Philip R. Goodwin, or, A Child Prodigy Runs Afoul of the 20th Century

It was December, and I had just walked into the shelving room of the Madison, Wisconsin, Public Library. My job. The room was full of blue rubber tubs on wheels, and these tubs were full of books.

My boss, Mark Penner, looked at me with a sardonic grin. “Take what you want,” he said.

Public libraries are different from academic libraries or special libraries like the McCracken in that public libraries exist to cater to the public, and every few years, they will go through and weed things that haven’t been circulating lately.

I go through these bins, reaching in with my whole upper body, and come out with a major haul. I had to get rid of most of these books when I came out here, but at any rate, one of the books I pulled that day, Great Sporting Posters of the Golden Age, was put to immediate use. I had a plan. I went home and cut out the pictures I liked with an exacto knife, and threw the book away. The wall in the room of the student tenancy I lived in had these holes in it, where a shelf had been. I was too lazy to fill them in with putty or paint over them, and so I pasted these pictures of guys hunting and fishing in a row, over the holes.

My roommate, an art student named Kim Benson, came home about that time and I proudly showed her my home improvement.

Kim moved her head slightly forward, pulls it back and then tucks her chin in and looks at these pictures like they are a dead skunk or something.

I say, “Don’t you like this? This is some real art.”

And she says, “Uh, right.”

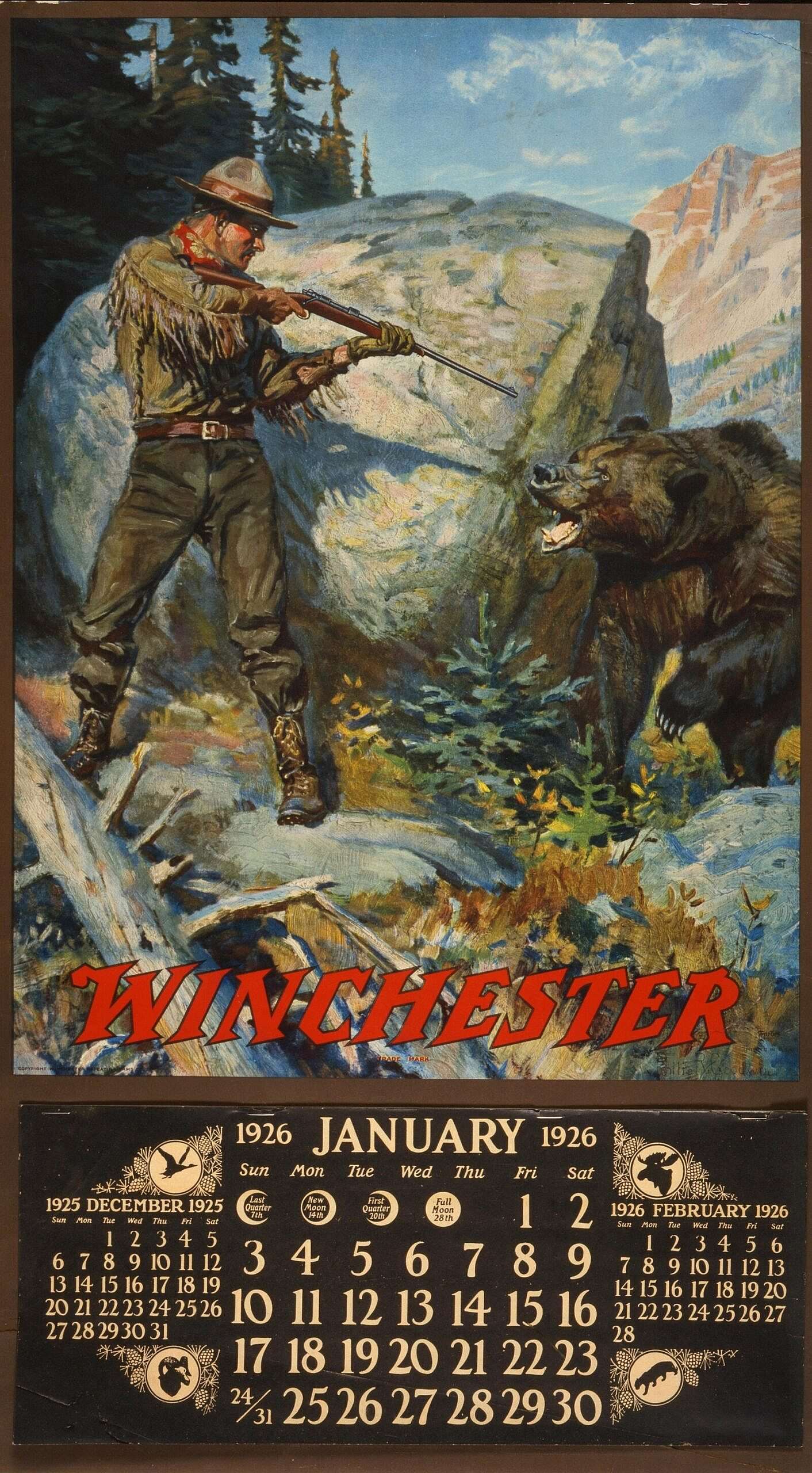

I was basically needling Kim. She paints postmodern art. And I thought she would hate this work she would likely deem to be formulaic and unchallenging. But I liked it. The weird thing is that, after I had cut out the pictures I liked the best, I realized they were all by the same guy, Philip R. Goodwin. Then I came out here and find I’ve come to work in a library that owns this guy’s letters, and in a museum that has his original art and notebooks.

The one thing I can say about Philip Goodwin is that he was born at the right time. Born in 1881, he was a child prodigy who sold his first illustration at the age of eleven. Focused on animals, he got his first big break when the “Father of American Illustration,” Howard Pyle, took him on.

Pyle combined his own illustration work with teaching at Drexel University, but he chafed at the academic confines, so he set up own school, taking on his own handpicked students. Pyle produced a whole flock of great illustrators; many of the artists of what was called the Golden Age of American Illustration learned under him: his students included N. C. Wyeth, Frank Schoonover, Jessie Willcox Smith, Maxfield Parrish, W. H. D. Koerner, Violet Oakley, and others.

While Wyeth and Schoonover seemed focused on the male figure, Goodwin liked animals. His early work shows an almost psychic empathy, as if he is inhabiting them himself. After graduation, Philip sold a couple of pictures to The Saturday Evening Post, and the art editor, Thornton Hardy, thought enough of Goodwin that when he received a book manuscript in 1903 called The Wolf, he suggested to young Goodwin that he might be a perfect match. It wouldn’t pay well, however, for the author was an unknown.

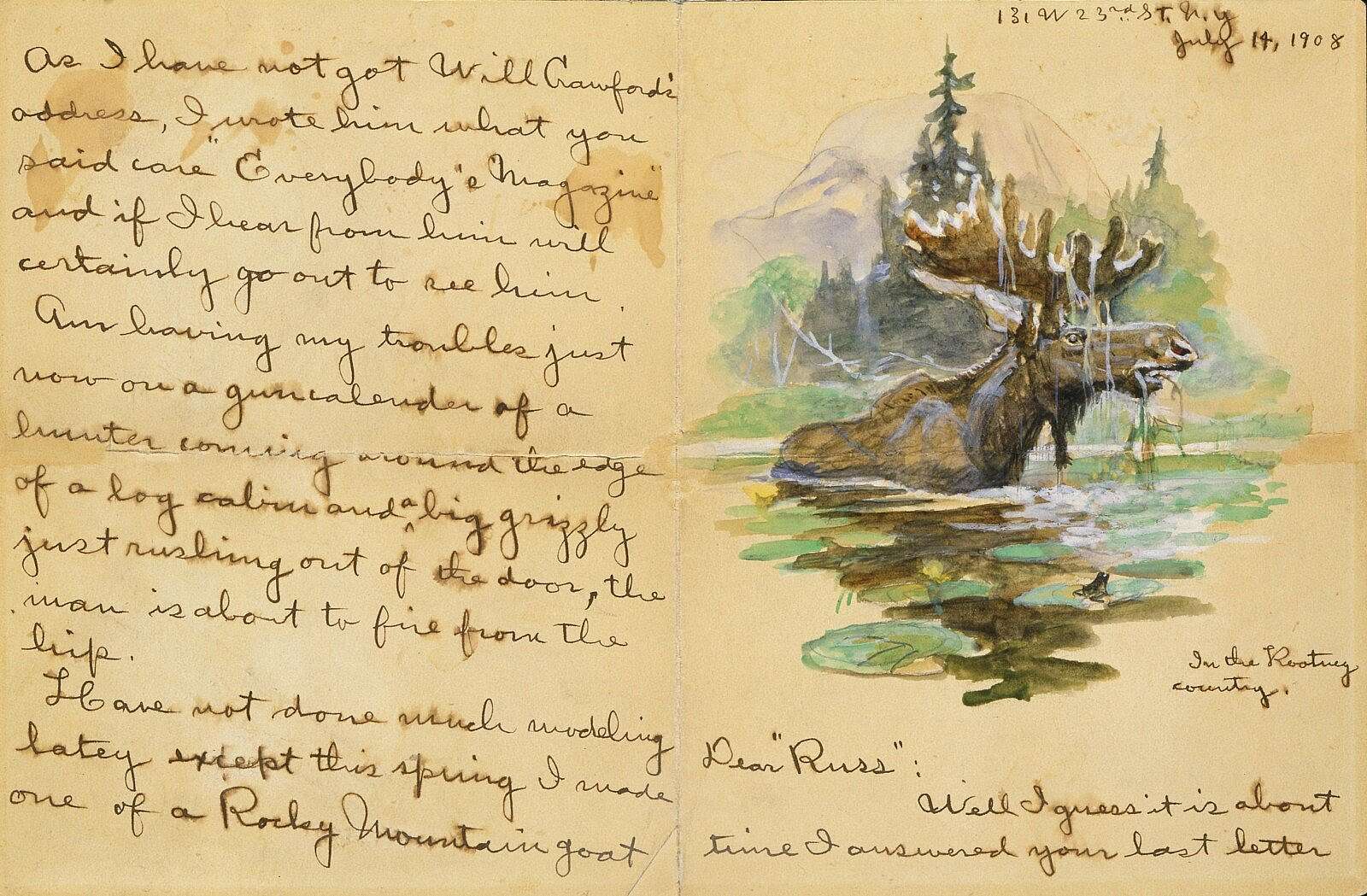

The book was renamed The Call of the Wild, and it made Jack London an international celebrity. It was Philip R. Goodwin’s big break. From this point on, Goodwin was in demand. Calendars, outdoor equipment companies, and magazine jobs all flowed; most notably, Theodore Roosevelt chose Goodwin over peers like Charles M. Russell and Carl Rungius to illustrate African Game Trails. Possessed of an intense work ethic, Goodwin worked six days a week at his studio, taking Sundays only to paddle his canoe on Long Island Sound.

Goodwin was methodical about gathering material. Starting out in Maine and New Brunswick, he gradually moved his way west, taking summertime trips where he would sketch the landscape for use in later paintings. He spent two summers, in 1907 and 1910, with Charles M. Russell at his Bull Head Lodge on Lake McDonald in Montana. They seemed to connect immediately, building model sailboats to race on the lake. Goodwin’s influence had a pronounced effect on Russell, who was self-taught. After his time with Goodwin, Russell’s colors became richer and more melodramatic.

Charlie Russell’s letters to Goodwin reveal a puzzlement about why he didn’t want to come out again. In reality, Goodwin felt he had to go to Alberta instead to gather more landscape. But there was more to it than that. While Russell called himself an illustrator, he was actually catapulted into the ranks of the rich and famous, largely due to the machinations of his wife, Nancy, who served as his agent. And while the Russells ended up spending time in Europe and winters in California, Goodwin remained an illustrator, bound to New York and the publishing houses there, and therein lies the rub.

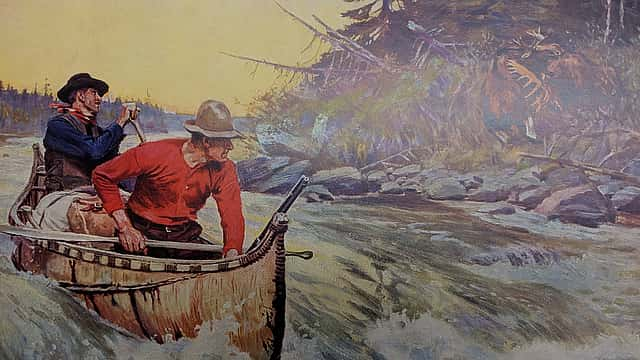

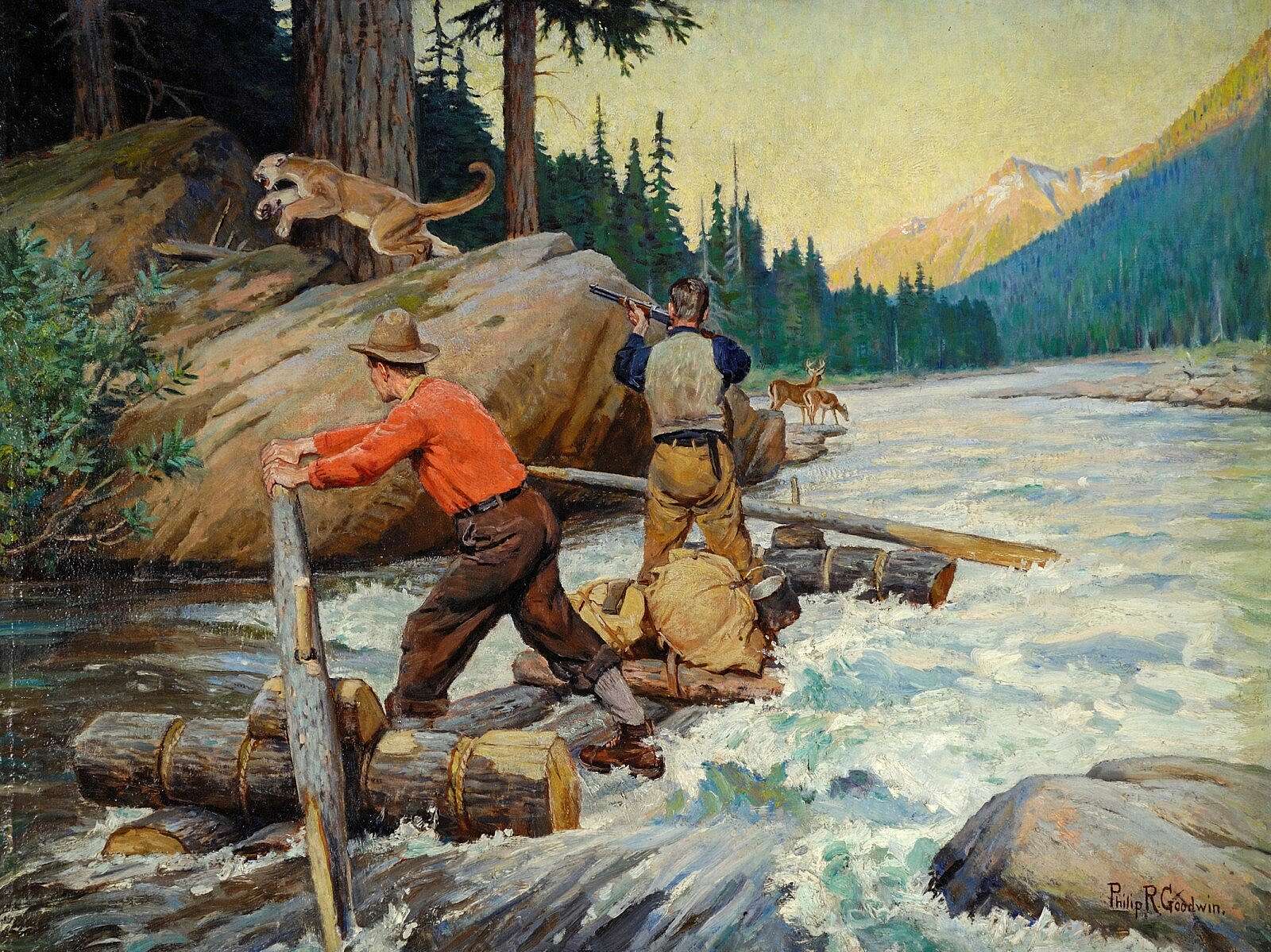

When I gave an early version of this talk at a gathering of Wyoming game wardens, I showed them a Goodwin painting featuring two canoeists being confronted by a mountain lion. I asked them if they or any of their friends had ever seen a mountain lion perched on a log over a stream as they paddled by (the answer was no.) As his career went on, Goodwin’s work became increasingly focused on predicament scenes which are somewhat unrealistic.

Over the course of Goodwin’s career, where he had started out painting from the point of view of an animal, his work became more focused on people. At a certain point a preponderance of men in red shirts start appearing in his work. This is because the rifle and sporting goods companies that commissioned his work told him to do so. Then women start appearing. Companies decided they wanted to expand their market to include women, and he was told to stick them in his work.

But it’s worse than that. The letters that survive reveal a pickiness that would drive anyone crazy. The Philip R. Goodwin Collection in the McCracken Research Library, gift of Goodwin’s sister-in-law Neva, reveals the story.

Brown and Bigelow, a Minnesota-based calendar company, wrote:

We wish you would make a couple sketches of the following – show the same two trappers that we have had in the past, with the red and blue shirts, then have a young boy with the same type of an outfit, probably brown shirt, who has just been taken along on his first trip into the woods.

Show these trappers with the boy assisting in building a log cabin on some spot overlooking a lake. Then introduce a bit of animal life and action, possibly a bear and its cubs, rounding a corner somewhere, or in some playful action, at least adding some human interest to the picture itself…. Then if you have any other ideas you want to send along, do so.

What would this be like, as an accomplished artist, to have to cater to such programmatic demands?

And later on, the same company found that their own suggestions weren’t very good:

We find men are hollering for the old time Goodwin subjects, the kind of subjects that had a big thrill in them. They seem to recall the one of the two men on a raft with a bear trying to upset them…. In other words, it seems like the men are after one real thrill in their pictures, and it seems like Mr. Goodwin can give it to them…. Perhaps we have gotten ourselves into a rut, and we are appealing to you to try to pull us out with a bang up subject.

People are always talking about “selling out,” in terms of art. But what if selling out is the only thing between you and the street? If you were in Goodwin’s position, what would you do?

I think the individuals in Goodwin’s painting that he identified with were not the manly men he pictured fishing and hunting, but the wildlife. As a prodigy who became trapped in his own formula, Goodwin ultimately became not the men in his paintings, but their quarry. Mr. Goodwin, the child prodigy who identified so intensely with wildlife, finds himself squarely in the crosshairs of the consumer age.

Goodwin never married. After his father’s death in 1903 he assumed care of his mother, and they lived together for the rest of her life. Carl Rungius, the noted wildlife artist, said “Goodwin was a fine painter and would have gone forward fast had he not had an ailing mother that kept him tied close to his studio.” A quiet man, Goodwin didn’t have the aggressiveness or marketing savvy to catapult himself to the next level beyond commission work for calendars, books, and magazines.

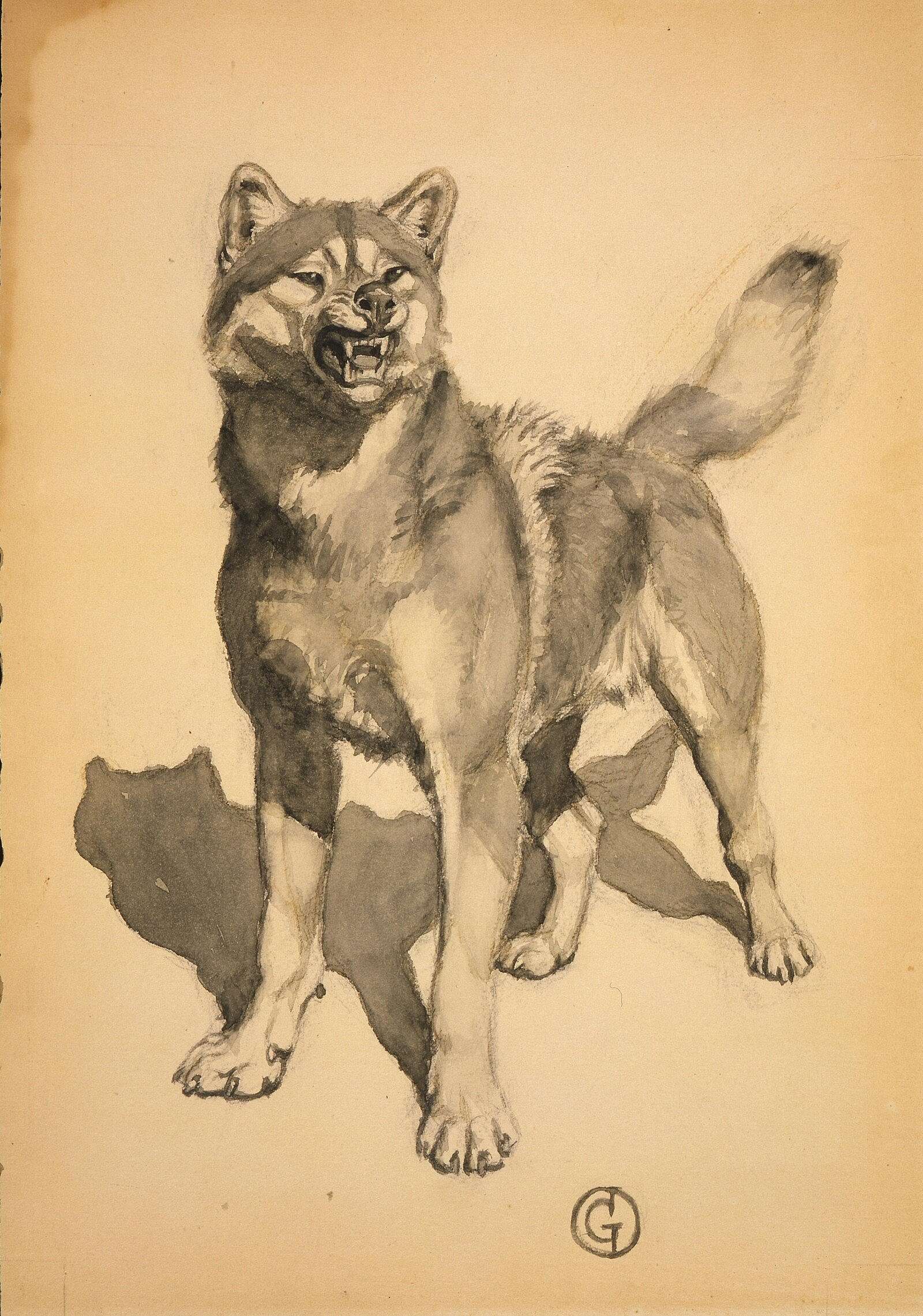

Painting is a solitary occupation, and after his mother’s death he was left alone. The art market dried up with the 1929 stock market crash, and the failure of the Mamaroneck Bank in his hometown left Goodwin financially ruined. He rented out their house out and moved into his artist’s studio out back with his dog. It’s unclear whether he had the money for heat or not, but he came down with pneumonia. The cook employed by Philip’s tenants found him lying on the floor unconscious, his dog sitting loyally over him. He died on December 13th, 1935. He was 54 years old.

Dying in obscurity happens to plenty of artists. Few attended Philip Goodwin’s funeral, and his passing was little noted in the press. What happens less often is that at a certain point his work began a revival. In his case that revival began in about 1973. Around this time his name started appearing in books and articles about Western and wildlife artists. His prices began to creep up. Last year, a Goodwin brought $786,500 at auction. Philip Goodwin may have died alone with his dog sitting over him, but today he’s a hot commodity.

In 1990 his sister-in-law Neva Goodwin donated some of Goodwin’s correspondence and artwork, along with a first edition copy of The Call of the Wild, to the Buffalo Bill Center. It is difficult to know what the young Philip Goodwin would have thought had he known that this book is one of the McCracken Library’s treasured items, much less how he would succeed, struggle, and ultimately, years after his passing, prevail.

Kim has since gone on to become a successful artist. Her work was featured in Cody’s Rendezvous Royale Downtown Annual Art Walk last fall. I didn’t realize the prices her work was pulling. You can read more about Kim and her work here.

Written By

Eric Rossborough

Eric has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the McCracken Research Library. Eric comes here from Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.