The Man Who Wasn’t Jim Bridger

A Well-watered Area

Jim Bridger had seen the handwriting on the wall. Between the early 1820s and late 1830s, fur brigades had moved from watershed to watershed, stripping creeks of any available fur, and now there was little to trap. Compounding the problem was the fact that the beaver market was driven by European high fashion, and beaver hats had given way to silk hats. While a lot of the surviving “mountaineers,” as they were called then, moved back home and took up farms, or moved in with Indian tribes, Bridger saw different opportunities.

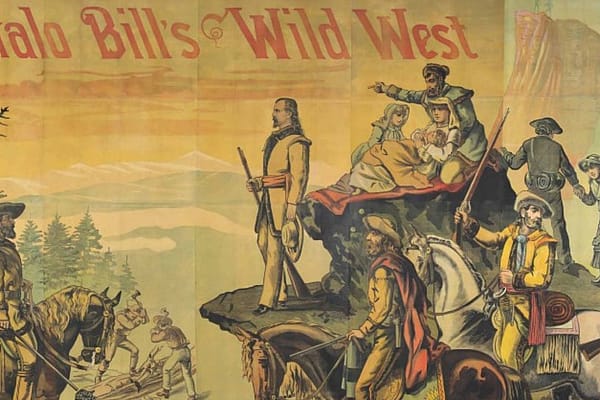

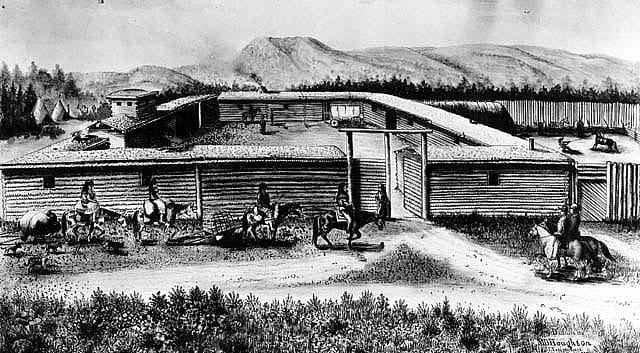

The first large groups of pioneers were passing in 1843. It is not certain whether Bridger realized that this trickle would soon turn into a flood, but he knew where to pick a fort site. Not only was the Black’s Fork of the Green River well-watered, it was a natural funnel area for people heading to the West Coast. Fort Bridger did a tidy business trading with local tribes, and supplying emigrants bound for California.

“He usually wasn’t there”

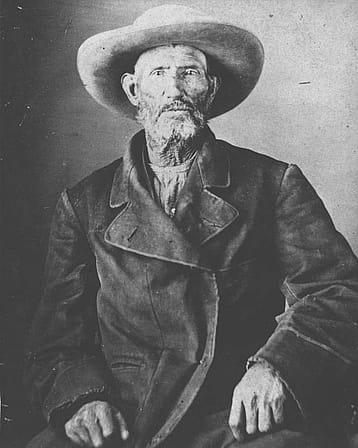

Accounts consistently refer to Bridger as “old,” and “grizzled.” Photographs show a sun-battered man, who looks like he hasn’t seen the inside of a house since, well, 1822. In 1843, however, he was a mere thirty-nine years old. Bridger’s knowledge of the terrain and landmarks of the West was encyclopedic, and he was much in demand as a guide. As a result, people passing by the fort seldom spotted the great man, because he usually wasn’t there.

William A. Carter was born in Virginia, and all his life he retained the demeanor of a southern gentleman. He served in the Seminole war, and it was in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, that he attained the position of sutler (someone who sells provisions to the army), an occupation he was to follow the rest of his life. When he came to Fort Bridger in 1857, after the U.S. Army took it over, he found a situation both big enough and small enough that he could create his own empire, and for the rest of his life Fort Bridger functioned under William Carter’s imprint, to the extent that many, during his thirty year reign, referred to it as “Carter’s Fort.”

An Estimable Wife and a Fine Piano

One observer wrote: “Mr. Carter’s general appearance denoted the scholar and the thinker, a rare specimen seen of his kind on the frontier.” While functioning in the West as, among other things, a rancher, Justice of the Peace, and Postmaster, he brought an Eastern gentility and refinement that stood out to travelers who visited the isolated outpost. All and sundry passers-by to the fort were welcome at Carter’s table, and visitors commented on the size of his library and “estimable wife,” and “fine piano.”

William A. Carter didn’t like Jim Bridger. According to Carter’s son Edward, Carter thought Bridger had lived with the Indians so long he had absorbed “all their cunning and duplicity.” Carter didn’t think Bridger’s tales of his adventures were believable, and of course he couldn’t read or write either. Carter focused on playing the role of splendid host, while Bridger was never there. While the fort retained the name of the legendary frontiersman, Fort Bridger, everyone agreed, really belonged to William Carter.

A One-of-a-kind Document

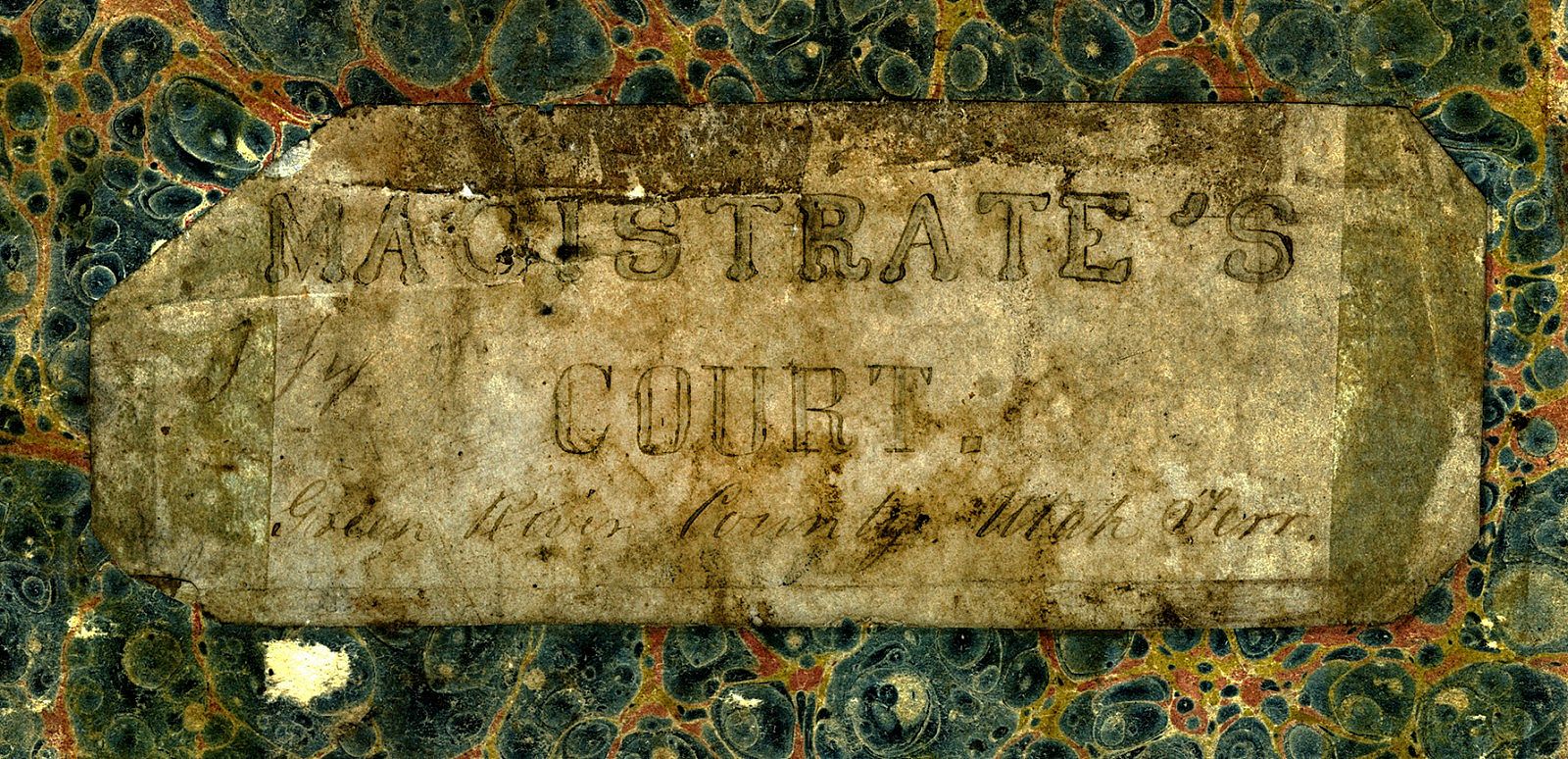

Last summer, an amazing document arrived here in the McCracken Research Library. From the outside it doesn’t look like much; an ancient ledger book with the words “Magistrate’s Court” handwritten on the cover. This came from the collection of Willis McDonald. Willis, an avid bookman and donor to our institution, was passionate about Wyoming history. He went out of his way to create a collection of early Wyoming documents, including such titles as Letter on native soda deposits near Laramie City, and Trial of Peter P. Wintermute, for the murder of Gen. Edwin S. McCook. These are items of which there are only a few in existence. The ledger book, I realized, as I opened it up, was clearly one of a kind.

The pages of the ledger, in beautiful nineteenth century Spencerian script, are filled with the legal doings of a frontier Army outpost in the mid-late 1800s: court cases, marriage licenses, applications for citizenship.

Carter’s reign lasted until his death in1881. Oddly, he and Bridger, while having little in common on the face of it, were born in the same state, Virginia, and died in the same year. While building a road for the Army, Carter caught pleurisy on a stream—Carter Creek—named after him. He died at home in November of that year.

Written By

Eric Rossborough

Eric has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the McCracken Research Library. Eric comes here from Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.