I first met Harry Jackson when I was a seventh-grader in Mr. Gilpin’s art class. Because I grew up in Riverton, Wyoming, this inevitably meant a field trip up north to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody—especially if one was enrolled in any art or history class.

Okay, so I didn’t meet the artist “up close and personal.” I do remember, however, seeing his monumental, sequential paintings Stampede and Range Burial, in the Whitney Western Art Museum and being totally taken by their enormous size, some 10 feet high and 21 feet long. There were those intricate sculptures of each, too—“complex, but not complicated” as Harry would later say, a distinction he shared with me on numerous subjects. I stared and stared at them from every possible angle, trying to match up person-by-person and horse-by-horse to the paintings behind them. (The paintings are currently on loan to the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia.)

When I interviewed Harry in 2006, I was that sheepish seventh grader again with questions like: “Is it a stretch to make the leap from bronze to canvas?” “Do your eyes get tired painting something that big?” “Just how many steers are in that sculpture?” At this last question, he looked at me with a half-wince/half-grin and said, “Hell, I don’t know!”

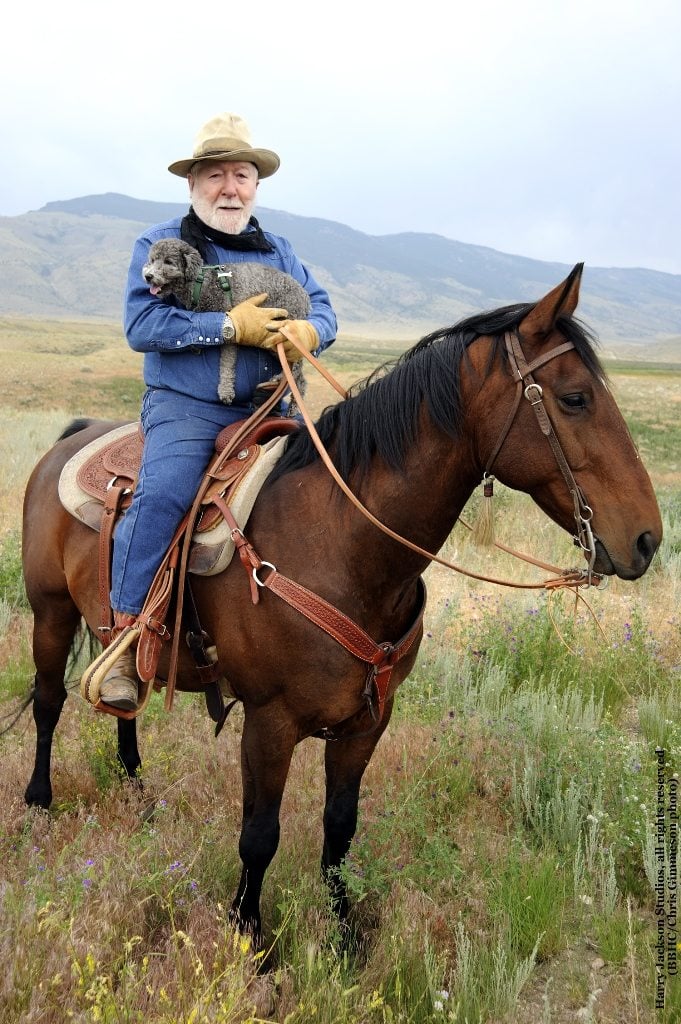

In chatting with Harry, it’s hard to imagine he wasn’t born a cowboy. He knew horses; the lion’s share of his artwork includes horses, cowboys, and Indians; he could “spin a yarn with the best of them”; and he actually was a saddle hand, especially at the legendary Pitchfork Ranch near Meeteetse, Wyoming, his “place of birth” according to his Marine discharge papers—not Chicago’s south side which was his true birthplace.

Harry shared a lifetime of stories behind the myriad of paintings and sculptures in his studio; then he waxed philosophical, as they say, about life and about art. “This is the way to look at any work of art, no matter how realistic or abstract it may be. Just let it happen to you,” Harry advised. Even though Harry was willing that I take away what ever I could from his work, I suppose I felt, on some level, unqualified to make that kind of judgment.

Our interview concluded, I looked over my notes and photocopies, and realized I could have written volumes more. A story about an artist as colorful as Harry Jackson is guaranteed to do that, I suppose. The writing brought me back, full-circle, however, to when I first caught sight of Harry’s Stampede during that seventh-grade art class visit.

And, that question about the number of longhorn steers in the sculpture? I counted them. There are 30.