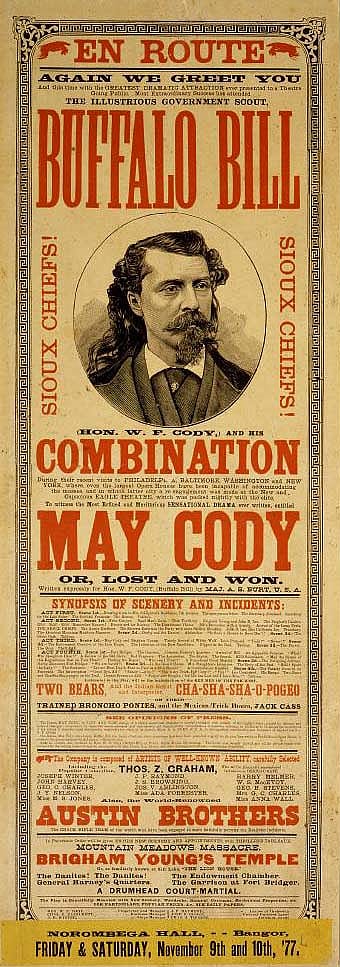

Horses may not have worked out for various reasons, but in September 1877, in a play by Andrew S. Burt titled May Cody, or Lost and Won, Cody introduced a “wise little donkey.” Donkeys better served the purpose because, though they were generally more stubborn, once trained, they were more able to climb the steep stairs leading to the stage.

Before the Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, performance, Cody had unfortunately imbibed rather freely and his usually sober act was not quite so. A critic with the local Record of the Times wrote on March 27, 1878, that he hoped Cody would take better care of himself and not spoil any more evenings. In this instance, the donkey received one of his own first positive reviews when the critic added, “The donkey’s acting was a redeeming feature of the play–and he was sober, too.”

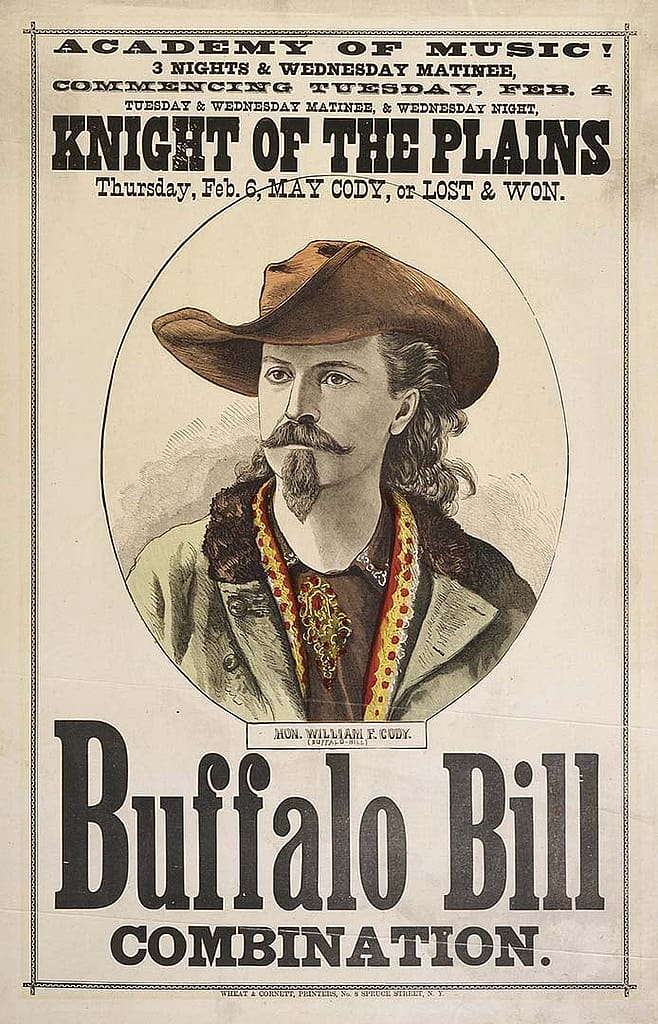

The next year, Cody’s play was a Prentiss Ingraham work titled Knight of the Plains, or Buffalo Bill’s Best Trail. The little gray animal was again in evidence, this time with Buttermilk, an African American servant character. Buttermilk played scenes with an Indian and with a Jew, but those with the donkey drew the most applause according to the Fort Wayne, Indiana, Sentinel of October 16, 1879.

For the 1879 season, Knight of the Plains predominated with an occasional performance of May Cody. Harry Irving played Buttermilk and cavorted with the donkey while Charles Wilson took his turn as Darby McCune. One critic in Cleveland thought both men created “considerable amusement, and they are continually getting out of one scrape only to fall into another.” In Louisville, a reviewer judged Knight of the Plains “nothing particular” as drama, adding that the acting, “although some of it is very effective, with the spectators, is not noteworthy.” Nevertheless, “the intelligent-looking and handsome donkey” (named “Jerry” in the program) “acted his part capitally, making a deserved hit.”

Cody’s last, most expensive, and longest-playing drama was Prairie Waif: A Story of the Far West. John A. Stevens wrote it especially for the 1880 season, and it continued the tradition of including a stock humorous character. German comedians Jule Keen and Bonnie Runnels alternated in the role of Hans. Jerry took the role of Jack Cass, the donkey. Although the Prairie Waif continued throughout the 1881 season, the cast listing excluded the donkey. Jerry was along, though, and causing trouble, as the following story from the Chicago Tribune, dated September 5, 1881, illustrates:

While Cody checked in at the Tremont Hotel, Jerry was to room in a basement stall at Beardsley’s livery stable. Around 10 p.m., the “gray-haired and demure-looking specimen of the long-eared tribe, “despite his supper of oats and fresh water, refused to settle down for the night. Instead, he tore up the stairs “with the speed of a locomotive, “ears thrown back and eyes glaring. The stablemen at first thought the sight great fun. One bet that if his halter had not slipped off, Jerry would have “dragged the basement up-stairs with him.”

A boy jumped on his back, but the donkey dashed back down the stairs and brushed off his passenger by rubbing against a post. The stablemen rushed after him, so Jerry kicked up his heels, knocked over two of them, then “waltzed” back up. Jim Killoan and another man managed to drive him down and hold his head, but the animal bit Killoan’s left arm and held it. He screamed “bloody murder” and grabbed with his right hand to pull the donkey’s ears, to no avail.

At this, every other man armed himself with a club and beat the animal, but Jerry’s kicks precluded any proximity. He suddenly opened his mouth, letting loose Killoan’s arm, and jumped for Pat Houlihan, the night-watchman. Jerry dragged him “in the most violent manner” across the floor. The men seized heavier clubs and a rope with a slip noose. Observing the furious activity, Jerry “inadvertently opened his mouth to smile,” and Houlihan removed his arm. Someone was finally able to slip the noose over Jerry’s head and pulled it so tightly that the poor animal’s tongue protruded. Dr. C.S. Eldridge ascertained that Killoan’s and Houlihan’s arms were critically lacerated. Between the loss of blood and the shock, the two men were barely able to stand.

The Tribune reporter did not mention what, if any, damages the stable owner required Cody to pay; neither did the calamity seem to interfere with Jerry’s future acting career. He—or perhaps a docile, more obedient understudy—remained a sensation even a year later while Cody and the others came in for censure. A Canton, Ohio, critic thought the production of 20 Days or Buffalo Bill’s Pledge, “not worthy of any favorable mention” and wondered in print “[w]hy people hunger for this class of amusement…. The only good feature of the show was ‘Jerry,’ the trick donkey, but as he would fail to appreciate a good notice we forbear.”

The incidents with Jerry were good learning experiences for Cody. In only a few years, he would travel with many hundreds of animals in his Wild West show. Their contributions were almost always satisfactory too.

Sandra K. Sagala has written Buffalo Bill, Actor: A Chronicle of Cody’s Theatrical Career and has co-authored Alias Smith and Jones: The Story of Two Pretty Good Bad Men (Bear Manor Media 2005). In May 2008, the University of New Mexico Press published her book, Buffalo Bill On Stage. She did much of her research about Buffalo Bill through a Garlow Fellowship at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, as well as a 2008 research fellowship from the Center. Her article comparing Buffalo Bill with Mark Twain was serialized in Points West‘s winter 2005 through fall 2006 issues; the online version of the series begins here. In the spring 2008 issue, she wrote about firearms mishaps in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West; the online version is here. The Fall/Winter 2018 issue features Sagala’s article Nate Salsbury’s Black America: Its Origins and Programs. Sagala lives in Erie, Pennsylvania.

Post 225

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.