The Reinvention of Mickey Cochrane

At night, when he was a kid, Mike Cochrane would practice running down Mt. Prospect Street in his hometown of Bridgewater, Massachusetts. He wanted to be in the Olympics, so he took every chance to sprint that he could. Mt. Prospect Street runs right by the town cemetery. “That stretch of road at night was pitch dark and scary,” he later said. “Boy did that make me run like hell.”

Mike Cochrane had to be the best at everything. Everything he did was possessed of an insane drive. He played the saxophone, hunted and fished, and was active in community theatre. One day when a boy was skating on a nearby pond and fell in, Mike crawled out on the ice while his friends held his legs and pulled the skater to safety. He starred in football at Boston University and would have gone on to play for the NFL had it existed in anything other than a nascent form at that point.

No matter. Mike turned to baseball. He made himself a catcher, a position he wasn’t any good at, in a sport he hadn’t excelled at, spending hours and hours catching pop flies. He signed with the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League, and Connie Mack, impresario of the Philadelphia A’s, liked Cochrane enough that he bought the whole team in order to get him.

“When I first saw [him] he wasn’t much,” said Cy Perkins, who lost his catching job to Cochrane. “He made himself great through sheer hard work.” Cochrane went on to lead the A’s to World Series titles in 1929 and 1930. Mike, as he was known to his family and friends, was christened Mickey by the press corps. His teammates called him “Black Mike.” He wanted to win. Ty Cobb was finishing out his career with the A’s when Cochrane came into his hotel room after a loss and stomped his hat in an outburst of rage. Cobb, a notoriously sore loser, was impressed. “It was one of the greatest examples of what it means to be a “hard loser” that I’ve ever seen,” Cobb said.

By 1933, Connie Mack, who had lost a lot of money in the 1929 stock market crash, sold off the powerhouse team he had built to pay his expenses. Jimmie Foxx and Lefty Grove went to the Red Sox. Cochrane went to the Detroit Tigers, with the proviso that he would catch as well as manage. “I saw this was Mickey’s chance,” said Mack. “I owed him something extra for his loyalty, so I just couldn’t stand in his way when he could better himself.”

He bettered himself all right. As player-manager, Cochrane led the Tigers to a pennant in 1934 and a World Series championship in 1935. He was a master motivator, cajoling some, but he went out to the mound and punched one pitcher in the ribs when he thought he wasn’t trying hard enough. Sportswriters who had spent years observing professional athletes knew they were seeing something different. Cochrane was “Unlike any other man who ever managed…the most emotional player in baseball,” wrote Harry Salsinger.

Mickey told another, “I’ve got to win. There’s no if’s or but’s about it. They’d ride me out of Detroit on a rail if I lost.”

1935 marked the first time Detroit had won a World Series. In the depths of an economic depression, Mickey Cochrane became a national hero. People named their children after him. Oklahoma farmer Mutt Mantle decided one of his kids was going to be a baseball player before he was even born: he named him Mickey.

Detroit’s first championship came at a time when things were starting to turn around for the auto industry; this success was linked to Mickey Cochrane, who had nothing to do with the economic fortunes of Detroit and had only lived there two years. “His spirit has done much to lift Detroit out of the despondency it slipped into a few years ago,” said Malcolm Bingay, editor of The Detroit Free Press. Bingay said this not in print, but to a teeming crowd in Cochrane’s hometown of Bridgewater, Massachusetts, who had turned out to celebrate their hero.

It should have been enough, but it wasn’t. Roommate Bing Miller would wake in the morning to find Cochrane smoking and looking out the window. “Every mistake caused Cochrane a new agony, every defeat cost him a night’s sleep,” Salsinger wrote.

He didn’t seem to have the athlete’s facility to shut things off, to put defeats behind him and move forward. Not only that, now he was in charge of twenty-five guys. “When I was a player I worried only about myself. Good money and easy work,” Mickey said. “Now I have to worry about everybody. I have to see that they’re in shape and stay in shape. If one of them eats something that makes him sick, it makes me sick too.”

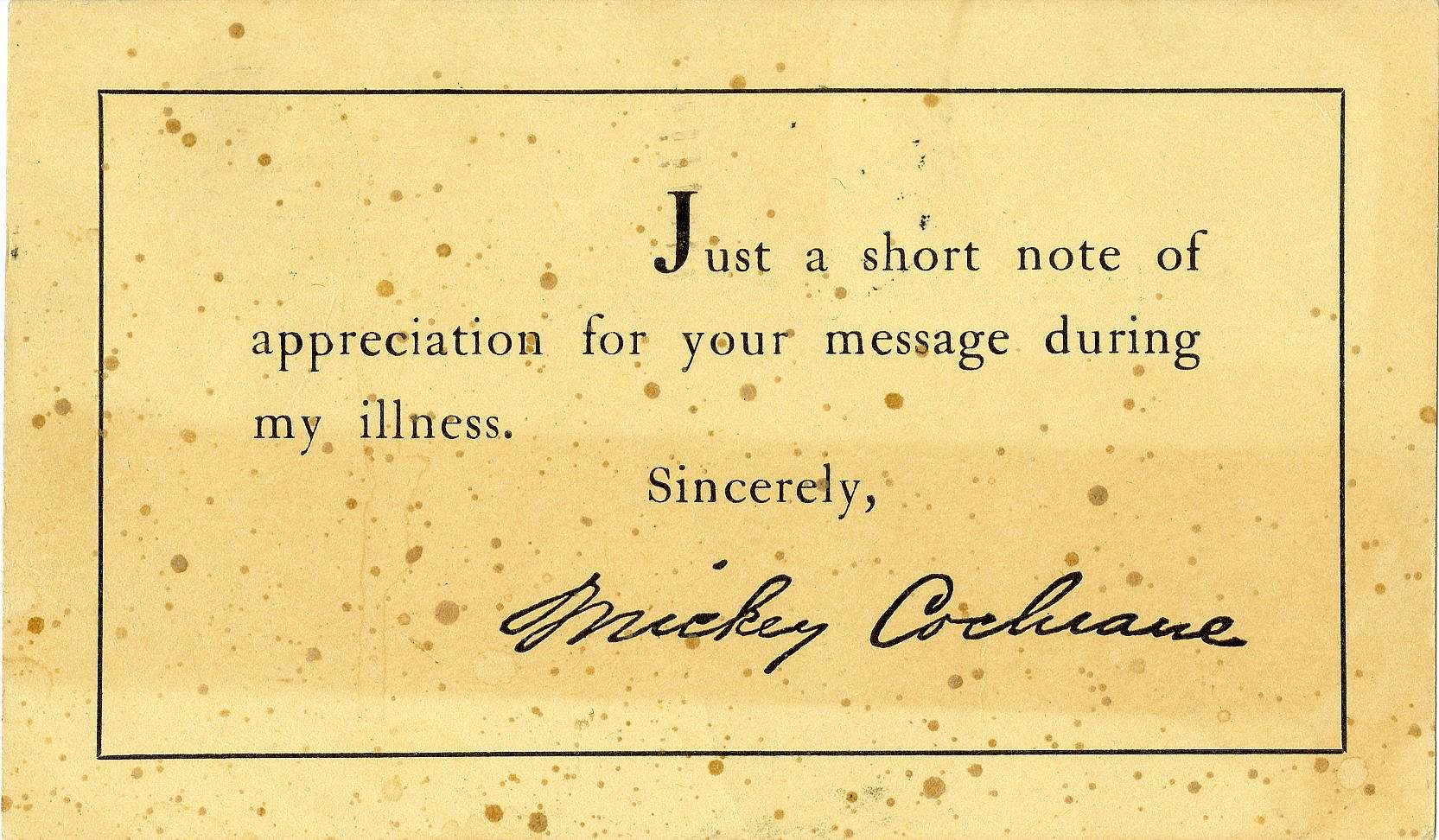

It all came to a head on June 4, 1936. The Tigers got off to a terrible start that season. Mickey had spent another sleepless night. He put himself in the lineup anyway, and in the third inning hit an inside-the-park grand slam. He went back into the dugout, put on his catcher’s gear, and collapsed.

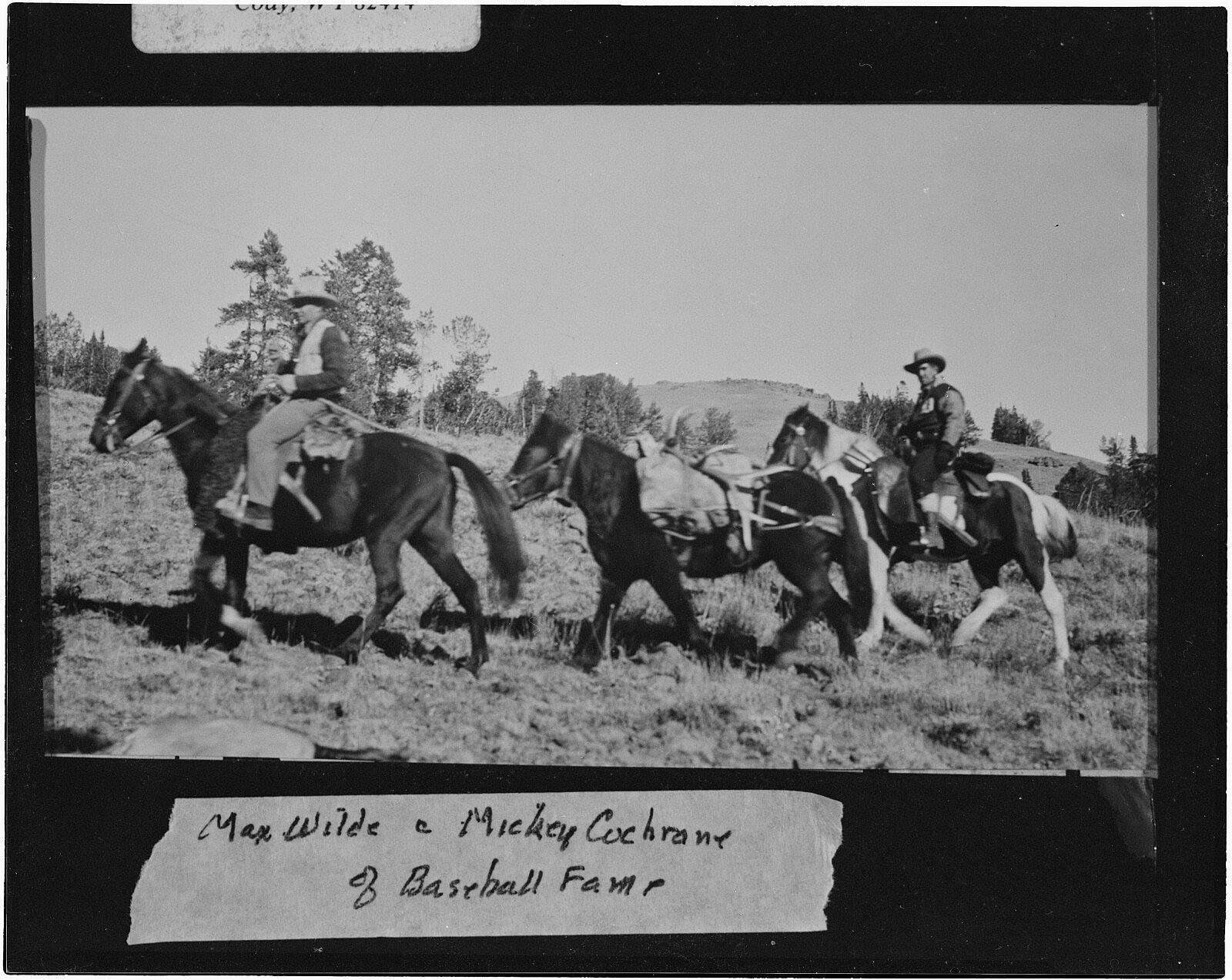

In those days tough guys did not go to psychologists. Mickey spent eleven days in the hospital, some time at his folks’ house in Bridgewater, and then he and his best friend, future four-star general Emmett “Rosie” O’Donnell, boarded a plane to Billings, Montana. And after a drive to the Irma Hotel in Cody, they met hunting guide Max Wilde.

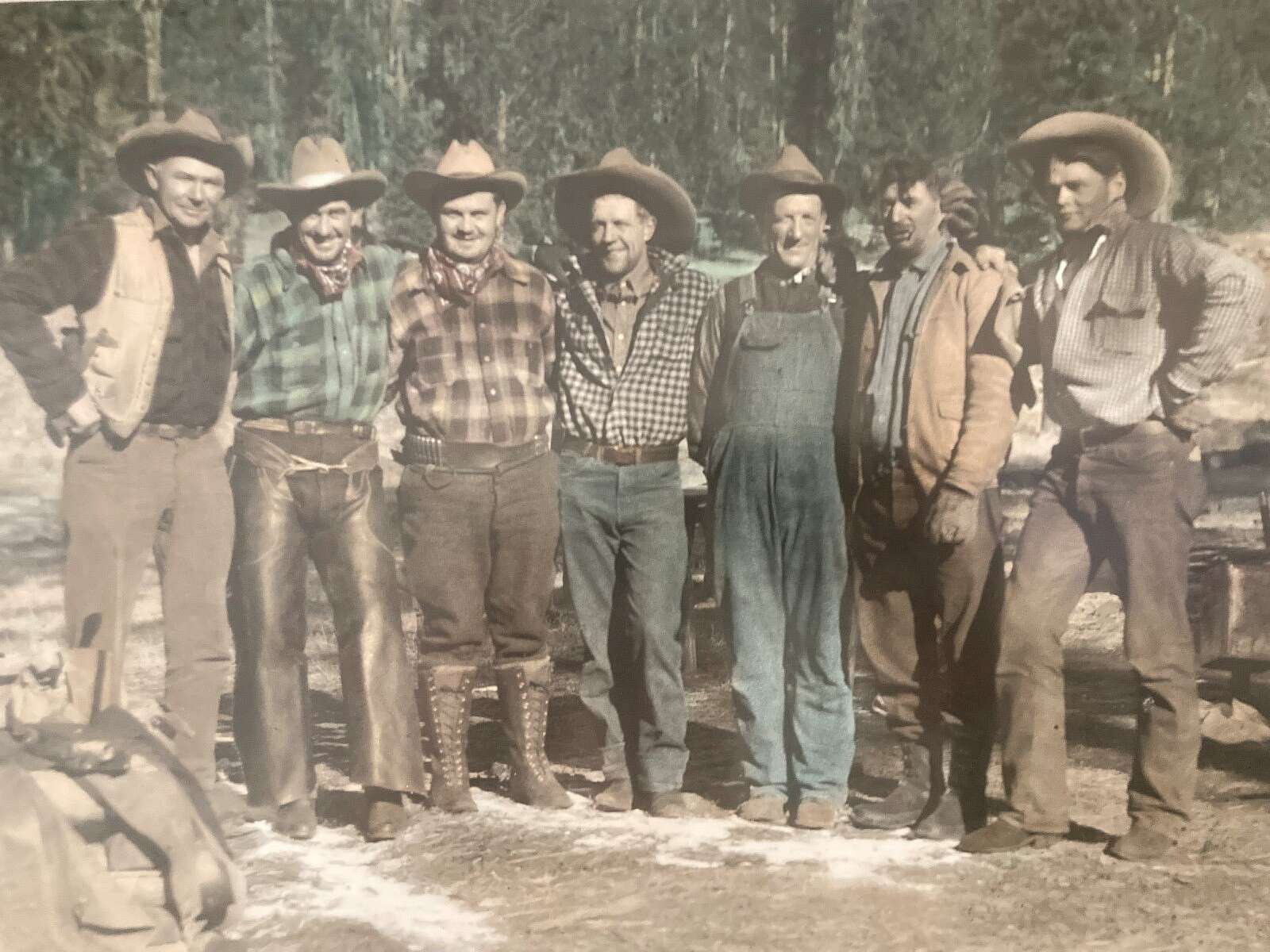

I have tried to figure out how Max Wilde got the corner on the Major League Baseball trade. Most of Max’s baseball clients consisted of people who had played for the Philadelphia A’s at some point. What we know is that Max’s “dudes” included Ty Cobb, Bing Miller, Jimmie Foxx, and Lefty Grove, among others. All of these were former teammates of Mickey’s. And they all hunted with Max Wilde. I can only figure that these guys rallied around one of their own in a time of trouble and thus, Mickey came out here. The Irma Hotel was and is the place where people heading out on guided trips into the backcountry around here go to meet their keepers. Mickey was under strict orders from his doctors not to read any baseball news.

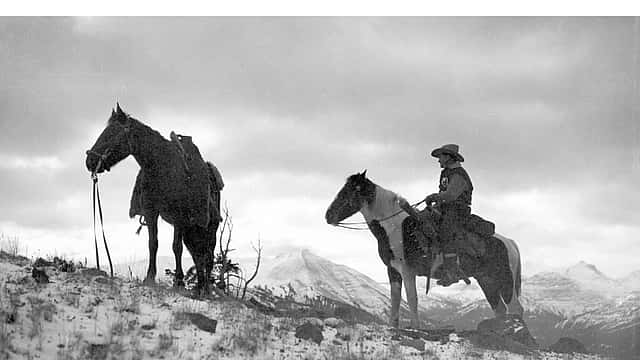

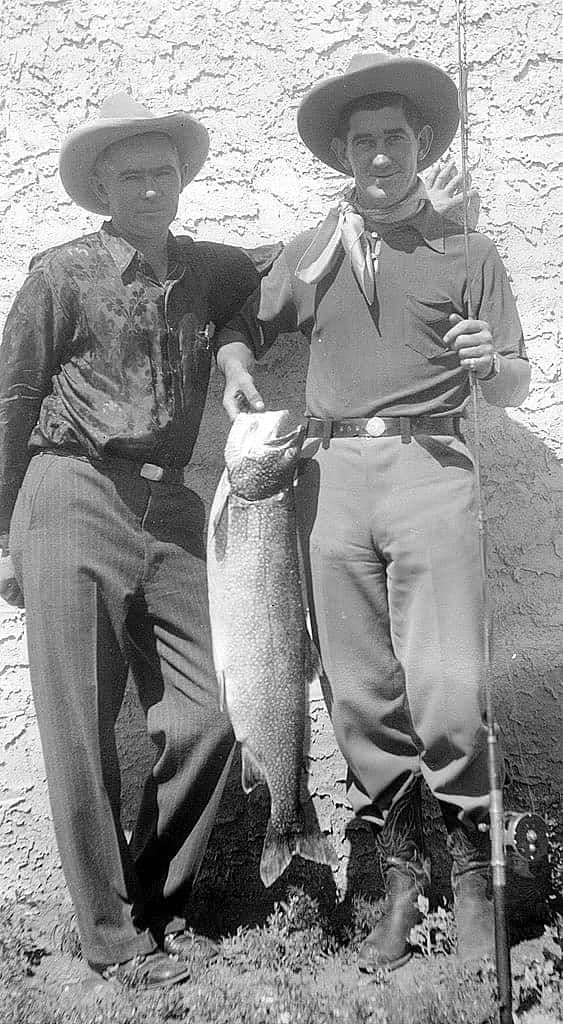

He was supposed to stay for two weeks. He ended up staying for more than a month. Max and Mike went fishing and riding. The photos of the two of them together are interesting. In all his photos Max Wilde has a serious expression on his face. He knows he’s in charge of the safety of people in the backcountry. In his photos with Cochrane, Max Wilde’s body language is positively protective. He knows someone has come to him in a time of need and Max is going to make sure that nothing bad happens on his watch.

When I first came to work at the McCracken Research Library, as a native of Massachusetts and a baseball fan, I was fascinated by the photos we hold of Mickey Cochrane. Particularly the one featuring Mickey holding a giant trout. According to my colleague Mack Frost, this was taken in front of his uncle Will Richard’s taxidermy shop, and they probably stopped by just to show it off.

I showed this photo to my volunteer, Lolly Jolley. Lolly is an astute woman and was the source of much of my information about the town of Cody when I was getting settled here.

“He’s not from around here,” she said. Lolly wouldn’t know Mickey Cochrane from a hole in the wall.

“How do you know?” I asked.

“Look at the expression on his face,” she said. “Look at the way he’s dressed. That bandanna around his neck? Come on.”

I took a lot from this. Here was a guy who had hit bottom, or at least as close to bottom as a world-famous athlete who makes the cover of Time magazine is likely to get, and he had come out here and reinvented himself. Like me, Mickey Cochrane was from Massachusetts. If he could do it, why couldn’t I?

Mickey Cochrane’s baseball career did not last all that much longer. What he did do was buy a ranch outside Billings. He and his brothers more or less relocated to the area. His brother Archie used Mike’s industry connections in Detroit to start an auto dealership, Archie Cochrane Motors.

When Cochrane was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, he didn’t show up. “It didn’t seem important to Mike,” his wife Mary said. “We were out West at the ranch at the time.”

Written By

Eric Rossborough

Eric has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the McCracken Research Library. Eric comes here from Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.