A Broadway Guy: the Second Life of Bat Masterson

When Bat Masterson and his brother Ed heard of a job building a railroad grade in the summer of 1872, they took it. They had been out on the Kansas plains, skinning buffalo. The hides were pulled off, to be turned into coats, blankets, and most importantly, belts for the factories that were growing in Eastern cities. The meat was left to rot. The air was full of flies, the stink of rotting carcasses, and the unyielding sun. The air boomed with the sound of rifles. This was the last push before the buffalo were wiped out entirely. A whole economy was built around it. In a few years the buffalo would be gone, replaced by a sea of bones which in turn were picked up and shipped east to be ground into fertilizer.

Raymond Ritter hired Bat and Ed to build the grade, which was to run from Fort Dodge to Buffalo City. Ritter set the boys to work and left to get the money. He would be back, he said.

He wouldn’t. Empty handed, Bat and Ed, joined by their brother Jim, took another job with a buffalo hunting crew and headed back out onto the plains, this time in winter, to a world of howling blizzards and bitter cold. In January of 1873, Jim and Ed went back to their folks’ farm in Sedgewick, but Bat hung out. Buffalo City, recently rechristened Dodge City, was a cluster of tents, but he was attracted by the gambling and the nightlife.

It was at this point that Bat heard from a friend that Raymond Ritter would be coming back through town, eastbound, over the new railroad tracks. When the train showed up, Bat got on board and walked slowly through each car. Raymond Ritter was shocked to see Bat Masterson, and more shocked still to see the barrel of a revolver pointed at his face. Ritter howled that he was being robbed as Bat hauled him out on the platform, but that didn’t help him any. None of the gathering crowd interfered.

“I’m only collecting what you owe me, and everybody here knows that. You ran out on me and Ed, but now you’re going to pay up.”

He got his money. In true Western fashion, Bat Masterson led everybody to a saloon on Front Street and put up for drinks. He was nineteen years old.

The buffalo gone, the economic focus of the newly named Dodge City would change, in the in the fast-changing resource exploitation economy of the frontier, to cattle. In 1877, Bat was elected Sheriff. He and his buddy Wyatt Earp practiced a novel form of 19th century policing: buffaloing. Instead of shooting the drunken cowboys who flooded the town in summer, they would knock them in the head with their revolvers and throw them in the clink to dry out. In the context of the time this represented enlightened, community-based policing.

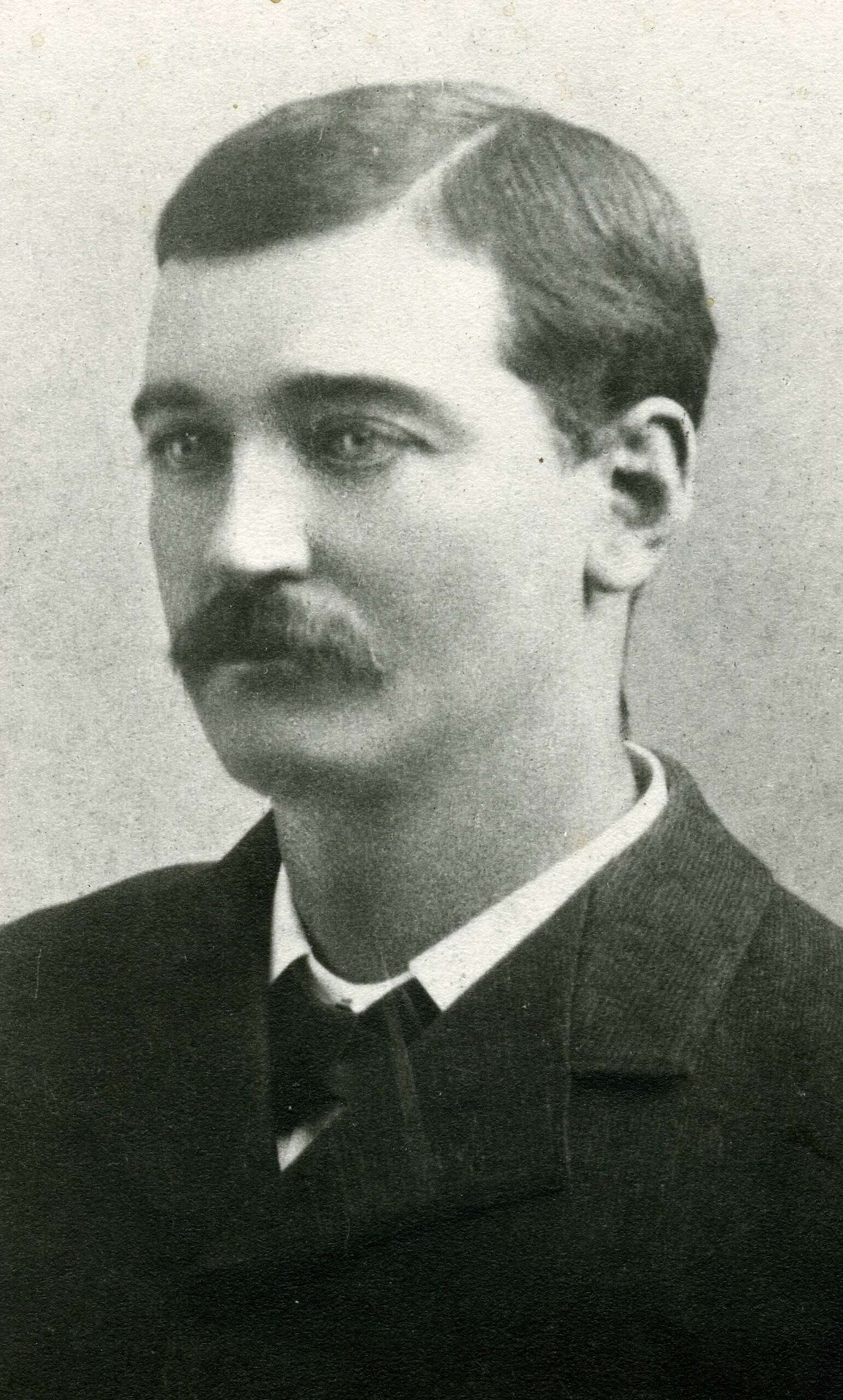

“Bat always had an air about him, a blend of cockiness and charisma that seemed to charm just about everyone he met, and a style that seemed to invite good times,” wrote a historian. He repeatedly demonstrated utter fearlessness. He had no problem facing down entire mobs by himself. There are numerous accounts of him traveling hundreds of miles to help friends in trouble. But being a sheriff was a form of supplemental income for him. What he really liked was gambling.

Working on the side as security and as a dealer at various saloons and gambling joints, this got him on the wrong side of some community boosters, who considered Bat and his friends an element that had to be eliminated in the name of progress. He lost the next election by a few votes. Bat took the side of the gambling contingent with glee. This led to Bat’s first foray into journalism, his own self-created newspaper, The Vox Populi.

Written solely to influence the outcome of the 1884 elections in Dodge City, The Vox Populi is an entertaining screed of Latinate words and personal insults. “Ford County does not want the scum and filth of other communities for county attorney, such is Burns the Republican candidate.” And, “E. D. Swan would be a nice man to have charge of the poor widows and orphans of Ford County, after turning his aged and decrepit father out on to the streets to die of starvation.”

Bat’s slate of endorsed candidates won, and he folded The Vox Populi after one issue. The Dodge City Globe noted that while “The news and statements it contains seem to be of a somewhat personal nature…. The editor is very promising; if he survives the first week of his literary venture there is no telling what he may accomplish in the journalistic field.” Bat Masterson would not return to journalism for another twenty years, but the seed had been planted.

By 1884, Bat had assumed an itinerant life, working a gambling circuit that included, in part: Dodge; Las Vegas, New Mexico; Denver; and Kansas City. He dressed nice. “W. B. Masterson is well-known in this city. He is a handsome man, and one who pleases the ladies,” wrote one newspaper. Affable and good-humored, in 1885 Bat was voted most popular man in Dodge over the 4th of July and given a gold-headed cane and a watch.

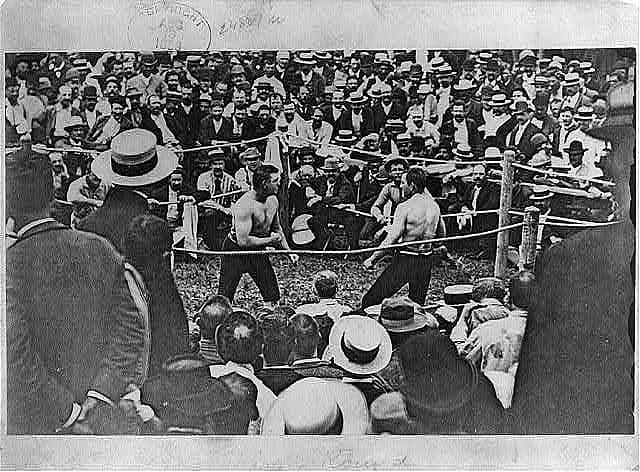

Meanwhile, he dove headfirst into what would be the consuming passion of the rest of his life: boxing. Bat did not like other sports. Baseball, he wrote, was “almost as weird as football.” He didn’t even seem to have much interest in that most preponderant Western sport, horse racing. He worked as a referee, promoter, and manager, notably wading into the ring in 1893 in Denver and punching the opposing boxer in the face when a melee broke out.

At this time boxing was a barely legal endeavor. Boxers fought dozens of rounds bare-knuckled. Gore was common. Bat, predictably, was in the middle of “The Great Fistic Carnival” of 1896; he was hired by the Pinkertons to provide security.

Scheduled for El Paso, pressure from religious leaders who wanted to ban boxing forced the match out of Texas and across the river into Mexico. No dice. Mexican Rurales lined the south shore of the Rio Grande to make sure this did not happen. New Mexico was out, too; Congress rushed through a measure prohibiting boxing in any U.S. territory.

Bat always seemed to find himself fighting a rearguard action against people who wanted to purify the world. The match ended up being held on an island in the middle of the Rio Grande River, while Texas Rangers and Mexican troops lined the respective shores in order to watch.

When Bat fell out with another boxing promoter over a business deal and Bat resolved the issue by beating the guy with a cane in the middle of a Denver street, it was kind of time to leave. It was at this point he was contacted by the Lewis brothers.

A loyal friend and voluminous correspondent, two of the people Bat had stayed in touch with were journalists Alfred Henry Lewis and his brother William. They were impressed by Bat’s stories and fearlessness, and when they worked their way up the newspaper ladder from dusty Western towns to New York City, they dropped their friend a line. Why didn’t he just move to New York? They could hook him up with a job.

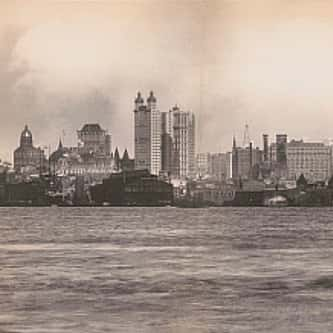

The man who had lived fifty years of rootless existence was about to find a home. How often does this happen? Are people frequently born into a situation when they would be better off in another? Bat and his wife Emma headed east. Sure, the first day in town he was arrested for carrying a revolver, but that only added to the patina surrounding a genuine denizen of the Wild West.

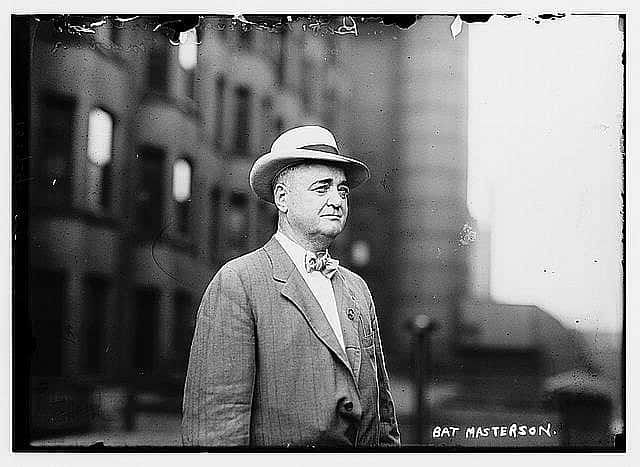

The Lewis brothers started Bat out on boxing, but they eventually let him write whatever he wanted. The New York Morning Telegraph focused on sports, scandals, and pictures of pretty girls. They had no political position other than they were against reformers. For Bat Masterson, it was a perfect fit. Bat’s three times a week column was eventually titled, “Masterson’s Views on Timely Topics,” and included commentary on boxing and anything else Bat Masterson wanted to pontificate on.

Bat Masterson showed an uncanny ability to adapt. He went from frontiersmen to product and producer of the media age almost seamlessly. A reporter asked Bat if he missed the excitement of the Wild West. Bat said, “I am a Broadway guy now.” He went from being a rootless Westerner who had no fixed address other than hotels for years to being a provincial New Yorker who didn’t even leave his own neighborhood. He wrote, “Over on the West Side somewhere there is a place called Greenwich Village. I can’t tell where or how it got the name, but it’s there nevertheless.”

“Bat had no literary style but he had plenty of moxie,” said Damon Runyon. He proved a generous mentor to an upcoming generation of prominent journalists, including Runyon, Louella Parsons, Heywood Broun, and Stuart Lake. Inspired by Bat’s stories, Lake went on to write a signal biography of Wyatt Earp. Runyon went on to greater literary fame when his short story, “The Idyll of Miss Sarah Brown,” was turned into the play Guys and Dolls, which featured a man based on Bat as the main character.

It must have been startling to go from the guerilla warfare, hard labor, heat, and dust of the Kansas plains to eating in fancy restaurants every night. Bat moved to Times Square during a period of change. Theatres were being built in the neighborhood. Colorful characters and famous people abounded. Bat counted as his companions not just journalists and boxers but celebrities such as songwriter George M. Cohan and John McGraw, manager of the New York baseball Giants.

Actually maybe it wasn’t all that different of a life. Bat had always been surrounded by colorful characters. But now he was doing it in a nicer setting. And the stage from which he held forth was Shanley’s. The restaurant extended along Broadway from Forty-third to Forty-fourth, right off Times Square. One historian noted that Shanley’s greatest attraction was not its food, but the fact that it was “The favorite loafing place of the celebrated Bat Masterson. Every night the old-time gun fighter, resembling nothing so much as a huge spider, presided over a big steak in a corner of Shanley’s grill, holding a crowd spellbound with tales which were about as wild and wooly as the West he was describing.”

Scrupulously honest, gamblers considered him “square.” In his later life he spent a lot of time, effort, and ink trying to keep boxing honest. When Bat heard a fix was on in one fight, he cornered the boxer in a hotel lobby. How much was he taking to lay down?

“$7,500,” the flustered fighter responded.

That blew that fix. Bat Masterson had a way of making people back down. People frequently commented on his eyes. Wyatt Earp wrote that Bat’s “wide, round eyes expressed the alert pugnaciousness of a blooded bull-terrier…. They were well-nigh unendurable in conflict.” When Alfred Henry Lewis was doing research on the New York underworld, he got Bat to accompany him into Hell’s Kitchen. Nothing happened. The West Side toughs knew all about Bat Masterson, apparently. They wanted no part of him, even if he looked at that point like a balding, overweight, middle-aged man.

He went out West once again, to a boxing match, and on the way east the train stopped in Dodge. Bat and his friends got out on the platform for a few minutes and ate in a Harvey restaurant, but that was it. Unlike friends of his such as Earp, who spent the summers in the California desert at a mining claim, Bat was content to eat in restaurants every night. He wrote a series of profiles of Western gunfighters he had known, at William Lewis’ behest, but he would never write about himself.

On a trip to Hot Springs, Arkansas, itself a gambling center, Bat declined the offer of a horseback ride. The man who had once ridden a horse to death in pursuit of outlaws had had quite enough of that. He showed no interest in the sort of outdoor activities that might appeal to someone who had grown up on the frontier. Bat Masterson had become a man of creature comforts. Bat’s adaptability allowed he and Emma to live comfortably in a five-room apartment.

This was notable. Many of his frontier contemporaries had trouble adapting once their bodies wore out. Wyatt Earp ended his life in near-penury and left his wife with nothing. Buffalo Bill Cody called his Nebraska ranch “Scout’s Rest.” The idea was that the broken-down Westerners who Cody had spent his youth around would have someplace to go, and not a few of them took him up on his offers of help. Buffalo Bill provided jobs and money for his contemporaries, but Bat Masterson needed no help.

Bat Masterson died at his desk on October 25, 1921. He was 67 years old. He had just completed what would be his last column. A couple weeks before his passing he had been visited by William S. Hart, the great Western movie star of the era. “I play the hero that Bat Masterson inspired,” Hart said. “More than any other man I have ever met I admire and respect him.”

Written By

Eric Rossborough

Eric has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the McCracken Research Library. Eric comes here from Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.