The Man Who Was Scalped

I was lucky enough to meet Gordon Barrows. He danced into my office one day. I’m not sure what the occasion was. It may have been to give the library a copy of his autobiography, but I don’t really remember. He told me about growing up on a ranch, herding cows in a place called Natural Corral. A spring comes out of the ground there. In the 1930s Gordon and his Dad stocked it with trout. You can still see them there, fat, lazy, swimming in comfort, far from the outside world. This may have been the trout’s deal, but it was not Gordon’s. He was far-flung. He served as a medic in World War II, attended international relations school, and spent two years as professional spearfisherman in Mallorca. Then he founded the World Petroleum Report. This blasted him into the upper reaches of the petroleum industry, and society in general. But he never forgot the spring. He told me about it, how the water was crystal clear and good to drink, coming up out of the Wyoming desert.

But I am not here today to talk about pure things. Gordon met a man who was scalped. The story of a man who escaped death begins with – death. Riding cowboy one day, Gordon came upon 19 calves that had been killed by a marauding grizzly. Let him tell the story:

When we rode up the cows were a bloody sight. Calves lay everywhere – they had tried to escape … some of them did, but 19 was a big loss. This was no job for us. Stopping a grizzly as big and mean as this one was too dangerous. Professional help was needed. Enter the Government Trapper.

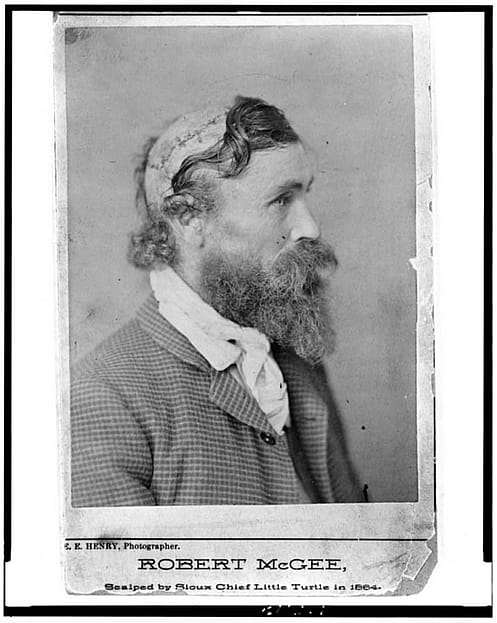

My father sent word to summon the government trapper, a professional paid by the US Government to trap predators. I, at ten years old, had exaggerated ideas about the trapper. The very concept of a man who spent his life outside tracking down predators made him seem like the biggest predator of all. I awaited someone who looked like Daniel Boone, and I was not disappointed. When he arrived he was everything I had envisioned, and then some. Grizzled, bearded and about 60 years old, he had one feature that never ceased to fascinate me as a young lad – he had been scalped by the Indians.

The scalping must have occurred in the late 1800s. He was vague about dates and, in fact, never wanted to talk about much about anything except predators and traps. The story was that he and his partner were coming over the Beartooth Mountains and camped for an evening. He woke up during the night to see an Indian standing over his partner. He grabbed his rifle to shoot, but never got off a shot – instead he was seized by Indians who had sneaked in behind him. He and his partner were tied up. The Indians began a long powwow. It lasted the night, with the Indians dancing and singing.

The unfortunate two watched – their legs and hands tied behind them. When dawn came the Indians heated water by dropping hot stones in water contained in a tub made of buffalo skin. They cut the two partners feet loose and led them up a hill, singing and screaming. As they went up the hill a strange odor began to manifest itself. Somehow the trapper knew it was a snake den, and so it was. The snakes were lethargic, but the hot water dumped on them soon brought them out and made them a writhing angry mass. At this point they untied his partner and threw him into the pit.

The trapper decided he would sooner die than suffer the enormous cruelty of what his partner was going through. He began to run, his hands still tied. For a few seconds the Indians did not realize he had broken away, so hypnotized were they by the grisly scene that was playing itself out before them. He had covered 100 yards when a loud “WHOOP!” told him they had seen his escape. A young warrior dashed out after him, tomahawk shining in the dawn sun. He caught up to the trapper, his tomahawk descended and the trapper died. So they thought. He woke up many hours later, hands till tied, scalped. Somehow he got free, took an old kerchief and put it over his scalped head to keep off the sun and flies. He walked to Cody, Wyoming. There he recovered, but his scalp was gone. All that remained was scar tissue. It looked like whitecaps on the ocean, though he never took his hat off in public. I saw it once when I burst in on him while he was staying at our Black Shack, a bunkhouse covered with black tar paper for cowboys.

The trapper disappeared into the predawn every day, working on the grizzly problem. He carried enormous steel traps, three feet wide and heavy, up into the narrow canyon that led into the Natural Corral, along with log chains so heavy I could only lift a few links. The traps were set, waiting. And one night it happened. Sometime in the night the trap closed on the great bear’s paw. He let out a roar of rage that shook the canyon. Even the birds stopped singing. In the hush I peeked out the window at the black shack and saw a shadow move. The trapper was on his way to meet the bear.

Quietly I slipped out of bed, grabbed my .22 rifle and followed in the darkness, unseen. Dawn was lighting hills when I came up the trail, crossed Paint Creek that came out of the Corral and headed up. It was only a moment later that I heard the clink of log chain, looked up to see the grizzly’s furious red eyes. He had doubled back on the trail to catch whoever did this to him. And I was it. He came so fast I never had a chance to raise my .22 – not that it would have made any difference. He hit the end of the long chain attached to the trap three feet in front of my face. Words cannot convey the feeling of terror and doom. They came simultaneously with the boom of the trapper’s gun. He knew what the bear would do; he had circled and come from above. Again and again he shot the bear until that great head finally fell. Then without a word he led me back to the ranch. He left the next day after collecting his grizzly bounty.

I never saw him again.

Barrows, Gordon H. 2012. Sagebrush dancing. Volume I. New York: Peregrine Potter Press. Pages 153-160.

Did ten-year-old Gordon really face off with a grizzly bear armed with a .22? Cody, Wyoming was not founded until 1896, long after Native American depredations on whites in the area had ceased. It is unlikely the government trapper had a Cody, Wyoming, to walk to at the time. Since coming to the Buffalo Bill Center I have been conducting oral history interviews. People say to me, “[So and so] will yank your chain.”

“So what?” is my response. I point to the words emblazoned on the wall of our reading room. “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Gordon died not long after I met him. He came in my office like an apparition and left just as quickly. I was surprised to hear he had passed away. To me it looked like he could have gone on forever.

Written By

Eric Rossborough

Eric has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the McCracken Research Library. Eric comes here from Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.