The Twilight Life of Charles King

Popular nineteenth century writers like James Fenimore Cooper and Mark Twain were so popular they got their own library call number. This is something twentieth century writers, even really popular ones, cannot boast. Mark Twain’s autobiography was a best-seller when it was released in 2010. Supposedly he didn’t want his ruminations on himself coming out until 100 years after his death. Nonetheless, the success of The Autobiography of Mark Twain took the publishing industry by surprise.

Not all authors, even popular ones who get their own call number, stand the test of time so well. The McCracken Library boasts a complete (or near complete) selection of works by General Charles King. We also have his archive. In my tenure here no one has come to look at King’s archive, and people, Western historians and military historians alike, often don’t even know who he is.

A Seventh Generation Soldier

You could make a good living as a writer in the early 1900s: King must have done pretty well. He wrote over sixty books. Cadet Days: a story of West Point; An Army Wife; Trumpeter Fred; A War-time Wooing: romanticized versions of army life that may have actually made young boys of the era take up “The business of arms.” It’s hard to know now.

Charles King had roots. A seventh-generation soldier, he was the son of Civil War general Rufus King, and the great-grandson of another Rufus King, who was one of the signers of the United States Constitution. Charles served under his Dad during the Civil War as part of the Wisconsin Iron Brigade. What actually was he going to do, other than become a soldier? Charles King received his appointment to West Point from Abraham Lincoln himself. He graduated from West Point in 1866 and served in the Fifth Cavalry under General George Crook in the Indian Wars.

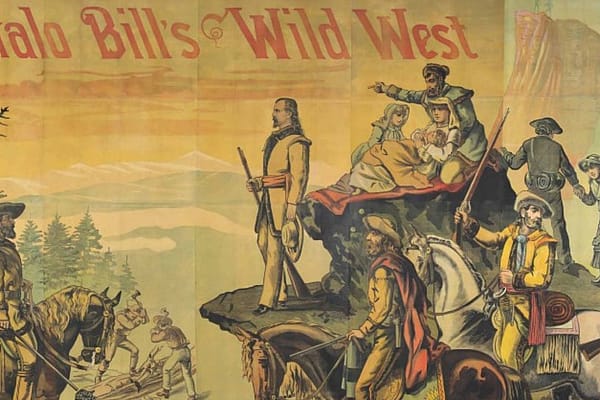

Buffalo Bill’s Buddy

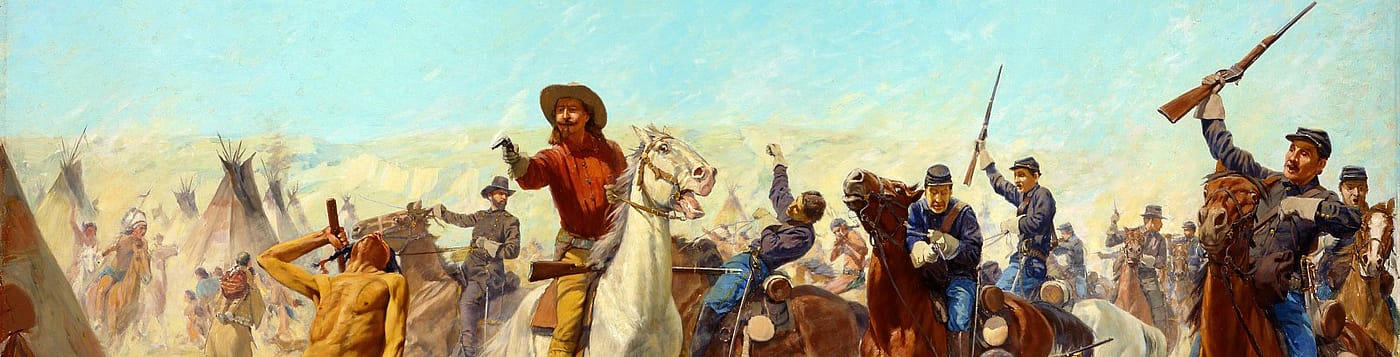

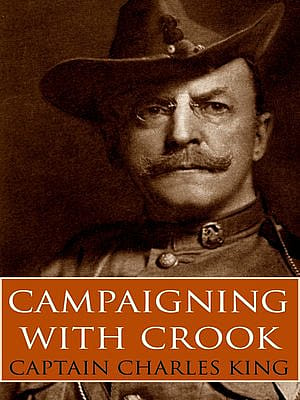

It was during this period that King became friends with Buffalo Bill Cody, the unit’s scout. King was shot in the arm during a battle with the Apache in 1874; the shattered bone never healed properly. Forced out of active cavalry service by this injury in 1879, this also resulted in his first book, Campaigning with Crook, which has been reprinted many times. Campaigning with Crook is still considered a vivid and accurate depiction of U.S. Cavalry life in the American West, and remains King’s most popular work.

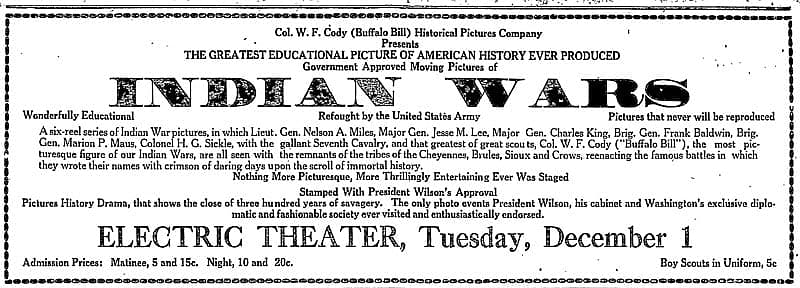

But he went on. The romanticized novels King put out were published in over 400 different editions. Charles King remained friends with Buffalo Bill, and wrote a screenplay for the silent films Cody had in mind, to be called Indian War Pictures. It’s funny to think of Charles King in connection with a movie.

Boundless Energy and Relentless Drive

A man of boundless energy and relentless drive, King, historian Don Russell wrote, “Was the only soldier in American history to wear campaign medals from five wars – the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, Philippine Insurrection, and World War I – in addition to a Silver Star awarded after an Apache fight in 1874. King was credited with seventy active years of military service.” He served in the Wisconsin National Guard as a drill instructor into his eighties. This was not an allowance made for an old man who retained his vitality. It was ordered by the United States War Department. King’s contributions were valued.

An Accurate Depiction of Life at Frontier Army Posts

King’s novels reveal a bright man and a skilled writer. He understood dialogue and character development; his novels put you inside the nineteenth century military with its politics, character assassinations, and occasional pleasures in the form of dances and singing around the piano: the kind of amusements people took for themselves before mass media. Charles King was a gentleman soldier who lived in a world of romance and chivalry that did not persist into the twentieth century. King depicts a world that was washed away with World War I and the advent of modern warfare. He was not washed away with it. He continued to serve nearly until his 1931 death, but his works and entire personage reveal a man out of time.

What strikes me is how King was the relic of bygone era, even in his own time. I don’t know how aware he was of this. As part of the Wisconsin National Guard, he helped train troops for World War I. How could he know the advent of twentieth century warfare would blow his concepts of chivalrous nineteenth century horse-based warfare to smithereens?

Written By

Eric Rossborough

Eric has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the McCracken Research Library. Eric comes here from Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.