Pulp Fiction

When Bill Hayes was thirteen years old, he spent several days at a mine in the Bighorn Mountains. Some cousins had invited Bill, his Dad, and his brother up. They were hoping to strike it rich with uranium. The road was barely passable. They got up there to find a cabin with a man living in it. He lived on fried bologna and rabbit. Lean and fit, he spent his days hacking out ore and loading it into burlap bags. The cabin was filled with magazines with garish covers: Westerns, detective stories, and the like. Bill and his brother had never seen anything like them.

Cheap Thrills

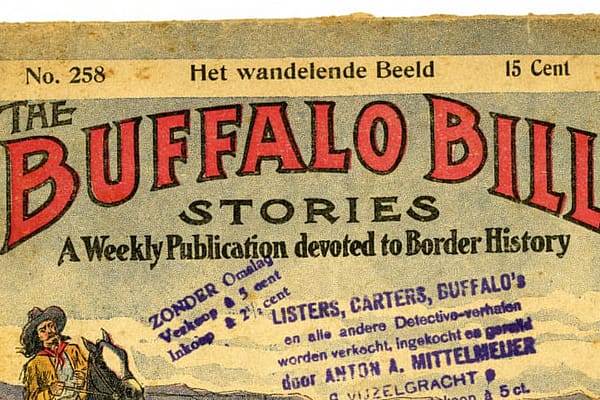

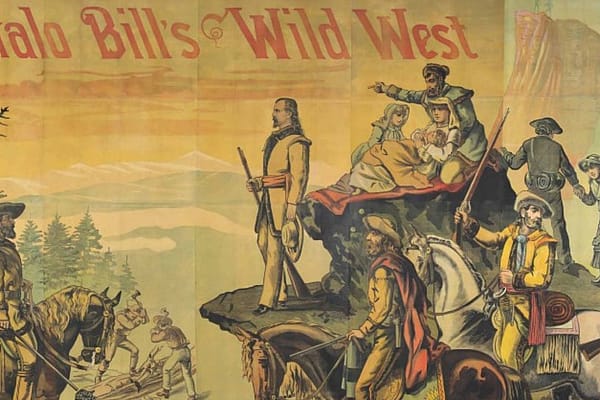

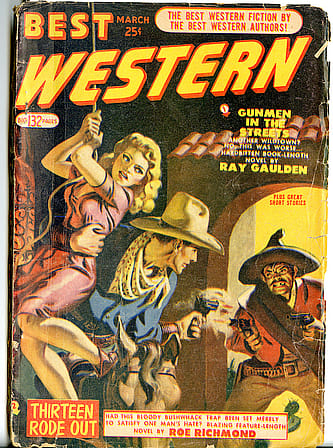

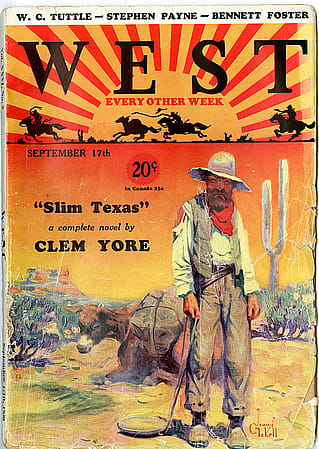

Before television, before video games, there were the pulps. Cheaply printed and mass produced, “pulps” referred to the low quality of paper used for these magazines of fast-moving short stories. The popular genres of the time were all represented: Westerns, science fiction, detective stories, and racy romances, among others. City newsstands in the 1920s and ‘30s were jammed with pulp fiction magazines for sale, and workers and executives read them on the subway and in their homes or rooming houses.

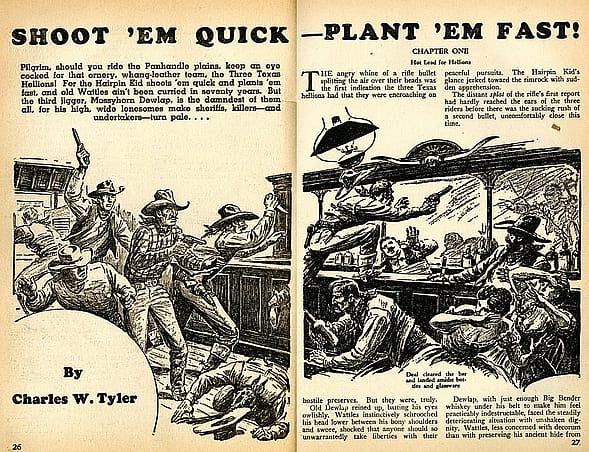

Many celebrated writers, among them Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and Tennessee Williams, all started out in the pulps. It was every pulp writer’s goal to graduate to mainstream magazines, or “slicks,” which paid better. “Slicks” referred to the glossy paper these magazines were printed on.

Hudson River Cowboys

While Western novelists such as Zane Grey and Owen Wister based their works on actual trips to the West, that was not a luxury afforded to many freelance writers, who frequently scraped to get by. Many writers of Western pulp fiction were Easterners who had never been west of the Hudson River. They got their information from libraries. These were called “Hudson River Cowboys.” When the artist Nick Eggenhofer published his first cover illustration for Western Story, he studied the cowboys on movie sets in Fort Lee, New Jersey.

The Short-cut Method

The emphasis was on speed: speed of production, speed of reading, and speed of disintegration. The artists stuck to primary colors: red, yellow, and blue. Artists with several deadlines each week used the “short cut” method: they read a portion of the contents and illustrated the story based on what they had read. The covers frequently had nothing to do with the stories within. No one cared.

The artwork was photographed and shrunk down to fit the cover. The originals were then tossed. This wasn’t anyone’s idea of high art. Today the cheap pages of pulp magazines, where they exist, are browning and disintegrating as we speak. They were not built to last, but to provide people with escapist entertainment. The pulps had a wide audience. Pulp publisher Henry Steeger claimed that President Harry Truman and gangster Al Capone were among his subscribers – at the same time.

Entertainment in an Isolated Cabin

Pulp fiction was a product of the industrial age, but paradoxically these magazines represented a look toward the past. Today Bill Hayes is a McCracken Library Board Member. He visited that mine camp in 1961. The age of the pulp magazine was already over. In that isolated cabin, a hard rock miner and sheepherder passed his free time reading exaggerated and romanticized versions of his own life. Westerners have always loved their own myth.

The pulps took a hit with the paper shortages in World War II, but their ultimate demise came with the advent of television. By the 1950s they had disappeared entirely. “I wrote pulps for several years and at the end of the time was making a very good living at it,” Louis L’Amour said. “Then overnight they were gone like snow in the desert.”

Written By

Eric Rossborough

Eric has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the McCracken Research Library. Eric comes here from Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.