Buffalo Bill and La Rana nel Wild West, conclusion – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2015

A Leap But Not a Stretch: Buffalo Bill and La Rana nel Wild West, conclusion

By Mary Robinson & Robert W. Rydell

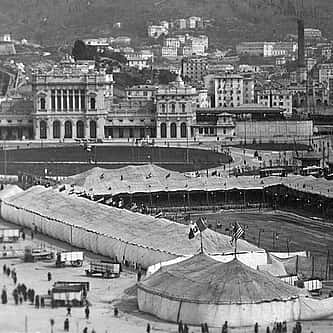

One of the Center’s most striking and original posters shows Buffalo Bill astride a bucking bullfrog. In the last issue of Points West, Mary Robinson and Robert Rydell shared how their interest in the poster led to a story with many more facets than they bargained for: politics, economics, and social change.

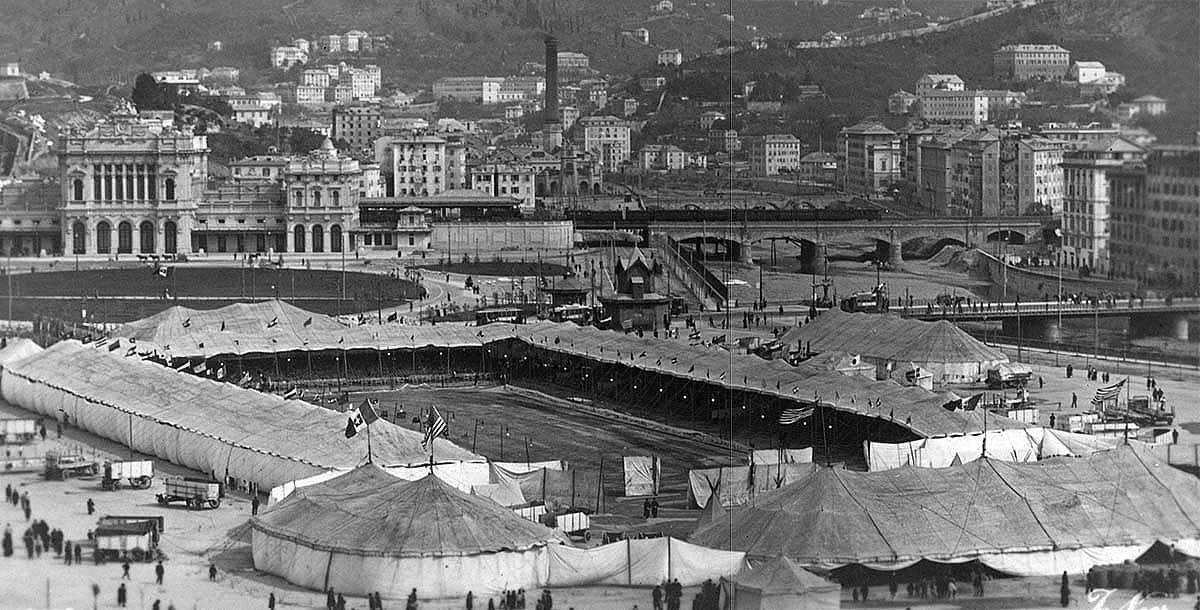

La Rana (“the frog”), the Bologna, Italy, magazine to which the poster refers, latched on to the appearance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Italy as a platform for its current events commentary.

In the conclusion of “A leap, but not a stretch,” the authors discuss further the social and political problems in Italy at the turn of the twentieth century, beginning with a poem published in a 1906 issue of La Rana.

The long poem, “Buffalo Bill’s Arrival” (from the March 30–31, 1906, issue of La Rana) seems to hail Cody as a conquering hero, opening with a Homeric echo, “I sing of redskins and the Captain.”

For the last twenty years, the celebrated Cody has visited

The civil barbarians and showed them

How uncivil barbarians [meaning the Indians] plunder using arms and battles;

While, with yellow gloves [white collar crime?], in some banks

Our people commit robbery without being noticed.

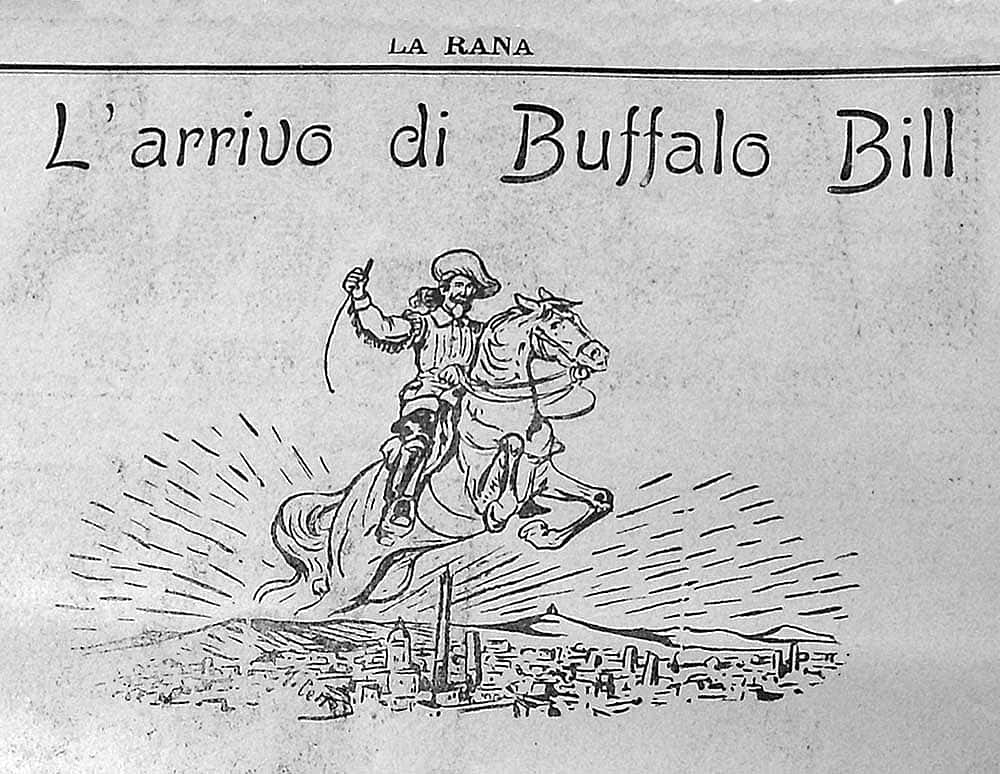

In this poem, the crowd meeting Cody’s train is portrayed as restless, hungry, and, potentially, even violent. Buffalo Bill himself, described as “stunned,” appears unprepared for the scene.

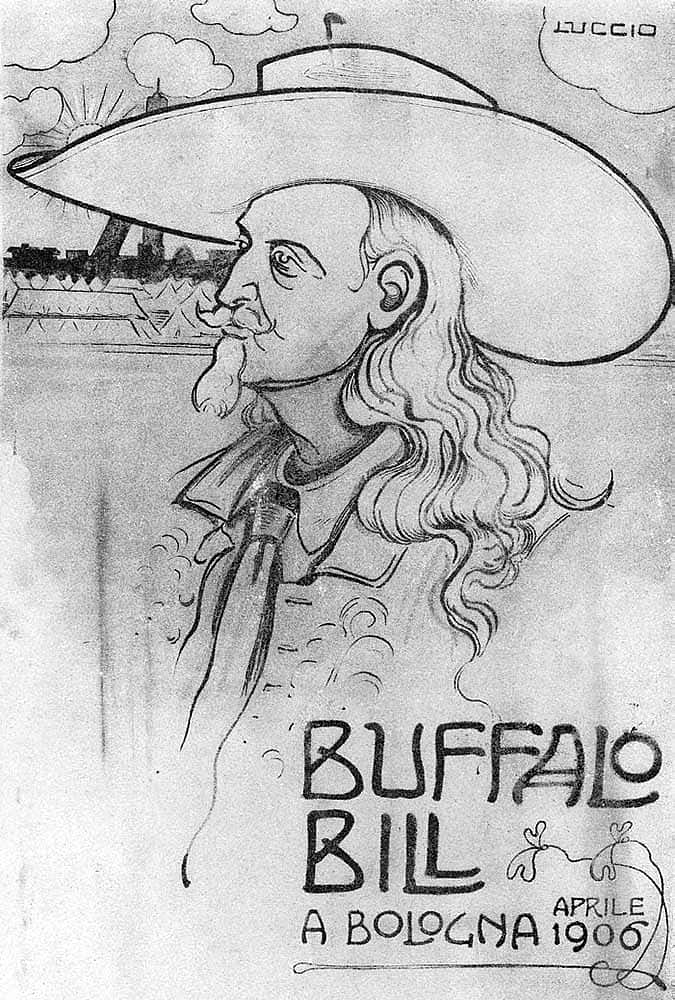

Cody’s signature hat also becomes a focus in the poem. The Italian image of Buffalo Bill often portrays him in a musketeer’s hat worthy of Cyrano de Bergerac. In this instance, however, the large hat reinforces the theme of banditry. La Rana‘s editors clearly use the Wild West’s arrival to call attention to civil strife and corruption in Italian society.

On Church and State

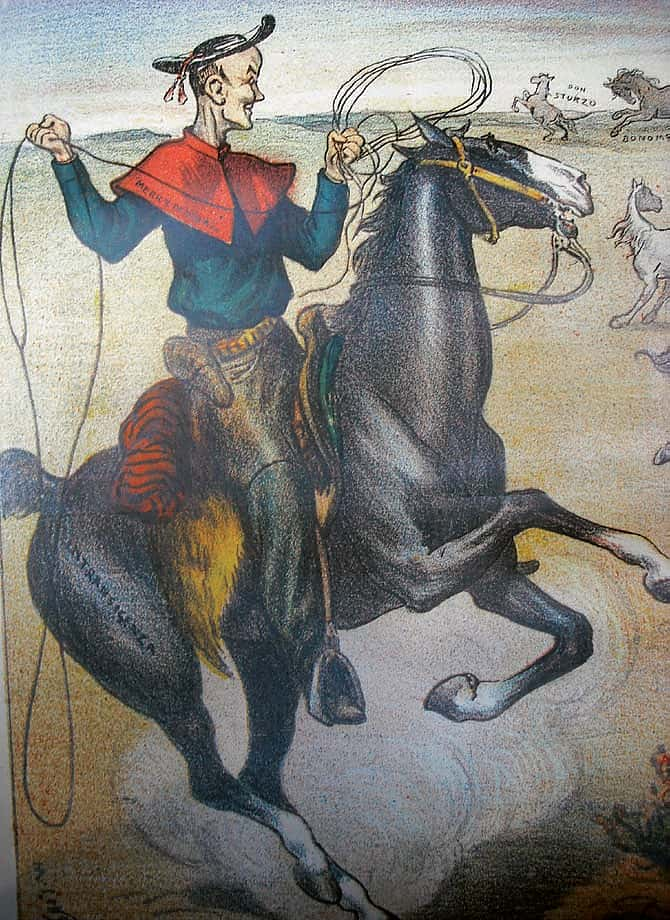

Between the magazine’s covers, both domestic and international issues—and the Wild West—get recast into commentary. In another gem of graphic satire, La Rana continues its tradition of anti-clericalism by lampooning one of the most powerful figures in the Vatican, Cardinal Merry del Val. The cardinal was one of Pope Pius IX’s leading anti-modernist crusaders and soon-to-be Vatican Secretary of State. He appears in a cartoon headlined “Merry del Val in the Wild West,” riding a horse named “Intransigence” as he tries to lasso his clerical critics and bring them into line. The prancing wild horses identified as Don Murri and Don Sturzo, and others, are associated with liberal thinking within the church.

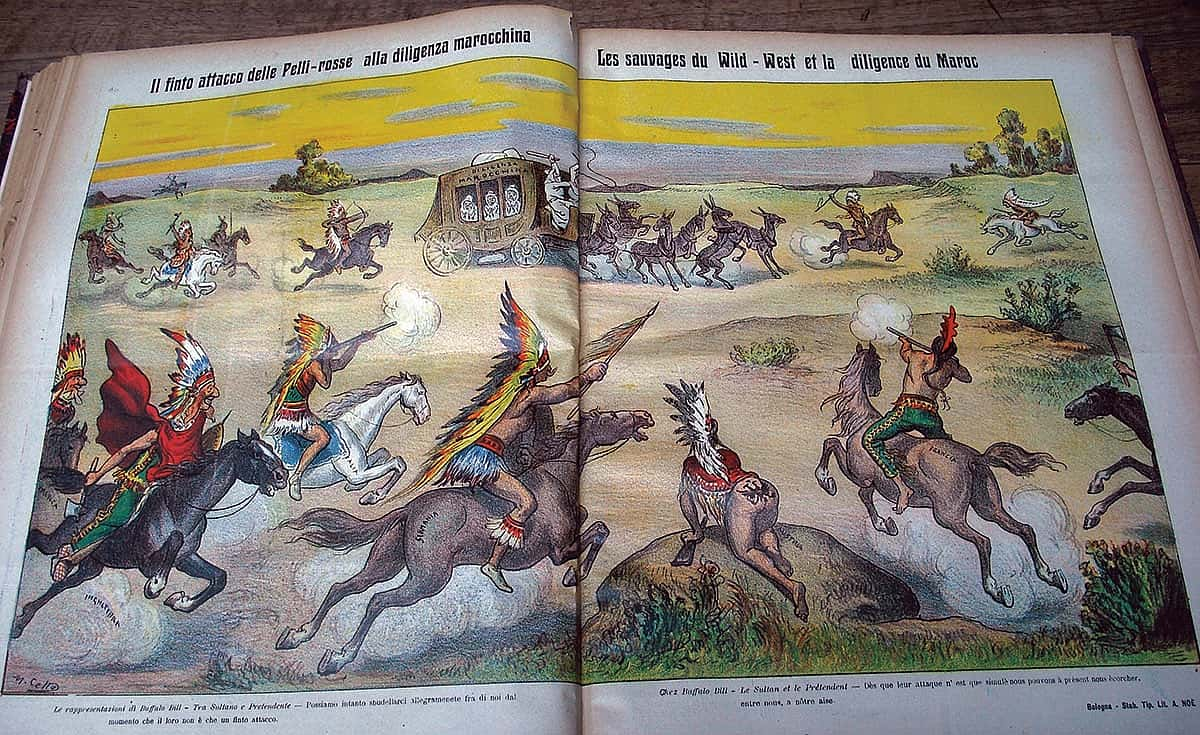

Always attentive to current events, La Rana connected its readers to the Algeciras Conference (January 16–April 7, 1906) that brought a temporary end to the First Moroccan Crisis just as Cody was arriving in Bologna. Generally considered one of the prequels to the First World War, the crisis in Morocco centered on German efforts to block French intentions to colonize the as-yet-independent North African country. With the Algeciras Conference closing and the Wild West set to open, La Rana‘s cartoonist drew on the repertoire of the show to explain what had just transpired.

The satirist portrayed various European nations and America as Indians in pursuit of a stagecoach filled with Moroccans. The Ottoman Sultan drives the coach and cracks a whip to fend off the Pretender to his throne, seated beside him brandishing a sword. A caption below reads, “With Buffalo Bill: the Sultan and the Pretender. Since they are only simulating a fight, we can at present skin ourselves at our leisure.” The Indian representing Austria seems especially treacherous, as he crawls over a rock showing the Hapsburg coat-of-arms tattooed on his backside.

There are many layers and jokes here. We get the drift, we think, and admire the energy and creative zeal of these Italian satirists. La Rana is indeed a colorful feast for the eye with a provocative message designed to afflict the comfortable.

Author and historian Louis Warren has argued that Buffalo Bill’s Wild West drew huge crowds of Europeans because of the way it spoke to their desires and anxieties. Instability was but one overriding anxiety in Italian society, underscored by the replacement of Sidney Sonnino and his government the very next month—in May of 1906. During the first decade of the twentieth century, Italy changed prime minister ten times. Through the lens of La Rana and the metaphors of the Wild West, we glimpse serious social dislocation, internal strife, political chaos, failed leadership, and a frustrated populace.

In hindsight, we recognize that these conflicts portend developments much darker than La Rana‘s editors, for all their savvy hilarity, could have imagined. Even today, the illustrations in La Rana and the story of Buffalo Bill in Bologna serve as useful reminders about how, when it comes to the Wild West, circuits of meaning flow across spaces, cultures, and times.

And how did the Wild West view the Italian strife?

“All kinds of bad things were predicted for us in Italy, and many of us had it down as a land of anarchists, with bombs and stilettos, but we found the people the most peaceable and more subject to police control than any country we visited outside of England.” —Charles Eldridge Griffin, Four Years in Europe with Buffalo Bill.

“…these [Italian] people are so d—— crazy wild to see something for nothing. They run all over us. I am going to kiss the first New York policeman I see.” —William F. Cody, in a letter to James Bailey dated March 25, 1906, from Rome.

Another leap: The frog finds its way to America

In the process of teasing out the fascinating resonances of La Rana Nel Wild West, we uncovered another story that brought the journey full circle. According to collection files in the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s registrar’s office, the original owner and subsequent donor of the “Cody and the Frog” poster to the Buffalo Bill Museum was Oliver Malcolm Wallop who a sent a letter dated April 22, 1959, to Mary Jester Allen, the first director of the museum, from Big Horn in Sheridan County, Wyoming. In the letter, he reveals that the poster appeared among family papers, and he sketches a possible scenario for how it came into their possession.

It seems that his father, Oliver Henry Wallop, had traveled to the continent shortly after the turn of the century. He’d suffered a serious illness in England and recuperated in Biarritz on the French coast in 1902. He may have acquired the poster at that time.

Like us, Oliver Malcom Wallop’s letter asks Mary Jester Allen to explain one thing: Why is Buffalo Bill riding a frog?!

Many readers know that the Wallop family in Big Horn, Wyoming, has strong ties to England. Oliver Henry Wallop would become the eighth Earl of Portsmouth. He had immigrated to America as a younger son who would not expect to inherit the family title. Consequently, in 1883, at the age of twenty-two, he purchased the Canyon Ranch in Big Horn, Wyoming. There he remained as a rancher until death in the family in England caused the title to descend to him. In 1925, he returned to England to become the Earl of Portsmouth.

His son, Oliver Malcolm Wallop, donor of the poster, remained in Wyoming, and Oliver Malcolm’s daughter, Jean, who was born and grew up in Wyoming, married the man who would become the seventh Earl of Carnarvon and owner of Highclere Castle. Jean, now the Dowager Countess of Carnarvon, lives near Highclere, but often returns to Wyoming. Her brother, Malcolm, a U.S. Senator from Wyoming (1977–1995), died in 2011.

The Wyoming Wallops visit their cousins and enjoy watching public television’s Downton Abbey—filmed at Highclere—with the rest of America.

The search for La Rana touches on this interesting Wyoming connection to England and the popular series about the English upper class adjusting to social change during the first decades of the twentieth century. This is precisely the tumultuous time period in Italy that produced the satiric La Rana. While Oliver Malcolm Wallop dated La Rana Nel Wild West to the time of his father’s trip to France, we know that the poster’s appearance coincided with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West tour of Italy in the spring of 1906. Rest assured, we’ll change the incorrect date of 1902 on the poster label.

Mary Robinson is Housel Director of the Center’s McCracken Research Library. Robert Rydell is Michael P. Malone Professor of History at Montana State University in Bozeman, Montana.

Authors’ Note: University of Wyoming Professor Renee Laegreid’s “Finding the American West in Twentieth-Century Italy,” which appeared in Western Historical Quarterly, winter 2014, sheds additional light on the Wild West in Italy more generally.

Post 253

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.